CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

RUSSIAN HEBREWS: MAXWELL STREET

Named for a physician, Philip Maxwell, who settled and died in Chicago in 1859, the Maxwell Street area was among the oldest in Chicago. Located on the eastern side at the south branch of the Chicago River with a few industrial buildings, the street moved westward with increasing residential density around Jefferson Street, where outdoor marketing first appeared. In the 1850s the area became a port of entry for immigrants, initially Irish and German, living both in small wood cottages begrimed in soot and in two to three story clapboard buildings falling to pieces, on streets that were quagmires of black mud, rotten planks, and miserable lighting.

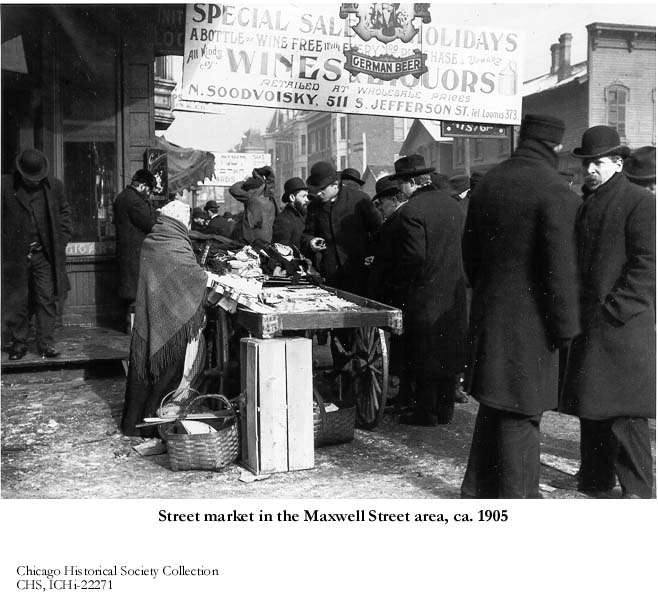

In the 1870 and 1880 period, Russian Jewish immigrants began to replace the Irish. As the most densely populated neighborhood in Chicago, an area known as the Maxwell Street District now extended from 16th Street on the south and Polk Street on the north and the Chicago River and Halsted Street on the east and west. The focal point was the intersection of Halsted and 13th Street named Maxwell. Storefronts and a trolley line fronted on 13th Street. Pushcarts now spilled from the north-south Jefferson onto the wider and less congested east-west Maxwell. Vendors began to prosper.

In 1891, The Chicago Daily Tribune described the distinctive appearance of the Maxwell Street District: “One can walk the streets for blocks and see none but Semitic features and hear nothing but the Hebrew patois of Russian Poland [Yiddish]. In this restricted boundary, in narrow streets, ill-ventilated tenements and rickety cottages …. every Jew in this quarter who can speak a word of English is engaged in business of some sort … everyone is looking for a bargain, and everyone has something to sell … The principal streets in the quarter are lined with stores of every description …. In a room of a small cottage forty small boys all with hats on sit crowded into a space 10 x 10 feet in size, presided over by a stout middle-aged man with a long, curling, matted beard, who also retains his hat, a battered rusty derby of ancient style. All the old or middle-aged men in the quarter affect this peculiar head gear.”

An estimated 50,000 people lived in the compressed area in 1910. Three story brick tenements were built in the early 1900s, with stores on the ground floors, and storage of merchandise on floors above. Upper floors in the tenements were often converted to garment manufacturing or sweatshops. Rear structures were added to many buildings to accommodate expanding businesses.

From morning to evening shoppers filled the streets in a bazaar of store-front shops, push carts, fruits and vegetable stands, used-clothing stalls, kosher meat and poultry shops, bakeries, dry goods merchants, vendors of kitchen-wares and notions, shuls (synagogues), tailor-seamstress and shoe repair shops, pawnshops, cheders (schools), mohels (circumcisers), shadchans (marriage brokers), doctor and lawyer offices. The consumption along Halsted Street was more upscale. Literally “pullers” cajoled, shoved, and pushed bargain hunters into the department stores.

