CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

SOCIAL LABORATORY ON WEST SIDE STREETS CHICAGO SCHOOL OF PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY

Observers took notice that conventional metaphors which had framed an understanding of nineteenth-century cities seemed misplaced when applied to dynamo Chicago.

A romantic metaphor when cities evolved in natural, organic, and progressive steps from rural small towns and hamlets. The metaphor failed to account for major psychological disruptions and visual shocks for those suddenly immersed in a vast industrial smoky landscape. The initial experience of encounter with massive iron, steel, and brick works was jolting and disruptive–often eliciting unmentionable words.

A sunshine-shadow, day-night, light-dark metaphor of respectable law and order civilization competing on an upside/downside vertical line with barbarians who inhabited the shadow underground basements and sewers of the inner city. A majority of the population especially recent arrivals was now condemned to living within the bowels of darkness. A depraved, dangerous, and criminal cabal of devils hidden by a shadowy existence ruled at the core of the inner city.

A physics metaphor where numerical lines of force and fields of energy were represented by a draftsman’s design. Beyond the educated and professional classes, the one-dimensional metaphor convinced relatively few as they careered about in continual motion. City people played many roles hurrying about in every which direction, seldom realizing only intended consequences.

Chicago was the nation’s railway hub with its large corridors of yards, steel tracks, rolling stock, iron works, and warehouses streaming in and out from the center city. For natives of the Midwest, the sheer novelty of the experience when encountering the inland metropolis of Chicago seemed close to the very bone of existence.

The sardonic humorist Mark Twain (Missouri), laying over in Chicago during his continual travels, observed that it is “hopeless for the occasional visitor to try to keep up with Chicago–she outgrows his prophesies faster than he can make them. She is always a novelty; for she is never the Chicago you saw when you passed through the last time.”

The callow country boy Frank Lloyd Wright (Wisconsin) first arriving in Chicago at the Wells Street Station was stunned viscerally by the “harsh dissonance” and blinding blue-white glare of the arc lights everywhere, with the crowds “intent on seeing nothing.” He had never before seen an electric light. Signs “for this, that, and everything else”–saloons, food, eating places, bakeries, laundries, barber shops, tailors, dry goods–pressed against and claimed his eyes in a chaotic wilderness with a dozen strange languages. One paid a “heavy toll for being eye-minded” in the city. Chicago was “murderously actual.”

The greenhorn youth Hamlin Garland (Wisconsin) on his first train trip to Chicago professed, “I shall never forget the feeling of dismay … I perceived from the car window a huge smoke-cloud which embraced the whole eastern horizon … the soaring banner of the great and gloomy inland metropolis …. The train began to clatter through sooty freight yards filled with box cars and switching engines … after crawling through tangled, thickening webs of steel, it plunged into a huge, dark and noisy shed and came to a halt and a few moments later I faced the hackmen of Chicago.”

The aspiring reporter turned novelist Theodore Dreiser (Indiana) observed, “in 1889 Chicago had the peculiar qualifications of growth … which made of it a giant magnet drawing to itself from all quarters the hopeful and the hopeless …. It was a city of over 500,000 with the ambition, the daring, the activity of a metropolis of a million. It’s streets and houses were already scattered over an area of seventy-five square miles.” The city was a modern phenomenon.

- See Visitors on City Streets: Immigrant Emigrant City

- See West Side Habitat Urban Writers: Immigrant Emigrant City

Regional observations laid the groundwork for the emergence of a Chicago School of urban studies, the first American city to house an academic sociology built on foundations of empirical investigation to accumulate a body of knowledge for its own sake. Social workers and Hull-House residents drew on fact-based evidence, however their primary objective as reformers was not knowledge but active intervention in blighted neighborhoods to relieve hazardous conditions.

From the perspective of the emerging Chicago School, the inland city was a cultural, social, and psychological environment and “ecology” deserving of disciplinary knowledge unto itself. The on-site laboratory selected for empirical and eclectic study was neither the downtown nor the upscale neighborhoods but streets located on the territorial margins overflowing with alien immigrants and peoples of color first on the West Side.

