CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

19th-CENTURY CAMERA

The popularity of photography in nineteenth-century American life grew rapidly after the first daguerreotype portraits appeared in the 1840s. ‘49ers coming off the Overland Trail into the California Mother Lode gold fields routinely patronized daguerreotype “artists” in field shacks for a likeness of their new Western masculine identities, including thick beards, unshorn hair, flannel shirts, heavy-duty coveralls, miner’s tools, weapons at the ready. These “poor man” portraits were mailed to family members who remained at home back East, anxious about the fortune and fate of their husbands, sons and brothers.

The panoramic cityscapes by daguerreotypists of San Francisco in the Gold Rush period were the first of its kind for an American city, unlike the relatively few street views of home fronts and business establishments in older American cities like Boston and New York A substantial number of photographers initially were attracted to California by the adventure of gold. At $5.00 a sitting, and high demand, they soon realized that practicing their daguerreotype craft was more lucrative, reliable, and rewarding than the dirty, speculative, and seasonable job of digging. Daguerreotyping in its first decades was a commercial indoor studio portrait art with its familiar props and rigid poses.

Unlike older Eastern cities, San Francisco flourished as an instant city on the scenic west coast. Its deep-water harbor, packed with ships, became a port of entry for the booming commercial business necessary to supply the material needs and many services required by the geographically expansive “mother lode” region. The rapid appearance of city streets rising on the steep hilly terrain upward from the crowded harbor, and scenery of bustling prosperity and advancing civilization sent the indoor studio daguerreotypists outdoors for innovative perspectives.

They now visualized the panoramic cityscapes of this new flourishing civilization propelled to immediate success rising on the vertically inclined hill sides.

Among the more bizarre and disturbing uses of early photography in the mid-nineteenth century were post-mortem portraits mourning the dead. Death haunted the commonplace where people lived–at home. Especially vulnerable infants and children in precarious health died in high numbers prior to successful medical science interventions. An inexpensive photograph ministered a permanent solace and a living memory of the innocent departed pictured within the intimate “family circle.” Posed for the camera, often propped up by surviving siblings and parents, the dead now appeared to be sleeping peacefully, almost alive, and forever present in your thoughts of a better place.

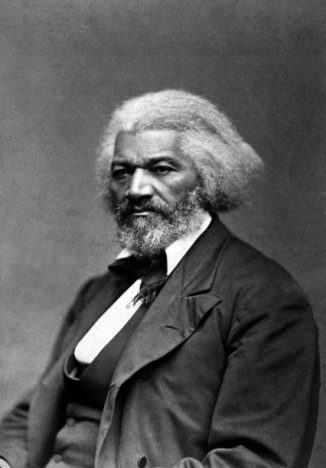

By the 1860s, photographs surpassed all forms of print. Former slave Frederick Douglass became the most frequently photographed American in the nineteenth-century. He argued in written lectures that with the the progress made by the innovative appearance of the photograph, a “great want” for a positive African-American race identity was now a reality. “The humblest servant girl, whose income is but a few shillings per week, may now possess a more perfect likeness of herself than noble ladies and even royalty, with all its precious treasures could purchase fifty years ago.” In studied detail, Douglass’s personal features from a serious young man who wrote Narrative of a Life (1845) to the severe appearance of a post-Civil War national leader of his race projected the gravity of a life committed to opposing demeaning stereotypes of shuffling slaves.

Civil War recruits and draftees ceremoniously visited a photographer’s studio dressed in uniform before embarking for camp, leaving behind a lasting youthful memory on the mantles of parents and family. Many never returned. Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War (1865-1866) framed the “harvest of death” over four bloody years of war. Pictorial magazines such as Harper’s Weekly graphically illustrated heroic charges across the ground of battlefields. In Gardner and Bradley photographs heroism was not to be found in the slaughter of war. The field photographer gazed morbidly on the ditches and trenches strewn with disfigured corpses after a battle. “Verbal representations of such places, or scenes, may or may not have the merit of accuracy,” Gardner insisted, “but photographic presentments of them will be accepted by posterity with an undoubting faith.”

Photographic images, often redrawn by lithographic artists, began routinely appearing in nineteenth century magazines, guide-books, and advertisements. Many who migrated to Chicago in this period, for instance, had seen a scene of the city in a picture book before actually seeing it with their own eyes. Some later wondered, which viewing had come first.