In a narrow urban space, Maxwell Street matured into a full-service economy. In dollar terms, it became the third largest grossing business district in Chicago. Enduring discrimination against their quaint appearance and alien tongue outside the West Side district, Maxwell Street area residents had no good reason to leave the ghetto and spend their money elsewhere with all their needs and desires for provisions, goods, and services immediately at hand. bjb

INTRODUCTION

PHOTO GALLERY

OUR RUSSIAN EXILES

THE RUSSIAN JEW IN CHICAGO ed. CHARLES S. BERNHEIMER (1905)

Charles S. Bernheimer was an American journalist, born in Philadelphia in 1868, educated in public schools, a Ph.D. in Education from the University of Pennsylvania in 1896. He read papers and published articles on topics of his special interest: social settlement work, activities of the immigrant Jewish population, and immigration in general.

He was Assistant Secretary of the Jewish Publication Society of America when he compiled and edited the anthology, The Russian Jew in America (1905). It centered on three independent cities: New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago.

Bernheimer intended his effort to contribute shading and hues within an historical mosaic. He worked to expand the complexities of the Jewish “character” beyond an earlier “melting pot” for Americanization and assimilation dramatized by Israel Zangwell in Children of the Ghetto (1892). Zangwell’s production had created a sensation in England and America. Among his admirers was Jane Addams.

“Russian Hebrews” was a census category. It concentrated the immigrant Jewish population in urban areas in significant numbers in the thirty years before 1905. The studies commissioned by Bernheimer for this volume diverged from presenting a single type in a single city, so commonly perceived by outsiders. Seen one Jew seen them all! The cumulative evidence in the mosaic of Bernheimer’s Chicago testified to a core of common facts without any comprehensive unity. bjb

- Philip Davis, A.B., “General Aspects of the Population: Chicago,” p. 57-60

- Minnie F. Low, “Philanthropy: Chicago,” p. 87-99

- Abraham Bisno, “Economic and Industrial Condition: Chicago,” p. 135-146

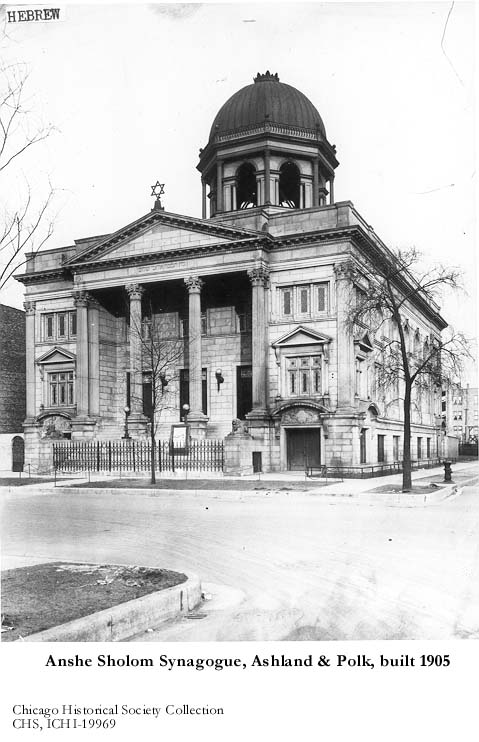

- Mrs. Benjamin Davis, “Religious Activity: Chicago,” p. 172-182

- Philip Davis, “Educational Influences: Chicago,” p. 211-219

- I.K. Friedman, “Amusements and Social Life: Chicago,” p. 249-254

- Elijah N. Zoline, “Politics: Chicago,” p. 277-79

- Kate Levy, M.D., “Health and Sanitation: Chicago,” p. 318-333

- Elijah N. Zoline, “Law and Litigation: Chicago,” p. 360-363

GROWING UP HILDA SATT: WEST-SIDE GIRL

A Jewish woman, Hilda Satt Polacheck was born in Poland circa 1885 and migrated to Chicago with her family in 1892. Her father, educated both in languages and mathematics and having learned the art of carving from his father, became a tombstone carver by trade, a skilled and well-paid occupation.

Polish, Russian, and German nationalists hated each other, but they hated the Jews living among them even more. The Polacheck family lived well in Poland when the peasants believing the Jews killed Christ were incited to the retaliation of Pogroms. Moreover, the Russian Army’s sustained efforts at impressing Jewish sons into harsh compulsory military service accelerated the exodus of the Jews to the U.S. The pervasive corruption of public officialdom in Eastern Europe provided Jewish families a way out. Bribery of officials was the currency at every level of policing and permissions.

In Warsaw in 1891 Hilda’s father heard about planning for the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893. With the worsening political, religious, and cultural environment, he made the decision to move his family to the U.S. His homemaker wife from a well-to-do family did raise objections to leaving. Nevertheless, the father secured a good position as the only tombstone carver qualified in Hebrew, Yiddish, Polish, Russian, and German inscriptions for the Chicago Jewish community. And he arrived in Chicago in time to visit the Columbian Exposition.