An original essay published in German in 1903 by the theorist Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and the Mental Life,” highlighted the unique mental experience of a new phenomenon, the city person. It served to inform academics in the new Chicago project. Simmel’s Jewish origins in an era of Antisemitism made him a permanent outsider in a German professorial system favoring only race-qualified mandarins for civil service university positions. A sociological empiricist, eclectic critic, pluralist (not positivist), and essayist for general audiences, Simmel was in a unique position intellectually and socially to interpret the accelerating intensity and personal distancing occurring in the modern metropolitan experience.

The small town nurtured “feelings and emotional relationships” rooted in “the steady equilibrium” of familiar and enduring customs. In the metropolitan life the capitalist money economy required higher and impersonal “calculating” qualities associated with a heightened intensity of nervous energy and interpersonal conflict. Primary relationships between individuals were weakened in a cosmopolitan environment. Partial strangers functioned in complex systems in many roles to the end of a “highly diverse plurality of achievements.”

In the romantic footsteps of Nietzsche, preachers of high-minded “character” and triumphant individual greatness–the ubermensch or superman–hated the metropolis. It represented the center of a superficial individuality trivialized in a web belittling the great man. In contrast for Simmel, the metropolitan person adapted to circumstances, adjusted to mediating or functioning secondary institutions, and fashioned the results in forms of an impersonal “matter of factness.”

“Punctuality, calculability, and exactness, which are required by the complications and extensions of metropolitan life are not only most intimately connected with its capitalistic and intellectualistic character but also color the content of life and are conducive to the exclusion of those irrational, instinctive, sovereign traits and impulses which originally seek to determine the form of life.”

In the Chicago School of Sociology, the metropolis at the micro-level was an active agent in the heightened mental life of its inhabitants. Analysis, as in the following case studies by Charfles Bushnell, Nels Anderson, Louis Wirth, and William I. Thomas, was detailed and local. By way of criticism, politics relegated to a subordinate factor of social life tended to be neglected as was a positive role for traditional authority. bjb

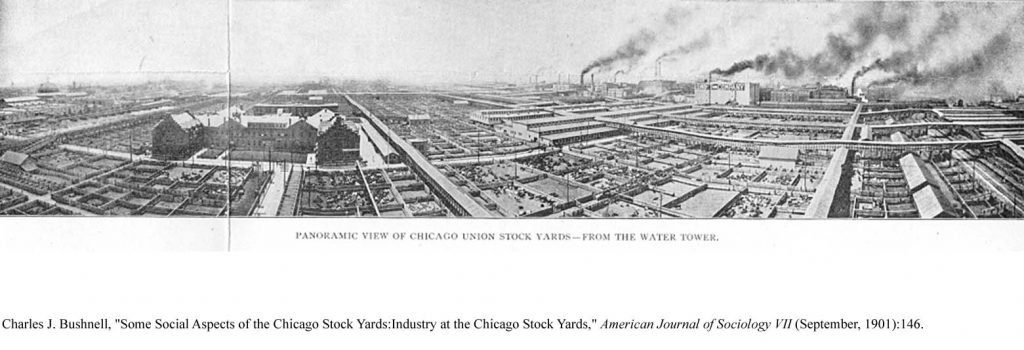

CHARLES BUSHNELL, CHICAGO STOCKYARDS (1901)

In 1901 Charles Bushnell published his three part dissertation study on the work processes and work environment at the Chicago Stockyards. He promoted the ethnographic use of photographs as an authoritative form of evidence not communicated by the conventional text, tables, and charts preferred by “experts.” Unequal gender relationships on the factory floor were now visually witnessed as were social costs to the neighborhood when children scavenged at the garbage dump and black soot polluted the air.

By means of enriching his text with the photographs, Bushnell censured management for its exploitation and neglect of the needs of workers. He took it for granted that the photographs communicated an intimate and immediate sense of the work, the social and neighborhood environments which narratives, descriptions, and tables did not adequately convey.

