CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

MAXWELL STREET POLICE

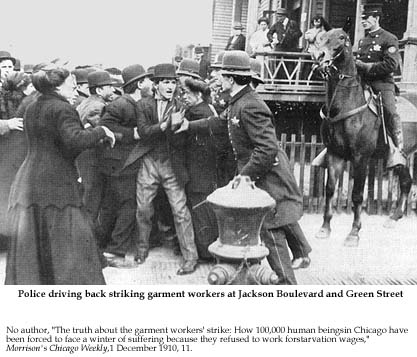

Strong disagreement and violent argument about the practices of the police in Chicago were embattled topics of controversy in the early 1900s, and they remain so today. Inside a neighborhood–“bloody Maxwell”– and bloody Chicago today, history does matter.

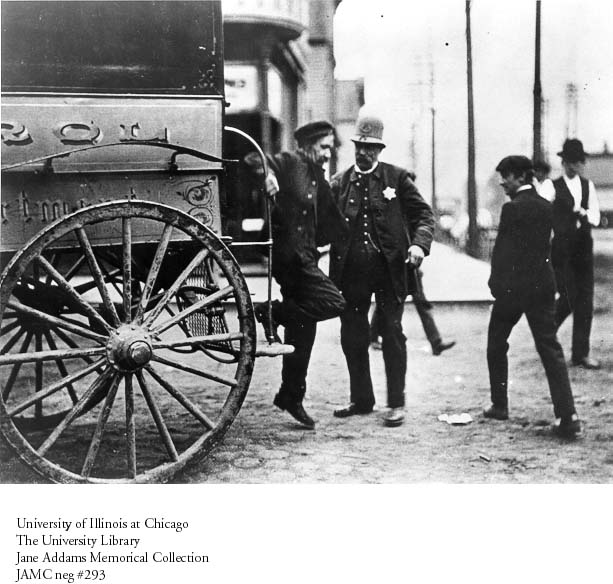

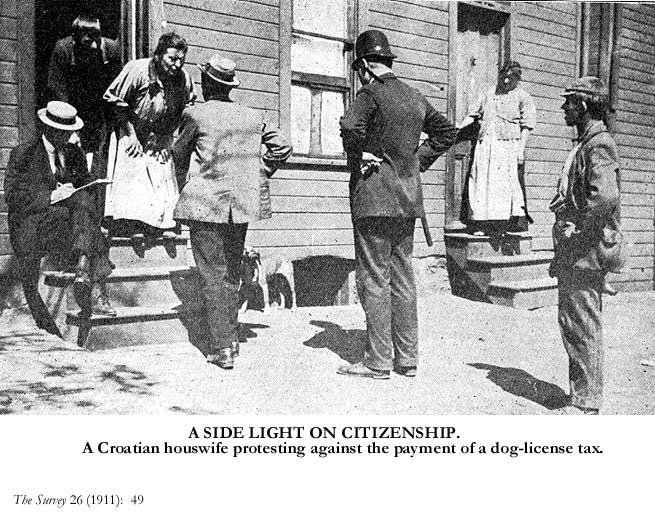

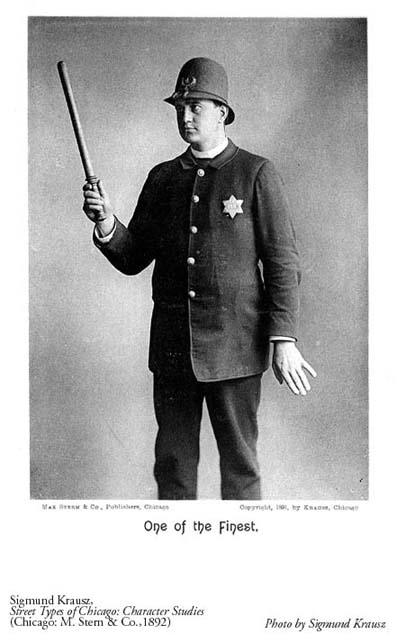

Police were a pervasive physical presence on West Side streets. In the daily lives of working people the cop on the beat had a more immediate physical presence than garbage collectors, street sweepers and other city workers. Graphically they represented the ethnic and economic politics of the the city. The reality was that the police department provided a large pool of patronage jobs accessible to politicians who benefited by the churn in spoils from owning public offices.