A proliferation of photo studios on city streets sprung up specializing in individual and family events at affordable prices. Disposable income was rising in the later nineteenth century. The purchase of stereoscopes to view Western landscapes, Carte de visite portraits for insertion in letters and visitation announcements, picture trade cards and postcards including postcards of lynchings, and an “indecent” stereoscope pornography “peep” show on the Midway at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair–all multiplied exponentially.

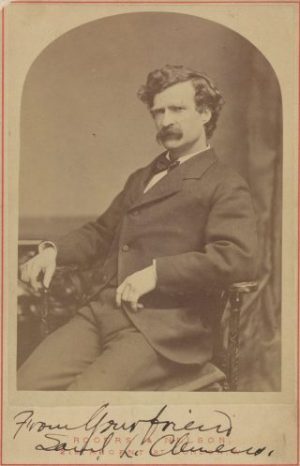

Mark Twain included his Carte de visite photograph within the thousands of letters he wrote and distributed. He became among the most publicly recognized and instantly identified persons in the later nineteenth-century, a latter-day Ben Franklin. Never missing a beat to cash in, Twain saw his opportunity in favorable branding circumstances. His image and endorsement appeared on multiple advertisements from scrapbooks to soaps for linens.

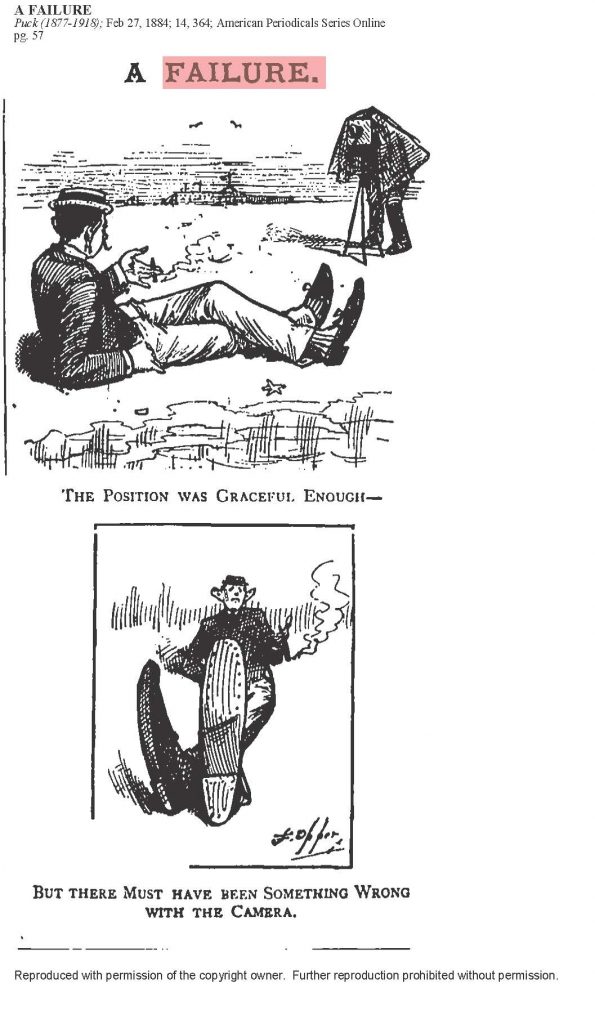

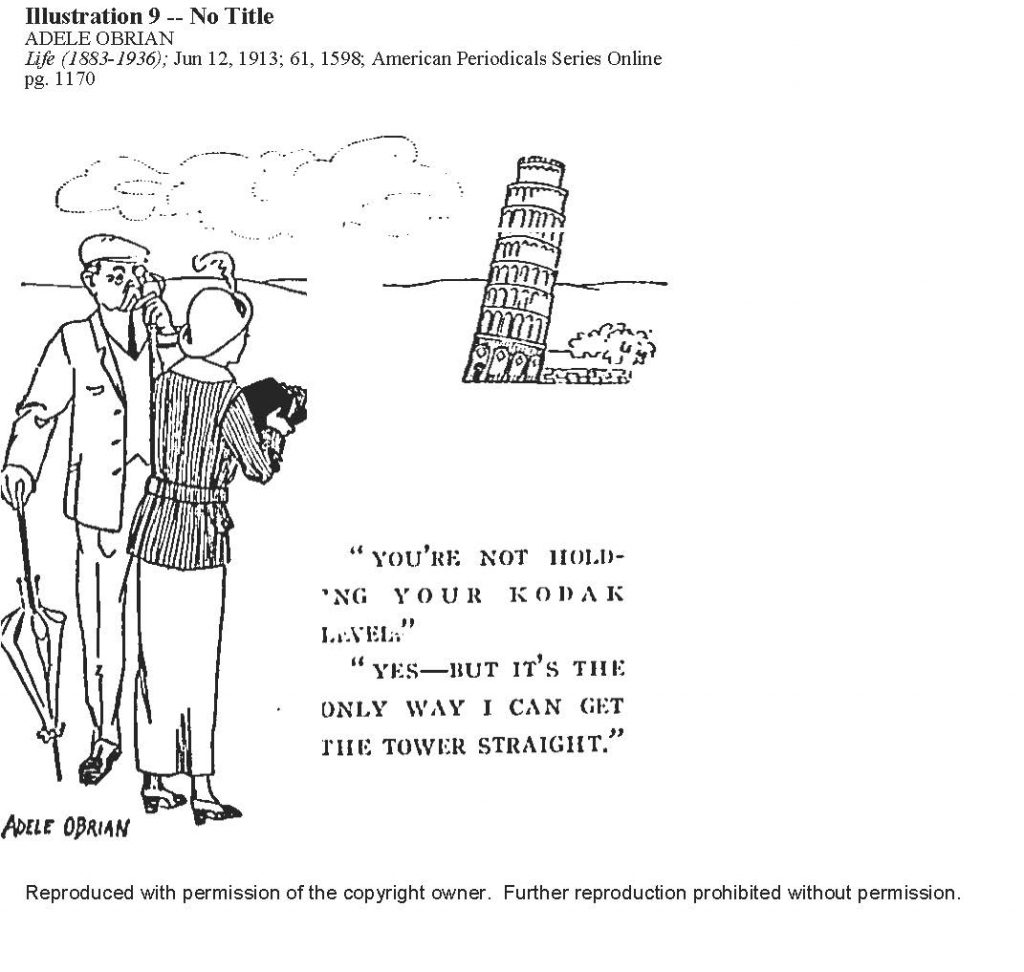

A keen amateur interest in photography escalated with the appearance of Eastman Kodak’s portable Brownie camera priced for popular distribution ($1.00) and ease of use. The “button-pressing” amateur photographer became Kodak’s primary mass market. The heavily advertised corporate slogan “You Press the Button, We do the Rest” had global reach, with the emphasis, “We do the Rest.”