Bushnell’s innovative use of photography introduced what Lewis Hine at the end of the decade called “social photography” then later “photo story”–where images and text complement each other by contributing to a cognitive understanding of the subject. Hine was a graduate student in residence at the University of Chicago when Bushnell published his dissertation on the stockyards in the American Journal of Sociology, located at the University of Chicago. bjb

- 1 Chicago Stock Yards Industry

- 2 Chicago Stock Yards Community

- 3 Chicago Stock Yards Neighborhood

- 4 Chicago Stock Yards Industrial Democracy

- See American Journal of Sociology

STOCKYARDS: PHOTO GALLERY

SOCIOLOGISTS INVADE THE CITY, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO (1901-1929)

The keyword was “investigation.” The Sociology Department at the University of Chicago sent its graduate students on field trips into the marginal areas on the periphery of the rapidly expanding city–slums and industrial sectors–to investigate undesirable and deteriorating social conditions. Local residents could be less than welcoming to the relatively privileged college outsiders, characterizing them as on “slumming tours” with pencils, notebooks, and survey forms in hand. Nels Anderson, from a hobo family and an insider talking to residents in “Hobohemia” was an exception in the Department. The Chicago graduate students as well-to-do outsiders appeared to many locals as pests, a nuisance. Jane Addams became sufficiently concerned to respond that Settlement workers from Hull-House “do not do that sort of thing …. We never go into anyone’s house unless we have a good reason beyond a mere sociological reason. And we never go with notebook and pencil. Our visits are made as neighbors and friends.” bjb

- University Of Chicago Investigates City Social Condition (1901)

- University Of Chicago Tells How Stockyards Benefit The Cityl (1901)

- Ghetto Tires Of Invasion (1906)

- The Wail Of The Slums (1906)

- Maxwell Street: ‘We Got a Mad On The Census Man!’ (1910)

- Hobo Literati Will ‘Sub’ For U. of C. ‘Profs’ (1922)

- Hobos: How to Keep Well (1923)

- Chicago Ghetto Passing, is View of Sociologist (1928)

- U. of C. Will Conduct Survey To Help Negroes In Chicago (1929)

FRANK ADDISON MANNY: PROGRESSIVE EDUCATOR, JOHN DEWEY’S LABORATORY SCHOOL AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

A relatively obscure figure who deserves more attention from historians of Progressive education reforms, Frank Manny (1868-1954) was the operational right hand to the psychological theorizing by John Dewey at the University of Chicago. It was Manny who turned Dewey’s abstracted ideas into real world consequences.

In the 1890s with the group of students in the M.A. program around Dewey and an Assistant Professor of Pedagogy, Manny supervised the formation and working success of the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago. In addition, it was Manny who discovered the working class Lewis Hine, introduced him to Dewey, followed his progress as a graduate student at the University of Chicago, and hired him as a teached at Felix Adler’s progressive Ethical Culture School in New York.

- On Manny and Hine, See Origins of a Career in the Labor Conditions of an Industrial Hinterland City by Burton J. Bledstein

Manny was a Mid-westerner by birth and education, infected by neither the pretensions of Eastern status nor the entitlements claimed for credentials. Before following his primary passion to be an innovative educator, teacher trainer, and educational administrator, Manny had taught in a country school, coordinated the intricacies of a railroad freight department, and kept the books for a Land Company managing the first natural gas boom in the U.S.

Manny himself published a series of articles in professional education journals and magazines articulating the effective management of the student-centered classroom where students progressed in terms of their own development and immediate interests–not for “results” satisfying ambitious parents and pretentious social expectations. To advance the quality of teacher education, Manny focused on the unrealized potential of the State Normal Schools that universities were prepared only to supplement.

