CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

SOUTH WATER STREET MARKET

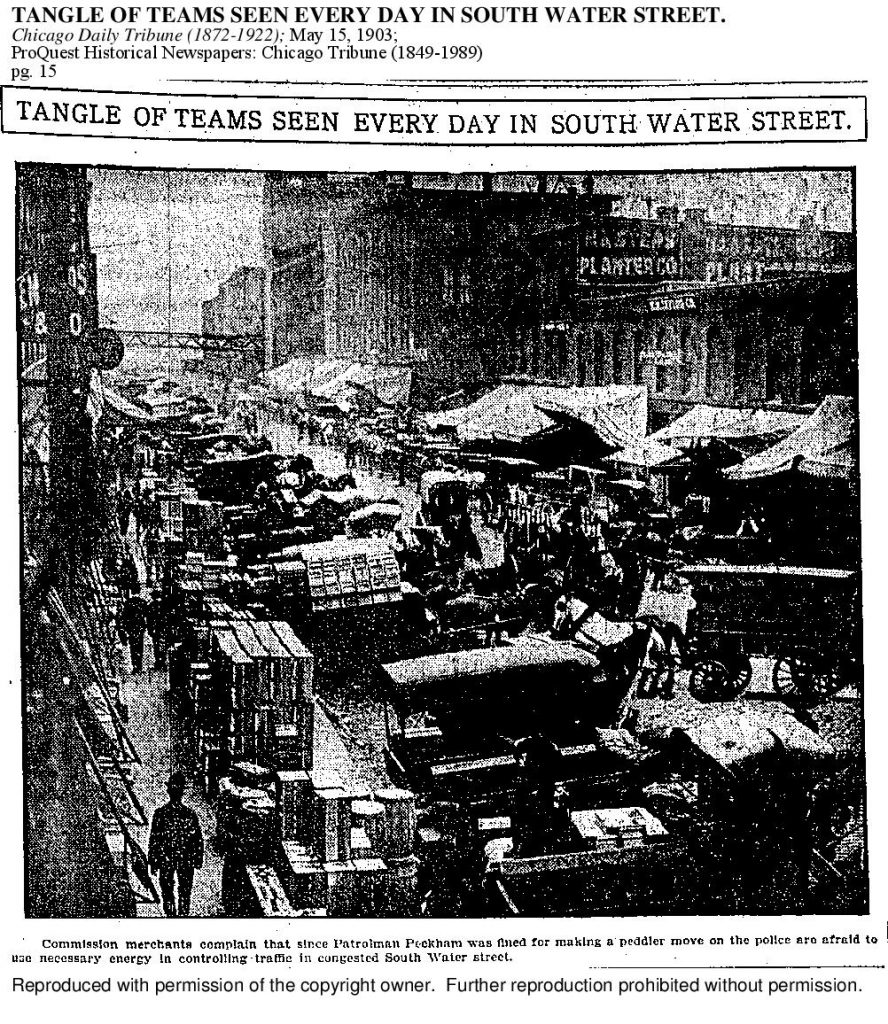

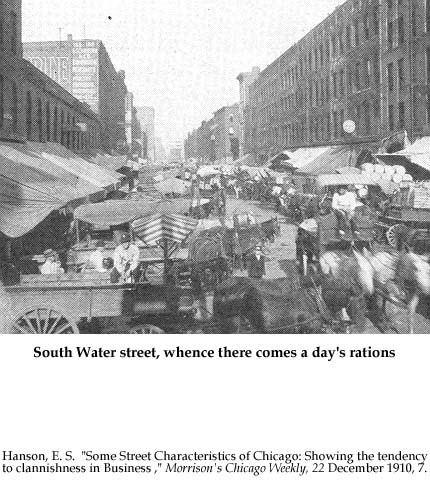

South Water Street was the city’s wholesale produce market originally located on the south side of the Chicago River’s main branch. When the downtown Loop was upscaled to serve as a financial and retail center for the Midwest region, city planners (encouraged by the Burnham’s Plan of Chicago) lobbied to move the market to a distant place–a district where horse manure on the streets and rotting produce would not contradict the city’s promotional self-image of a high “civilization” noted for premier museums, sculpted gardens, and “city beautiful” parks.