Small favors from street vendors, free services by food services, friendly contributions to appeals for charitable funds were among the euphemisms for “pay-offs” in the lexicon of reformers. Contributions were expected as an expression of gratitude. The police commanded allegiance in the name of public law and order–a bulwark against criminals preying on the streets and anarchists plotting revolution,.

In the West Side slum and ghetto, early arriving Western European Irish and German immigrants dominated the police force to the exclusion of later arriving Russian Jews, Italians, and Greeks. Insider ethnic allegiances within the police hardened their class biases which cast scorn on more recent and poorer immigrants. As “alien” nationalities from Southern and Eastern Europe crowded the streets with substandard housing and a lack of sanitation, the West Side neighborhood persisted in a state of perpetual agitation.

Both city courts and the public opinion of the better classes often employed loose and politically flexible definitions of criminal activity. City newspapers in the 1890s enthusiastically began reporting in prurient detail a litany of abuses, atrocities, and morbid goings-on in “Bloody Maxwell”–the “Wickedest District in the World.”

The Maxwell Street Station, the 7th District red brick and limestone fortress of a building at 943 West Maxwell (corner of Morgan and 13th St.) with three foot concrete walls at the base was designed in 1888. It was among the city’s responses to the labor riot and aggressive police actions at Haymarket in 1886. As a representative Chicago police station in the roughest of urban districts, the appearance of the physical structure received iconic status and became a monument to urban nostalgia. In 1981 the picturesque 19th-century Maxwell Street Station at 943 Maxwell Street in Chicago was chosen to be the facade in the popular TV production “Hill Street Blues” set in New York City.

Behind the picturesque facade in the early twentieth century was hard-core politics, and no small amount of abuse (not for the nostalgically inclined). Captains who ran the precincts or districts were generally independent of central authority. The justification for local control was the capacity to respond in a timely way to local interests and concerns, even when pay-offs and bribes determined which complaints received the most attention. Moreover, the ladder of the chain of command demanded military submission by subordinates to orders.

Black officers, for instance, were prohibited from arresting white citizens, and were never assigned as supervisors for white officers. Both the ethnic cultures and common practices of the Chicago police enforced de-facto segregation. The 1919 Race Riot was set in motion when a white officer patrolling the beach refused to arrest whites suspected in the fatal stoning of a black swimmer.