Holding high-profile positions in Midwestern high schools and a teachers college, Manny became with Dewey’s endorsement the go-to person in the field who everyone of importance knew could get things done. bjb

- High School Extension (1897)

- Recent Contributions To Moral Education (1902)

- School Management (1903)

- Education versus Business (1906)

- An English Experiment In Education (1907)

- Positive Function For School Museums (1907)

- Types of School Festivals (1907)

- German Contribution To Education For Vocation & Citizenship (1908)

- Recent Contribution To Moral Education (1908)

- The University Elementary School Curriculum (1908)

- A Problem For The Religious Education Association (1909)

- A Study In Adult Education (1909)

- American Schools Seen By a Belgian Educator (1909)

- Commission Form of Government and Public School System (1911)

JOHN DEWEY LETTERS TO FRANK MANNY (1896-1898)

- Dewey To Manny, May 10, 1896

- Dewey To Manny, June 20, 1896)

- Dewey To Manny, August 16, 1896

- Dewey To Manny, March 21, 1898

UNIVERSITY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: “DEWEY SCHOOL” (1905-1908)

- The University Elementary School: Its General Plan and Course of Study by Wilbur S. Jackman (1905)

- Mathematics And Its Relation To The Study of Home-Economics at The University Elementary School by Caroline May Peirce and Jenny H. Snow (1906)

- The University Elementary School (1907)

- The Course Of Study of The University Elementary School (1908)

- The University Elementary School Curriculum by Frank A. Manny (1908)

NELS ANDERSON, THE HOBO (1923)

Nels Anderson was born in Chicago in 1891. His father was an immigrant and qualified bricklayer and his mother from Swedish immigrant parentage. The family was Mormon and gave birth to twelve children. With the father’s trade in demand, the family followed the construction jobs traveling around the country. As Nels described it, he belonged to a migratory “hobo family” beating its way across the country always in need of making a self-sufficient living in a fluid economy

In 1901 the family returned to Chicago and settled in the vicinity of the “main stem” at Halsted and West Madison Streets. “We were slum dwellers, which I learned years later.” Money was tight, the family skilled at buying cheaply on the West Side. Hobohemia was home turf, a place of vivid boyhood memories. Nels plied the street trades befriending clerks in flophouses, friendly policemen, and prostitutes who paid him to run errands. (See his account in “The Mission Mill”).

After Chicago, Nels moved around as a transient laborer, served in the Army in WWI, did some college work at Brigham Young University in Utah. In 1921 at age 32 he returned to enter the M.A. program in Sociology at the University of Chicago, and supported himself as a full-time male nurse in an asylum.

Nels background was unique. A social class difference separated him as an outsider from the professors and students at the elite university. His chosen research topic was the Hobo, a scandalous topic among his peers. They assumed he must know other disreputable characters and would have a pernicious influence in the classroom, disqualifying him for recommendation to a teaching position.

Nel’s mentor Robert Park spent no more than fifteen minutes talking with him about the dissertation and asked no questions. An additional irritant to Park must have been that Nels professed no interest in becoming a “toady” of the current academic practices. He listened rather than took notes in class, and his “unscientific” methodology was to talk with residents in his comfort zone of Hobohemia, a technique later called “participant-observation.”

When Park declared his interest in publishing the M.A. thesis with the University Press, with no substantive changes, Nels laughed thinking it was not a publishable piece. Why Park recommended publication, beyond the reality that as general editor of the sociology series he needed a first publication, remains unclear. bjb

- 1. Hobohemia Defined

- 3. Homeless Man at Home

- 4. Getting By in Hobohemia

- 6. Types: Hobo and Tramp

- 7. Types: Home Guard and Bum

- 8. Types: Work

- See Hobohemia on West Madison Street

LOUIS WIRTH, THE GHETTO (1928)

Louis Wirth was born in Gemunden on the Maine, Germany, son of a relatively prosperous cattle-merchant and small-scale farmer, one of only twenty Jewish families in a village of nine hundred persons. Until age fourteen, Louis went to local schools operated by Protestant Evangelicals. He received extracurricular lessons in the basement of the synagogue from the local Rabbi and an itinerant Hebrew teacher. Very few youths from Gemunden matriculated to the academic level of a Gymnasium. In the meantime Louis’s three uncles had migrated to America. In 1911 one proposed bringing Louis with him to Omaha NE to attend public high school and receive a liberal education unavailable in the provincial ethnocentric Rhineland village.

Upon graduation from high school, Louis rejected the career in retail business planned for him by his family. In 1914, he entered the freshman class at the University of Chicago. In 1919 he graduated and began a career in social work as director of the division for delinquent boys for the Jewish Charities of Chicago. He married a non-Jew, the first in his family.