South Water Street kept its name when it relocated in 1925 to West Side streets bounded by 14th St. Place just south of Maxwell Street and the 16th St. Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal rail embankment. It became the largest produce market by area in the nation. Also it was among the busiest within eight square blocks of concrete buildings, 166 wholesale stalls and commission houses. The market warehoused and distributed daily produce and food products to neighborhood markets, restaurants, and city residents. And from its central geographic location in the upper Midwest it distributed perishable commodities to markets in regional cities like Milwaukee.

From very early morning the produce market was clogged with vehicles and foot traffic. The atmosphere was one of constant noise, uproar, and immediate confusion. Daily truck farmers brought in their crates of local fresh fruits. vegetables, and poultry products which were then auctioned off to the multiple factors supplying waiting vendors. The city daily consumed a vast quantity of foodstuffs at seasonable prices from the Water Street Market. Only later did mass-market major retail supermarket chain warehouses appear. A busy and profitable South Water Market continued to serve neighborhood groceries, restaurants, and local vendors.

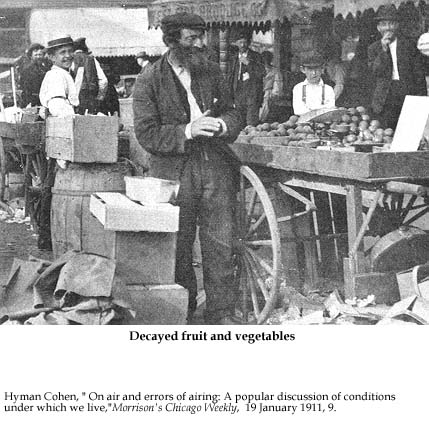

As the documents from the first Water Street Market location at the north end of the Loop reveal, relationships between teamsters, landlords, merchants, peddlers, and foot consumers were contentious and loud. These agents were not passive, State Street decorum was not the standard. At issue was the quality of perishable goods. Setting a competitive price by selling off surplus perishable inventory was necessary to stay in business–even at break-even cost with no profit to the seller.

Among the beneficiaries of this system of distribution were consumers on budgets, especially housewives and families. In good years they could buy at prices “so low none need go without the best.” Profiting from the bounty homemakers could take advantage of the inexpensive Mason Jar for home canning. First patented in 1858, the Mason Jar was a successful food technology requiring only a special glass jar and boiling water. A bumper crop of Michigan or Indiana peaches, for instance, became a year-round nutritional bonanza for a family’s quality of life and budget.

Indeed, there were no food riots due to high costs or scarcity in Chicago. Nor were there vocal complaints of “food deserts” in working and lower class neighborhoods in the West Side ghetto and slum. bjb

PHOTO GALLERY

BUSINESS-LABOR RELATIONS IN THE MARKET (1890-1910)

- Declaring Their Worth (1890)

- They Threaten To Move, Against High Rents (1890)

- Why They Cling To South Water Street (1890)

- Where Business Room Cost Money (1895)

- Among South Water Street Hustlers (1901)

- Decline To Haul Produce (1902)

- Commission Men Face Strike (1903)

- Injures City As Market, Strike Conditions (1905)

- Drivers Mean To Strike, Labor War (1906)

- Peddlers Openly Charge Bribery (1908)

- South Water Street Busy-20,000 Vehicles in One Day (1910)

HOUSEWIFE’S ECONOMY (1890-1914)

- Bananas by Fast Train (1890)

- Good Things For Dinner (1890)

- On South Water Street (1892)

- Fruit Plenty And Cheap (1896)

- Market Lists For The Housewives (1896)

- Tangles of Teams Seen Every Day on South Water Street (1903)

- Food of Chicago Brought to City as People Sleep (1914)

PERISHABLE PRODUCE (1882-1914)

- Market Matters, A Generally Prosperous Condition (1882)

- The Marketing Problem, Why It is Cheaper to do it on South Water Street (1884)

- South Water Street Market, The Articles On Sale and the Prices Asked for them (1888)

- Latest Articles in the Market, What South Water Street Has To Offer, the Prices (1888)

- For a Produce Market, A New Ten-Story Building to Cover a Whole West Side Block (1890)

- To Excel All Other Markets (1890)

- Where Business Room Costs Money (1895)

- South Water Street (1906)

- South Water Denies “Trust” Charge (1909)