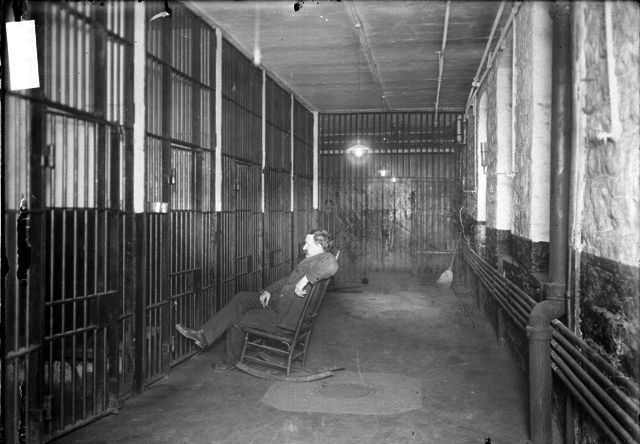

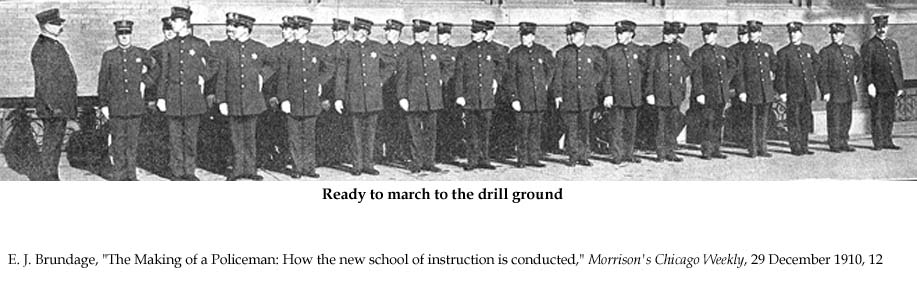

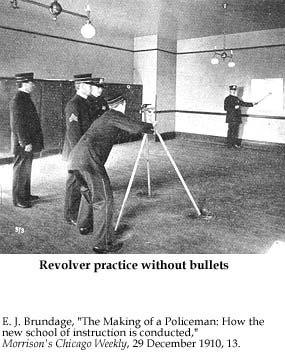

Formal requirements to join the force were few before 1895 and no formal training was required before 1910. Though the work environment was often boring–patrolling for long hours, much of it at night, and standing in reserve at the Station house for emergencies–policemen were compensated by better pay than most manual workers. Commonly they were only fired for political cause. Cops with a work culture of brawny masculinity, family fealty, and generational succession held onto their plumb jobs, and kept them within the family by passing them on to their sons.

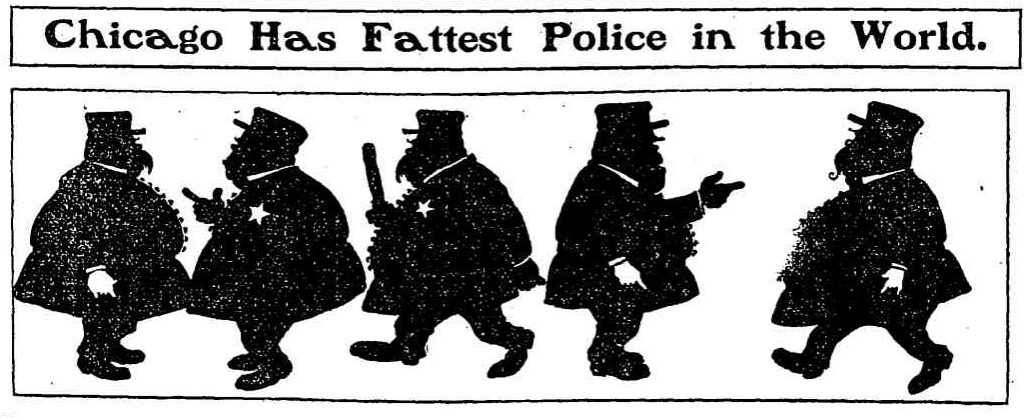

“Chicago has Fattest Police in the World”: mocking caricature in Chicago Daily Tribune (January 20, 1901). bjb

INTRODUCTION

- Perspectives on Chicago Police: West Side by Burton J. Bledstein

- History of Maxwell Street Police Station by University of Illinois Chicago Police

- Maxwell Street Police Station by Nancy Plax

PHOTO GALLERY

“BLOODY MAXWELL” (1891-1921)

- Was It Accident Or Murder? (1891)

- Chopped To Pieces, Murdered by Her Nephew (1892)

- Police Fight a Mob, Fierce Conflict with West Side Thieves (1895)

- Brains Own Sister, Uses a Bludgeon with Horrible Effect (1896)

- Footpads Murder To Rob (1900)

- Shoots Fiancee, Kills Himself (1902)

- Woman Dead, Seven Held, Brutal Beating (1902)

- Police Befriend Cocaine Dealers, Hull House Fights On (1906)

- The Wickedest District In the World (1906)

- Machinist Kills Wife With an Ax, Arrested in Barroom (1907)

- Two in Custody as Boy’s Slayers, Dismembered Remains are Identified (1908)

- 1 Dead, 5 Hurt in Vendetta, in West-Side ‘Little Italy’ (1910)

- Police Defy Mob In Arrest, Two Armed Italians Taken by ‘Crime Squad’ (1910)

- Jobless Riot and Battle Police, March on Maxwell Station After Capture of Nihilist (1914)

IN THE HARRISON STREET POLICE STATION

An unflattering picture of the cruel fate of locals on city street gushed up from a new brand of investigative journalists and reporters. Among the earliest and most widely distributed was British newspaper editor William T. Stead’s inflammatory expose, If Christ came to Chicago! A Plea for the Union of All Who Love in the Service of All Who Suffer (1894). In the lead off chapter, Stead heralded religious indignation against hapless and vulnerable victims in the Harrison Street Police Station on Chicago’s west-side.