By means of his wife’s salary as a social worker, he returned to graduate school in Sociology at the University of Chicago in 1922. In 1924 he submitted a M.A.Thesis, “Cultural Conflicts in the Immigrant Family.” And in 1925 he completed a Ph.D. dissertation, “The Ghetto: A Study in Isolation.” In 1928 with no significant revisions beyond dropping the subtitle, he published the dissertation manuscript with the University of Chicago Press.

Generally speaking, Wirth was open-minded and pragmatic, skeptical at being harnessed to any particular theology, ideology, or dogmatism. His primary interest as a sociologist with a social work background centered on the novelty of human beings in historical, cultural, generational, and emotional transitions.

After New York and Warsaw, Jews in Chicago were the third largest concentration in the world with a difference, “a more diversified set of characteristics in its various parts than either of the other two.” In Chicago, Jews displayed more independent creative life and fewer persistent theological and intellectual othodoxies than in New York’s older and much larger ghetto .

In the new academic discipline of urban sociology, Chicago’s “ghetto” located at the intersection of Halsted and Maxwell in the slum of an industrial city was not usefully studied as a mirror-image of New York City’s Lower East Side. The latter was in many ways an old-world village “shtetl” dominated politically by centuries-old animosities between majority nationalities and defensive minorities.

The West Side of Chicago was “the most varied assortment of people to be found in any similar area of the world.” It presented a real-life laboratory containing adversarial immigrant and race colonies, None held a majority or remained in the same place more than one generation or so before moving to second and third settlement residential areas in the city and suburbs.

Wirth was attentive to social processes of assimilation, adaptation, and inclusion. He observed for example that in a little more than one generation on Chicago’s West Side,“the Poles and the Jews,” sworn and hateful enemies in their native land, continue “to detest each other thoroughly” but they now “trade with each other very successfully.”

Antisemitism persisted as a menacing presence and barbaric reality in the Polish homelands. In the U.S. and Chicago, Wirth emphasized successful institutional activities like the Anti-Defamation League and organized responses to Henry Ford and the modern Ku Klux Klan to contain periodic outbursts of hate.

The invasion of the West-Side ghetto by the Negro, segregated racially by the white landlords in greater Chicago, became “of more than passing interest.” Jews, Wirth observed, settled in the area “precisely for the same reason” as the Negro, and presented no “appreciable resistance” to their presence. Contrary to more antagonistic ethnic nationalities in the area, “Jewish immigrants in the ghetto have not as yet discovered the colored line.”

Why not? In an economic environment where one price did not fit all, seller and buyer successfully exchanged goods and services with an urban solvent that knew only one color. “The Negroes pay good rent and spend their money readily.” In the context of sharp cultural differences, U.S. coin was a common denominator. Coin from Anglo hands had no more value than from Irish, Italian, or Greek hands. Good business was good relationships. Wirth overstated his positive case on race congeniality, nevertheless his observation drew useful perspectives on commercial prosperity and the role played in ghetto markets by suborned Negro labor.

Albeit a small world with a depth of emotion, Wirth’s Ghetto in Chicago was an historically dynamic institution with irreversible changes occurring over time and place in the lives of successive generations of families and individuals. The publication formalized a concept of a local place including the economy, religion, cultural mores, politics, and generational adaptations and assimilation. All these themes continue to be borrowed, explored, adapted, and re-interpreted by urban, ethnic, and minority historians and sociologists to this day. bjb

- Forward

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: The Origin of The Ghetto: Seeking New Homes