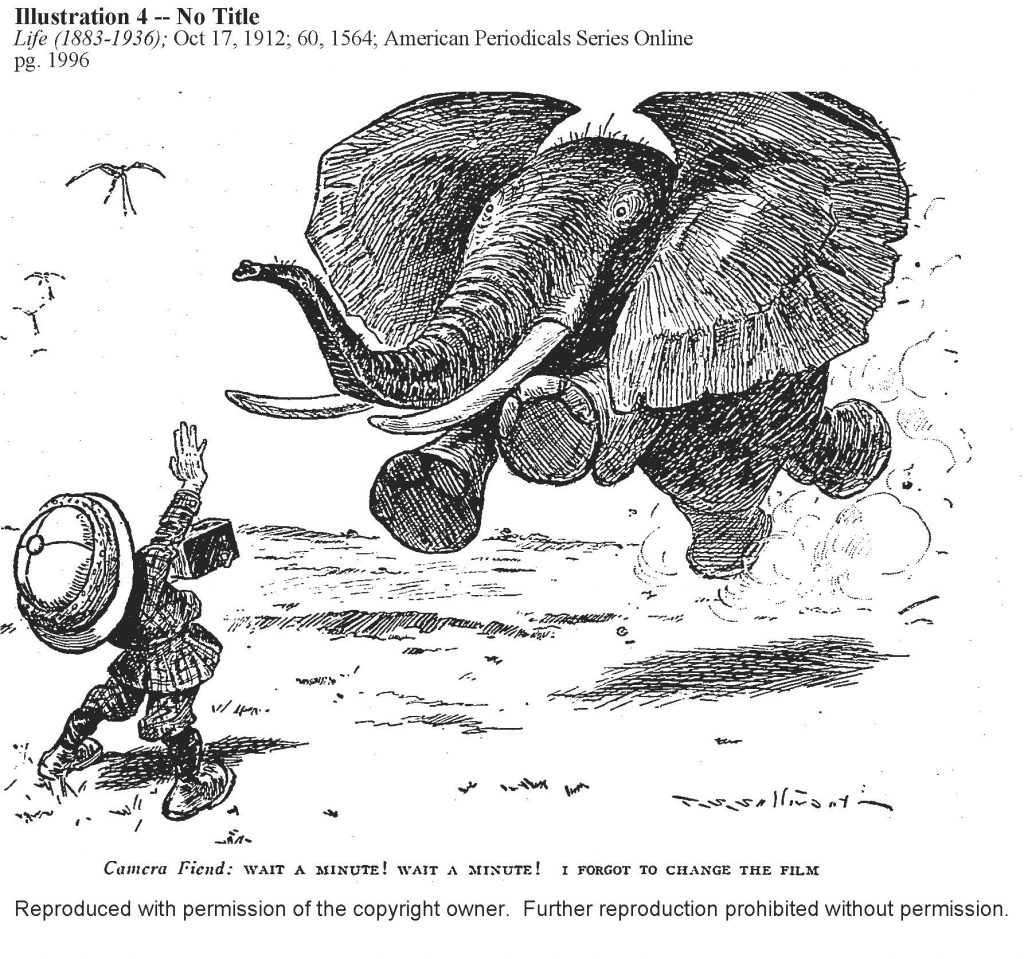

The 18th century voyeur or “Peeping Tom” was reincarnated in the early 20th century prying “Kodak fiend” and “camera fiend.” A peeper with a “detective camera” could snoop around dark corners exposing the hidden lives of celebrities and cheats. An emerging profession of hired private investigators embraced the new tool with its capacity for stealth and power to invade private spaces. Judicial courts were now accepting photographs as evidence in divorce and abuse cases.

“Snapshot” or a mental and visual “survey” of a slice of reality quickly became an everyday figure of U.S. speech representing a new take on social knowledge. For instance, promoted in Field and Stream magazines the Kodak became the “weapon of choice” of hunting clubs formed nationally,“There are no game laws for those who hunt with a Kodak.” When the “trigger” was squeezed a camera attached to a rifle “snapped” an instant “shot” of an animal scene in the rough.

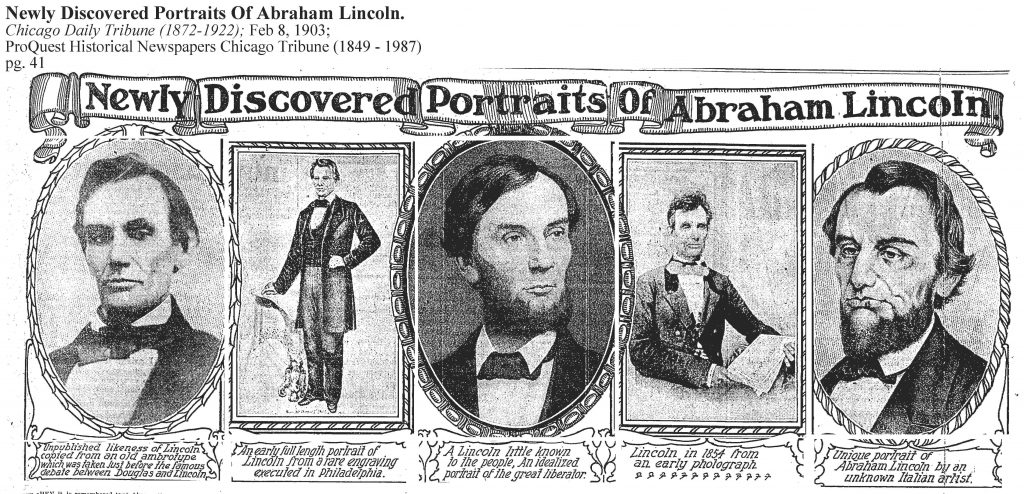

Innovative half-tone technologies made for a cost effective production of photographs on cheap newsprint . Photojournalists at newspapers such as the Chicago Daily Tribune and the Chicago Daily News began building photo archives which editors used to enhance and intensify the reader experience, and expand the audience in competitive markets. In 1903 the Daily Tribune displayed newly discovered photographs of Abraham Lincoln. In 1905 the Daily News photographers pictured pitched confrontations on local streets between hostile ethnic and racial groups during the Chicago Stockyard strike.