From the pulpit, Chicago was a city of “great sin,” and Stead carefully chose the target of his campaign for his new publicist brand of reform labeled “government by journalism.” His many readers were not disappointed by his Dickens-like descriptions of the dark realities of police and political abuses. “Harrison Street Police Station is one of the nerve centers of criminal Chicago.” bjb

ACCUSATIONS OF POLICE BRUTALITY, CONFRONTATIONS: (1893-1914)

- Row In A Synagogue, Russian Jews Have a Red-Hot Battle (1893)

- Tons Stolen Junk, Police Uncover Immense Quantities of Goods (1895)

- Catch Fourteen at One Swoop, All in Rogue’s Gallery (1896)

- Thieves Active On West Side, Many Complaints of Petty Robberies (1898)

- Dying Man In A Cell, Police Mistake Illness for Drunkenness (1900)

- Raid Sidewalk Merchants, on Jefferson Street Eight Arrests of Clothing Dealers (1901)

- Says Police Robbed Him, Denies Charge, Head of Department Clears Bluecoats (1901)

- Accuse Police Of Brutality, Maxwell Street Men Ready to Tell a Few Things Also (1902)

- Girl Beaten, To Quiz Police Maxwell Street Force Will Be Investigated (1908)

- Court Calls Copper Brute, Beats Boy, ‘Disgrace to the Force’ (1909)

- Haunts of Pickpockets and Protection By Police Revealed (1914)

ALEXANDER PIPER, POLICE REFORMS (1904)

Prompted by cynicism and ongoing criticism of the Chicago police for lax standards, bad practices, failure of discipline, and unfitness for duty–among the many accusations–the “good government” City Club in Chicago engaged Captain Alexander Piper and his New York Detectives to present its membership with an external independent investigation. In dramatic fashion, Piper’s findings were summarized by leading headlines in the Chicago Daily Tribune on March 20, 1904. bjb

CHICAGO POLICE FOUND WANTING. WEIGHED BY CAPT. PIPER AND DECLARED INEFFICIENT, INSUFFICIENT UNDISCIPLINED AND UNFIT. OFFICERS AND MEN HIT

- Chicago Graft Only Sporadic, No Systematic Corruption (1904)

- New Police Stars to be Used by Chicago Department (1904)

- Chicago Police Found Wanting, Declared Inefficient, Insufficient, Undisciplined, and Unfit (1904)

- Police Reforms Will Be Thorough, Will Have Discipline (1904)

- Expose Police Pending, Vice Trust is Alleged (1906)

- Trial Only A Starter, Will Oust Corrupt Men (1906)

“PIPERIZE” A SCANDAL: CHICAGO SLANG (1905-1910)

“Piperize” was Chicago vernacular slang for informers who exposed the filth of graft and corruption within the institution, set in motion the “sweeping” out of the stable, and brought insider placeholders to a reckoning. Not a word found in the dictionary. bjb

- Club Women to Piperize (1905)

- Trial Board to Piperize (1905)

- Proof of Graft (1906)

- Yale University Shocked (1907)

- Piperize Office (1910)

- Garment Workers Piperizing (1910)

COPPERS IN CHICAGO (1894-1915)

- They Try For Stars (1894)

- Coppers Cold And Dry (1901)

- Duns For the Coppers, Aphorisms (1901)

- Policeman Aids In Blowing Safe (1902)

- New Copper Wide Awake (1906)

- Trail Board Acts Ousting Coppers (1907)

- Fat Copper Wants Pension (1909)

- Things Coppers Can’t Do, a Book Full of ‘Em (1909)

- ‘September Morn’ Copper, Back To Street Duty (1914)

- Law Is At Fault, Police Honest (1915)