- Chapter 3: The Ghetto Becomes an Institution: The Compulsory Ghetto

- Chapter 4: Frankfort a Typical Ghetto: Historical Aspects

- Chapter 5: The Jewish Type: The Jews as a Race

- Chapter 6: The Jewish Mind: Mentality and the Division of Labor

- Chapter 7: The Ghetto in Dissolution: Social Movements

- Chapter 8: Jews in America First Settlers: The Sephardim

- Chapter 9: Origins of the Jewish Community in Chicago: The Pioneers

- Chapter 10: The Jewish Community and the Ghetto: The Growth of the Community

- Chapter 11: The Chicago Ghetto: The Near West Side

- Chapter 12: The Vanishing Ghetto: The Flight From The Ghetto

- Chapter 13: The Return to The Ghetto: Conflict and Self-Consciousness

- Chapter 14: The Sociological Significance of the Ghetto: Non-Jewish Ghettos

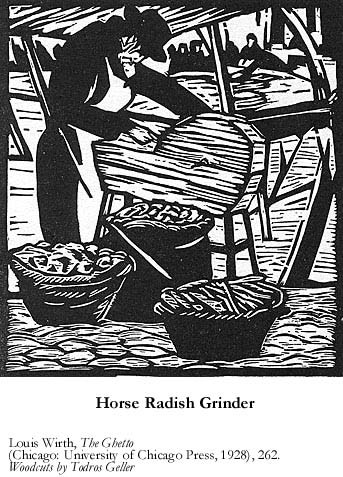

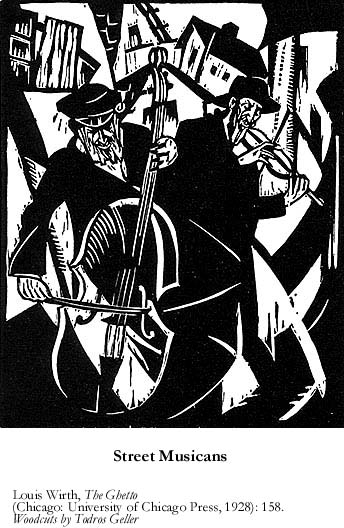

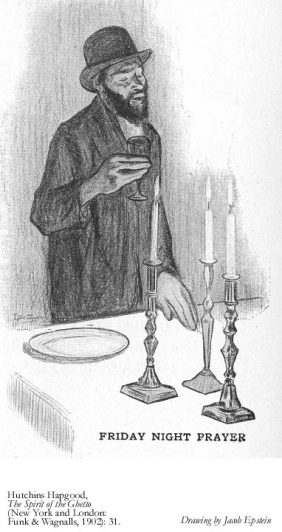

GALLERY THE GHETTO: WOODCUTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

The quaint and picturesque woodcut illustrations in Wirth’s text convey the old-world sectarian and provincial spirit of orthodox types in the village Stetl of mythic memory. Wirth neither acknowledged the woodcuts nor the name of the artist in his introductory credits. Almost certainly, Wirth’s mentor and the Anglo editor at the press made the decision to upgrade the publishing values of the book with artistic images separating chapters. The quaint and picturesque woodcuts resembled Joseph Epstein’s celebrated illustrations of old-world character types which adorned Hutchins Hapgood, The Spirit of the Ghetto: Studies of the Jewish Quarter of New York (1902)

A selection of contemporary photographs by the editor would have been a more suitable representation of Wirth’s text and historical discussion of the evolution of the modern urban “ghetto,” a port in the industrial city for recent arrivals to neighborhoods on the margin. bjb

- Todros Geller Woodcuts in Louis Wirth, The Ghetto (1928)

- Joseph Epstein Illustrations in Hutchins Hapgood, The Spirit of the Ghetto (1902)

- See Louis Wirth Sociologist Ghetto Living

PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIAL PRACTICE (1884-1913)

“Some universities have plenty of thought to show but no school,” wrote William James about Psychology departments in 1905, “others plenty of school but no thought. The University of Chicago … shows real thought and a real school.” High praise from the dean of a radical pragmatic psychology of conscious behavior rooted in personal historical “experience” and grounded in empirical observation. In this new conceptual approach from the perspective of an active participant, there were neither discernible Absolutes nor elemental truths. The steady streams of circumstances in a psychological life were relative. The flow of time passed relentlessly in a temporal world of social “situations” with unintended consequences. When the conventions of the fly-wheel of “habit” failed an individual, “reconstruction” of attitudes and points of view became necessary.

From the perspective of Social Psychology, “truth” happened to a mental idea in a “situation.” Neither inherent nor essential, credibility or truth occurred after an active process of social experimentation, individual interaction, comparative testing, logical reasoning, and trial interventions. Canonical high priests of evolutionary biology and genetically determined racial characteristics misstated the plural and layered realities in an historical individual’s life .