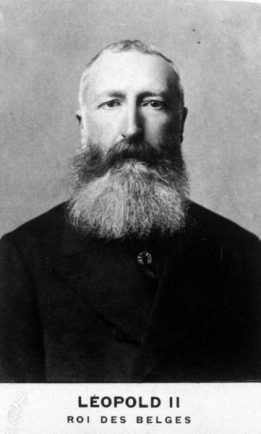

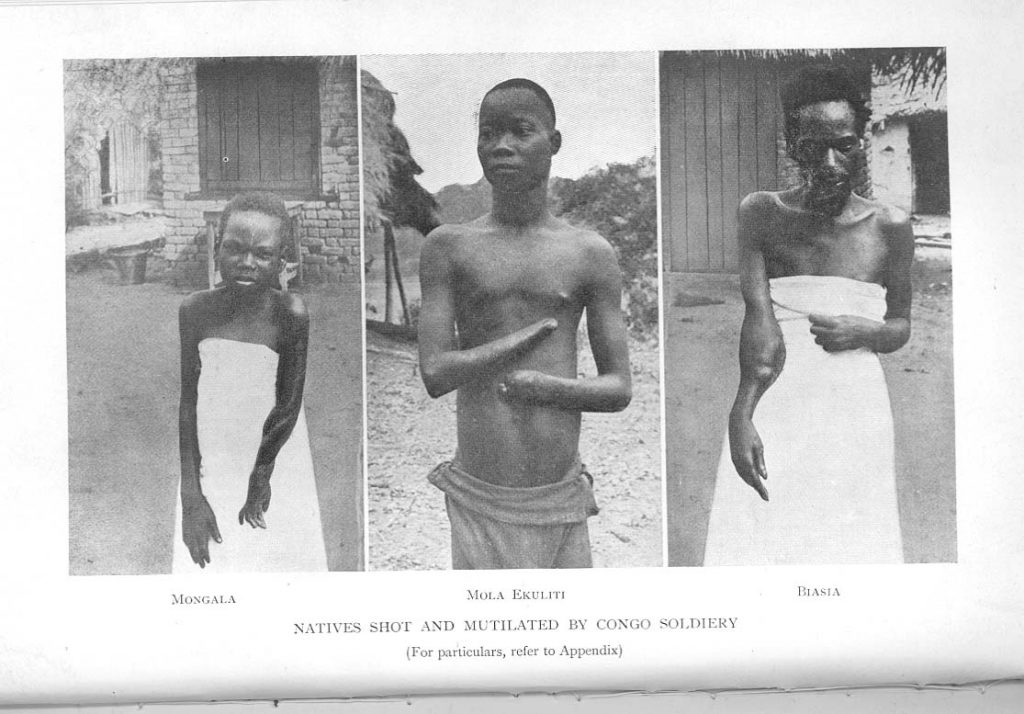

What a phenomenon looked like from the visual perspective of a photograph began to make a difference in how readers fixed on the indelible features of a story. In 1904 E. D. Morel, a British journalist and abolitionist active in the Congo Reform Association, pictured with a Kodak native rubber workers in King Leopold’s Congo, a Belgium colony in Africa. The King promoted the colony for its “civilizing” example of Empire supplying a necessary raw material to advanced Western economies. Theodore Roosevelt numbered among the King’s admirers.

Inside the “heart of darkness,” Congo enforcers boasted of collecting hundreds of amputated hands and limbs as trophies during Leopold’s military campaigns against the enslaved native workers in the countryside. Morel’s collection of missionary Kodak images of mutilated workers with hands chopped off and severed limbs by Leopold’s thugs documented the perversity of the horror. The display of the atrocity highlighting native misery was a visual refutation beyond words of the nineteenth-century liberal celebration of peaceful harmony and enlightened progress among nations.

In his anti-imperialism manuscript, King Leopold’s Soliloquy (1906), Mark Twain had the king speak in a manic outburst to the “only witness I could not bribe”–the incorruptible Kodak. “The Kodak has been a sole calamity to us …. In the early years we had no trouble in getting the press to ‘expose’ the tales of mutilations as slanders, lies, inventions of busy-body American missionaries and exasperated foreigners.” With Morel’s Kodaks now in the public domain “all harmony went to hell.”

Also in 1906 the overwhelming devastation caused by the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire was reported daily in the national press featuring current photographs. In contrast to the public’s familiarity with depictions of natural disasters, the San Francisco imagery disclosed the incredible magnitude of a man-made disaster in a city built by and for money interests. bjb