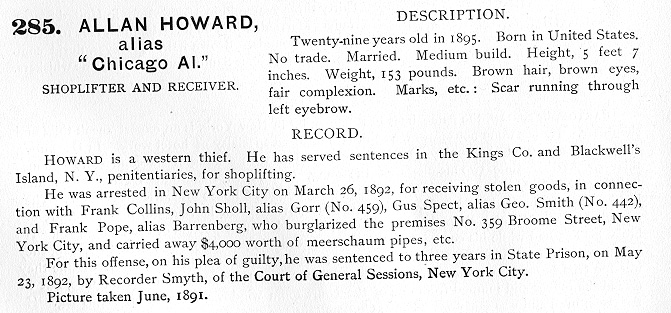

MUGS- ROGUES GALLERY

“Mug” is a slang term for face, dating from the 18th century. Faces were a way of reading “character” and the stark photographs of high-profile or known wrongdoers were intended to keep a record and alert the public to active criminals on the wanted list in a Rogues’ Gallery. Basic information can appear on a placard on the photo itself or a wrap sheet attached to the photo. (See Alan Howard alias “Chicago Al” Shoplifter and Receiver.) By the 1870s the Pinkerton National Detective Agency with an active presence in Chicago and the Midwest had the largest collection of mug shots in the nation.

By intent mug shots and rogues’ galleries had prejudicial consequences against individuals in the public domain. For example the Chicago Police photographed juvenile suspects, often picked up for minor offenses, and neither removed the photograph nor any documents casting suspicion from the archives when the youth was released as innocent. The origins of a “surveillance state” appeared with the photographic power of facial recognition in the nineteenth-century mug shot, mug books, and rogues’ galleries.

In the prominent examples from an 1870s mug-shot collection, the criminal mugs appear crazy demented (psychopaths) with insane and scary restless eyes. Avoid these low-life characters for fear of your well-being. In the 1880s a change in visual appearance occurred with the advent of professional criminals. The well-groomed every man and every woman in the mug could be your friendly next door neighbor, a ministering “rabbi,” or an innocent-looking bystander next to you on the platform station. A hard-to-detect criminal threat now lurked in the crowded city in most familiar public and private places. Who really is your neighbor in fact? Who would have guessed what fraudulent schemes of larceny and theft lurk in the hearts of men? bjb