John Dewey proposed reconstructing the schoolroom and the curriculum by placing the student not the teacher or superficial “status demands” at the center of progressive learning. In response to a Cartesian “Man Machine” he argued in the “New Psychology” that “man is somewhat more than a neatly dovetailed psychical machine who may be taken as an isolated individual, laid on the dissecting table of analysis and duly anatomized.” Unlike the medical analogy of a forensic autopsy to determine physical causation, W.I. Thomas concluded that the province of Social Psychology “is the examination of the interaction of individual consciousness and society, and the effect of the interaction on individual consciousness on the one hand and on society on the other.” bjb

- The New Psychology by John Dewey (1884)

- Working Hypothesis In Social Reform by George Herbert Mead (1899)

- Psychology And Social Practice by John Dewey (1900)

- The School As Social Center by John Dewey (1902)

- The Chicago School by William James (1904)

- The Province Of Social Psychology by William I. Thomas (1905)

- What Social Objects Must Psychology Presuppose by George Herbert Mead (1910)

- Social Phases Of Psychology by George Stanley Hall (1913)

SOCIOLOGY AND THE URBAN HABIT OF MIND: H.B. WOOLSTON AND ROBERT E. PARK (1912-1923)

In the “Urban Habit of Mind” H.B. Woolston argued that modern industrial cities like Chicago were qualitatively different from small towns in the agricultural countryside. The urban environment was visually distinctive: bellowing smoke stacks, red glowing steam from mills, masses of pedestrians on the streets, stately department stores as centers of consumption. Urban labor markets attracted thousands of young men and women ambitious to make their fortune.

Moreover, in contrast to rural living, close personal contact in the industrial cities greatly multiplied the need to react to variety, swift movement, and progress. The general state of “nervousness” now intensified. Citing Georg Simmel, Woolston agreed that people in cities were compelled to immerse themselves in the quantifiable and objectified money-centered “social economy” unlike that found in their secluded provinces of origin. With the recent mobility of large and diverse populations, “urban selection” in Chicago came in for specific recognition:

“Under the demands of a great labor market, the cheapest or the most efficient workers secure the jobs. Some years ago the newsboys down town in Chicago were hard-hitting Irish lads. Gradually industrious Jewish boys, who were on their corner early, rain or shine, edged out their more erratic competitors. More recently the Italian, who is both a fighter and a stayer, pushed his way into the business.’ The same process of displacement has taken place in the clothing trades and construction work. In the former, Hebrews have superseded Germans, in the latter, Italian laborers are pressing hard on the Irish. In many lines, wider competition leads to a more severe economic struggle. Greek bootblacks, French cooks, and German correspondence clerks now appear to survive in this process of urban selection. Under the intensified pressure, racial and national prejudice gives way to tests of capacity.”

Raised in the Midwest, Robert E. Park served as a beat-reporter for ten years before pursuing graduate study in psychology and philosophy at Harvard with William James. Park’s dissertation explored the contrasts in urban settings between unruly “crowds” and mobs provoked instinctively by mass suggestion on the one hand and the realm of “public” composed of individuals with different opinions and guided by prudent and rational reflection on the other.

Park then worked ten years as a publicist and ghost writer for Booker T. Washington. At a Tuskegee Conference around 1913 he met William I. Thomas who invited him to teach classes at the University of Chicago. A reporter by vocation, Park encouraged students to rove around Chicago and place in historical context caricatured urban stereotypes such as gangs, hobos and delinquents. He grounded his academic sociology in “process” not “structure,” experience and “attitude”–not biological “instinct.”

“The City,” his widely-read essay in 1915, presented urban spheres where questions about the break- down of primary group intimate attachments replaced by casual fortuitous city relationships called out for ethnographic investigation by students. Park’s vision of Chicago became a pluralist “mosaic” of idiosyncratic worlds, touching but not interpenetrating, each category an atypical unstable world in its own right: neighborhoods, colonies, segregated areas, vocational types, secondary institutions. Seen one–slum, ghetto, criminal gang, family–not possible to have seen the divergence and diversity in them all in a pluralist universe!