In Chicago, the family lived in comfort on South Halsted Street until 1894, when the father died suddenly at the age of forty-four, leaving behind an impoverished widow and five small children. With no training outside the home, and unable to speak English (which she never did learn), Dena Satt now had to support her bundle of children. As a single mother and immigrant, her options were all degrading: charity, scrubbing floors, or taking in wash. Not for her. With small kids in tow, she began laboring up and down multiple flights of tenements stairways, and over the years became a relatively successful street peddler fluent in Yiddish with a regular clientele

For twenty years Hilda’s mother made a go of supporting the family, continually moving addresses in the Maxwell Street area in response to the cost of rent and limited family resources. After twenty years, Hilda’s itinerant mother plying the streets and frequently moving addresses was a mirror image, an alter ego to Jane Addams comfortably settled inside Hull-House Settlement. They represent the gulf on Halsted Street between peoples who were in close physical proximity: so close yet so far apart culturally. Only once in twenty years did Mrs. Satt enter Hull-House and meet Miss Addams, with Hilda as translator.

Hilda was a good student at the Jewish Training School, but typically Jewish family resources were reserved for the education of male sons and brothers. At the legal age fourteen Hilda left school and as was expected of her she found work to assist in the support of the family and herself. Growing up on local streets and working at a variety of local jobs, she became embedded in the working lives of the neighborhood, vividly depicted later both in her original short stories and in pages of memoirs. Regarding her subsequent career as a social worker after her husband’s death, she numbered among the few fortunate girls to become a protégé of Jane Addams in Hull-House with the opportunity for higher education.

Hilda’s daughter, Dena Epstein, generously provided the manuscript assembled after Hilda’s death with editorial comments and family photos. bjb

Memoir by Hilda Polacheck, I Came a Stranger, ed. Dena J. Polacheck Epstein

- South Halsted Street by Hilda Polacheck

- South Halsted Street, Comment by Editor

- My Father by Hilda Polacheck

- My Father, Comment by Editor

- My Mother by Hilda Polacheck

- My First Job by Hilda Polacheck

- My First Job, Comment by Editor

- Growing Up by Hilda Polacheck

- Growing Up, Comment by Editor

- Oasis in the Desert by Hilda Polacheck

- Oasis In The Desert, Comment by Editor

- Hilda Satt, “The Old Woman and the New World” The Butterfly 3, no. 10 (October 1909): 4-5.

Hilda Polacheck, Federal Writer’s Project, Folklore Collection

- The Dybbuk of Bunker Street

- Pack on My Back

- I Sell Fish

- Dust

- Little Grandmother

- A Prince Comes to Halsted Street

PHOTO GALLERY

COMING-OF-AGE: JEWISH WORKING GIRLS ON THE WEST SIDE (1909-1913)

Jewish families in eastern Europe would send their daughters to work and with luck land husbands in America. As they matured, these girls commonly were taught skills by their mothers in sewing trades. In the U.S. they were often neither bashful nor passive about improving their lives and indeed protesting labor exploitation in the mass production threads and garment business. bjb

- The Immigrant Girl in Chicago by Elias Tobenkin (1909)

- The Jewish Immigrant Girl in Chicago by Viola Paradise (1913)

My First Eighty Years by Bernard Horwich (1939)

Bernard Horwich, a financier and philanthropist, aided many organizations whose mission was to improve Jewish lives on the West Side of Chicago. His autobiography My First Eighty Years remains a vivid account of his childhood as a Jew growing up in Russia, his education in business in East Prussia, his experiences as a Jewish immigrant to Chicago who rose to financial wealth and contributed to Jewish philanthropic organizations.

Born in 1863 in Ponieman, Suwalk, a province under the Russian Empire, Horwich’s father Yankel was a scholar who met his mother when housed by her family as a charity student. He remembered his mother as a “loving despot” who repeatedly and abusively punished her children with the confidence that God would forgive her.

As a teenager, Horwich worked in Königsberg, East Prussia. Initially a charity student, he saved up money and went into business as a grain broker. His success was short-lived. The German Government in Berlin decreed that only certified foreign businessmen were permitted to remain in the country. Foreign men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five might be permitted to remain if they became German subjects and volunteered for the Army.