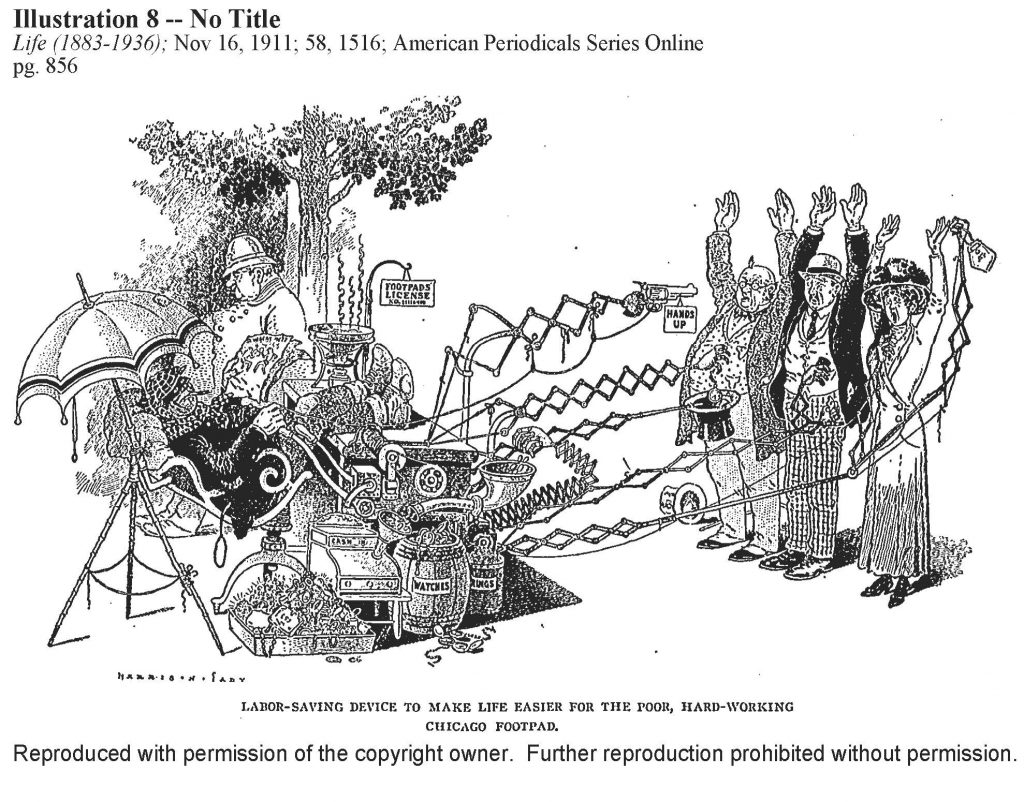

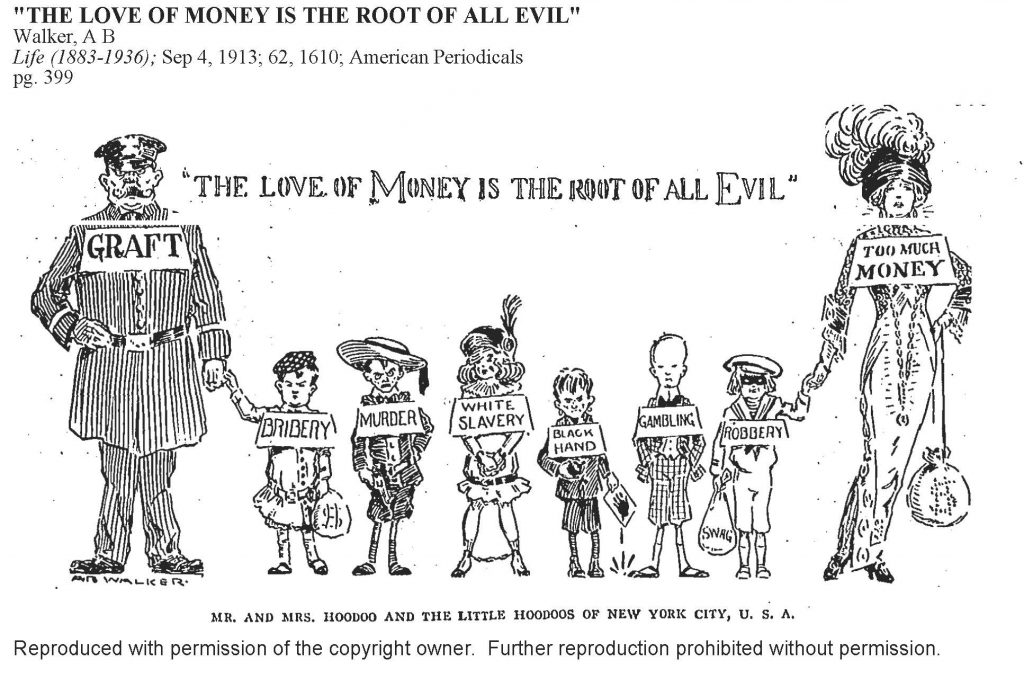