City life was incongruous and asymmetrical, not surreal in a science fiction alternate world. City people who “meet and mingle together … never fully comprehend one another.” Anarchist and club man, priest and Levite (Jew), actor and missionary touch elbows on the street, then go their way. Relevant to context, they play multiple roles. Passing from one milieu to another, living simultaneously in contiguous but separated worlds, permitted plural even conflicting identities–”eccentricities”–not found in the timeless familiarity of an isolated small town.

Inspired by Georg Simmel’s theorizing, Park characterized the city as a “fascinating but dangerous experiment” where “divergent types” found a milieu in which to flourish, for good and ill. Social relationships were now complicated by an “element of chance and adventure which adds to the stimulus of city life and gives it for young and fresh nerves …. a superficial and adventitious character.”

Park’s asked a fundamental urban question. Which organized and stable “institutional” forms–sport, play, art, vocations, for instance–would both permit expression of the range of human passions and appetites and also impose a socializing discipline to produce a functional “public” civilization?

Later in the 1920s, Park coined the term “human ecology” (from natural science), and with Earnest Burgess graphically drew concentric rings of zones on a city map with areas of deterioration and decay (the West Side) circling the downtown with more prosperous suburbs at the outer edge. bjb

- The City as a Socializing Agency: The Physical Basis of the City: The City Plan by Frederic C. Howe (1912)

- The Urban Habit of Mind by H.B. Woolston (1912)

- The City: Suggestions for the Investigation of Human Behavior in the City Environment by Robert E. Park (1915)

- The Social Survey: a Field for Constructive Service by Departments of Sociology by Ernest W. Burgess (1916)

- Old World Traits Transplanted by Robert E. Park, Herbert Adolphus Miller (1921)

- Interdependence of Sociology and Social Work by Ernest W. Burgess (1923)

- The Study Of The Delinquent As a Person by Ernest W. Burgess (1923)

WILLIAM I. THOMAS ON CULTURAL ATTITUDE AND SOCIAL PERSONALITY (1901-1923)

William I. Thomas was a complicated man trained in his early years in the humanities and languages. In the 1890s, when he came to the University of Chicago Department of Sociology, he had arrived at an understanding of the influence on conduct of cultural expectations and the social dimensions of personality. “Attitude” and “situational” awareness were primary building blocks of a new discipline based on documentary observation of individual cases, idiosyncratic experience, and personal recollection. The relevance of sociology was more akin to perspectival subjectivity in psychology and history than to positivist objectivity in the physical and biological sciences. Thomas was too sophisticated to accept a value-judgment approach which perceived social change as inevitably producing impersonalism and disorganization.

Not dissimilar to Thorstein Veblen, his rebellious colleague at the University of Chicago, Thomas took satisfaction both personally and intellectually by going against the grain of university administrators and faculty striving for genteel respectability. Thomas was a prolific essayist on publicly controversial topics such as women, sex, marriage, dress, gamesters, eugenics, and female suffrage. Witness to the imperialistic Spanish-American War and the ascendance of a militaristic aggressive Theodore Roosevelt, he observed that manifestations of the emotional excitement of risk-taking, the contest, gambling, and the competitive spirit in organized sports and capitalist business persisted as powerfully in modern cultural attitudes as in “primitive.”

Thomas’s magnum opus with Florian Znaniecki , The Polish Peasant in Europe and America: Monograph of an Immigrant Group (5 Vols., 1918-1920) was described as “probably the single most important work establishing sociology as a discipline in America.” In part, the project developed from his personal encounters with Hull-House residents and locals on the streets of the West Side neighborhood. bjb

- The Gaming Instinct by William I. Thomas (1901)

- The Psychology Of Race Prejudice by William I. Thomas (1904)

- The Province Of Social Psychology by William I. Thomas (1905)

- Standpoint for the Interpretation Of Savage Society by William I. Thomas (1909)

- The Polish Peasant In Europe & America V.5 by William I. Thomas (1920)

- The Unadjusted Girl by William I. Thomas (1923)