Seventeen at the time, Horwich had few options but to depart for the United States. Upon advice from a relative, he traveled immediately from New York to Chicago. He was quickly disillusioned when he learned that there was a general dislike of “greenhorns” on Chicago streets. He was attacked with stones when looking for his cousin’s address on the West Side.

Moreover his cousin’s living conditions distressed him : “I finally reached my cousin’s home on Forsythe Street, and its wretched and neglected appearance almost made me sick. A Talmudic student and one of the leaders of a synagogue, Itze knew nothing about business or earning a livelihood, but spent his time in study. His wife, a very clever businesswoman, was the breadwinner. She peddled dry goods, selling on the installment plan, and was away all day. My cousin, therefore, was the housekeeper, and a poor one at that. They had a girl and two boys, and they all lived in a small flat on the third floor, consisting of three rooms, besides the kitchen.”

Horwich soon learned that even the German Jews who immigrated to the U.S. long before the Russian and Polish Jews were not welcoming to the more recent arrivals. The attitude of German Jews in the U.S. towards their Russian and Polish “poor cousins” was that of superiority and unpleasant pity. The Ashkenazi or Eastern Europeans reflected badly upon the enlightened and established assimilated Germans. The Russian Hebrews were merely tolerated by their German betters who had achieved rank, status, and success because they were Jewish

As Louis Wirth, a German Jew on Chicago’s West Side, observed, the “poor cousins” were capable of responding to their “betters” in kind. “When I first put my feet on the soil of Chicago, I was so disgusted that I wished I had stayed in Russia. I left the old country because you couldn’t be a Jew over there and still live, but I would rather be dead than be the kind of German Jew that brings the Jewish name into disgrace by being a Goy. That’s what hurts: They parade around as Jews, and down deep in their hearts they are worse than Goyim, they are meshumeds (apostates).”

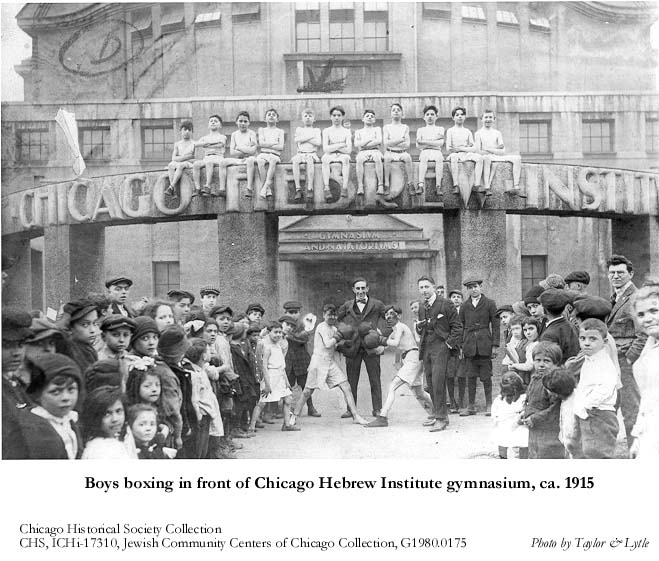

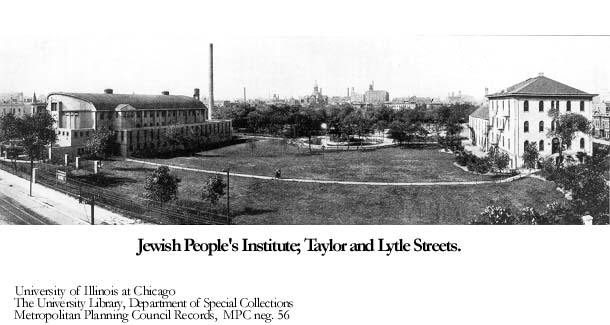

Horwich began his career in the Chicago Ghetto peddling stationary in the streets. Over time, he worked his way up to become president of two banks and a stakeholder in other enterprises. As a wealthy businessman, he founded organizations to improve the conditions of Jews on the West Side. Among them, the Hebrew Literary Society, Order of B’rith Abraham, Chicago Hebrew Institute, Chicago Zion Society, and with the help of Leon Zolotkoff, the Order Knights of Zion, in which he was the first grand-master. He financially aided war victims of Poland and Lithuania in 1919. His crowning achievement was the founding of the Federated Jewish Charities. In Chicago today, the Bernard Horwich Jewish Community Center commemorates his good name. bjb

- Chapter 1: My Boyhood in Poniemon, p. 1-45

- Chapter 2: Starting Out in the World, p. 51-104

- Chapter 3: The Land of Opportunity, p. 105-129

- Chapter 4: Early Chicago, p. 130-155

HULL-HOUSE ORAL INTERVIEW

JEWISH INSTITUTIONAL LIFE

- The Jewish Training School of Chicago by Rebecca Farr

- Philip Seman and the Chicago Hebrew Institute by Eliot Zaschin

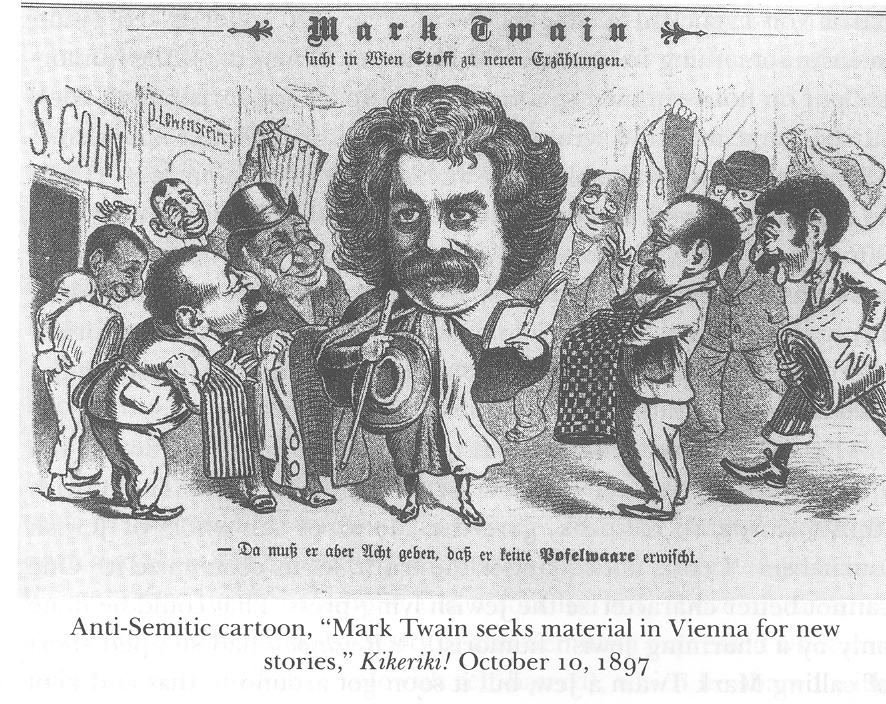

“DER JUDE MARK TWAIN”: WAS MARK TWAIN JEWISH?

Twain was a Southerner, not born to tolerance. Nevertheless, unlike his treatment of the Irish, Mexicans, and Native Americans at whom he poked fun without mercy, he joked relatively little about Jews. It pleased him when his daughter Clara married a Jewish musician. His books translated in Yiddish were popular on New York’s lower east side. When Sholem Alechem the Yiddish humorist was called the “Jewish Mark Twain,” Twain replied, “Please tell him that I’m the American Sholem Aleichem.” bjb

- “Der Jude Mark Twain”: Was Mark Twain Jewish? by Burton J. Bledstein

- Concerning the Jews by Mark Twain (1899)

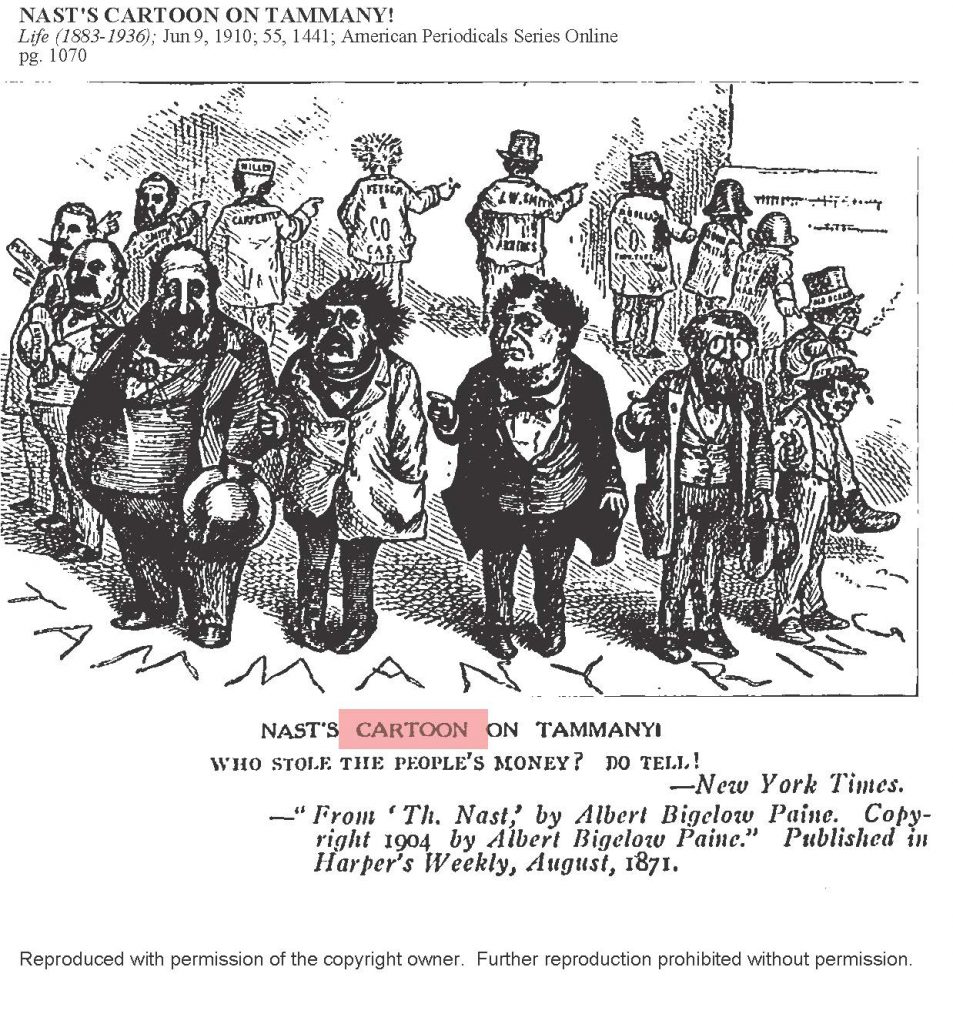

JEWS: POPULAR CARTOONS

Political comedy functions by caricature, lampoon, satire–pricking the hot air of narcissist self-exaggeration and flatulent official pronouncements from the ambiguities and complexities within a person’s experience. In U.S. magazines and newspapers in the later 19th century, editorial cartooning on politics and culture–local, national, international–became a popular comic art form.

By means of a talented caricaturist and snappy caption, the target of the cartoon received instant recognition in the eyes of a gleeful beholder. A grandiose subject of current interest was diminished to grossly earthy dimensions through laughable humiliation and perverse mockery and ridicule. Raw and unforgiving, cartooning democracy cultivated the “art of ill will.” Nothing and no person was sacred, immune from graphic scorn as a damned “fool”–a vain buffoon, maker of their own gullible foolishness.

“Stop them damned pictures” Boss Tweed of the Tammany Hall political machine is reported to have said after seeing Thomas Nast’s cartoon, “Who Stole the People’s Money.” “I don’t care so much what the papers say about me. My constituents can’t read. But damn it, they can see pictures.”

Three essential characteristics made for the successful magazine and newspaper cartoon presentation.

One, minimal reflection required. The ridiculed target was instantly recognized and the satirical message immediately understood abetted by brief captions. Well-intended do-gooders as well as stupid alien nationalities and bungling racial buffoons immediately became a threat to well-being.

Two, laughter, mirth, and humiliation, exposing the ludicrousness of vanity and self-righteous propaganda of an adversary were more effective weapons than historical physical confrontation, banishment, dungeons, even jails. Cartooning was effectively combat by different means.

Three, a direct correlation between the numerical frequency of the appearance of a cartoon subject in print media and its importance in the immediate lives of the viewing audience. Political comedy fit in the vulgar American slang genre of “bullshit”–“money talks bullshit walks”–first appearing in the later nineteenth century, and prospering since.

The large number of cartoon images of Jews in the American city, both the more prosperous Germans and poorer Russian-Hebrews, featured an accomplished skill among them for sharp, “vulgar,” and pushy practices. The names Cohen, Levy, Jacob, Israel identified by captions with a thick Yiddish dialect, were clear giveaways. Aggressive rule-breaking commerce was their vocation, and pursuit of The Almighty Dollar their passion. The modern antisemitic caricature of the Jewish plan for global domination in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1903) was present in the mock world of cartooning. Henry Ford funded a printing of a half-million copies of The Protocols distributed throughout the U.S.. bjb