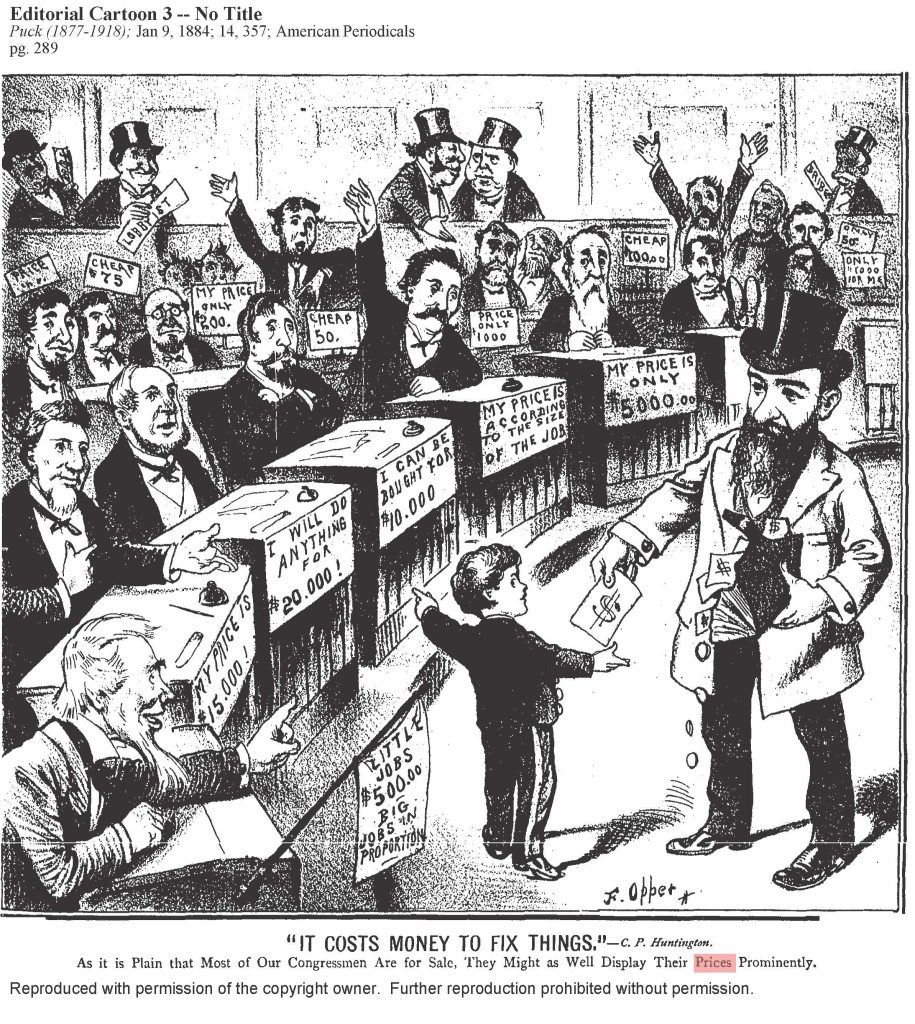

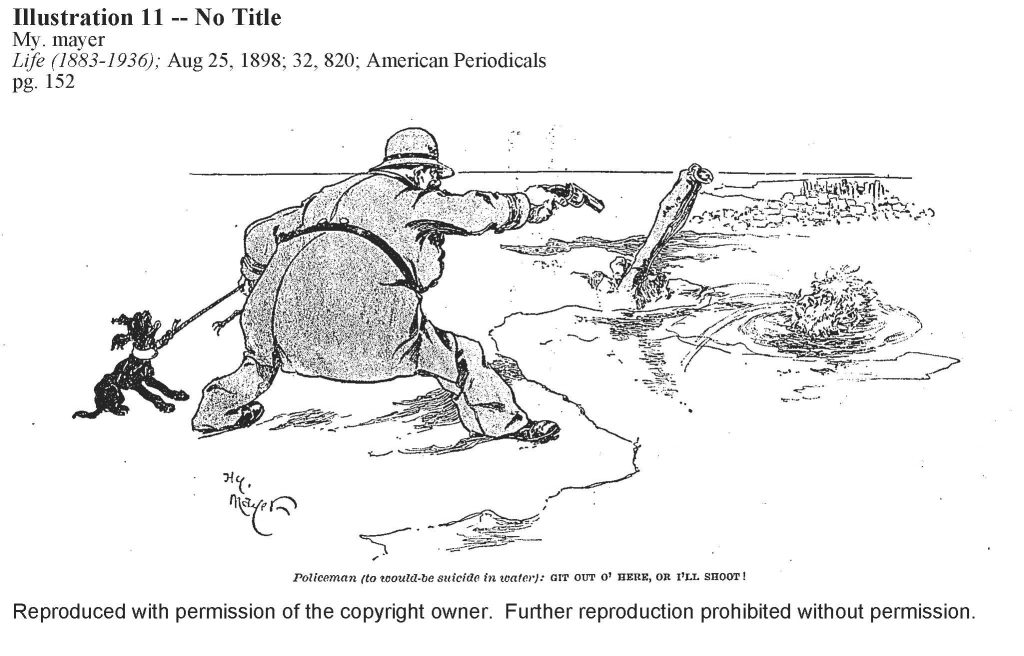

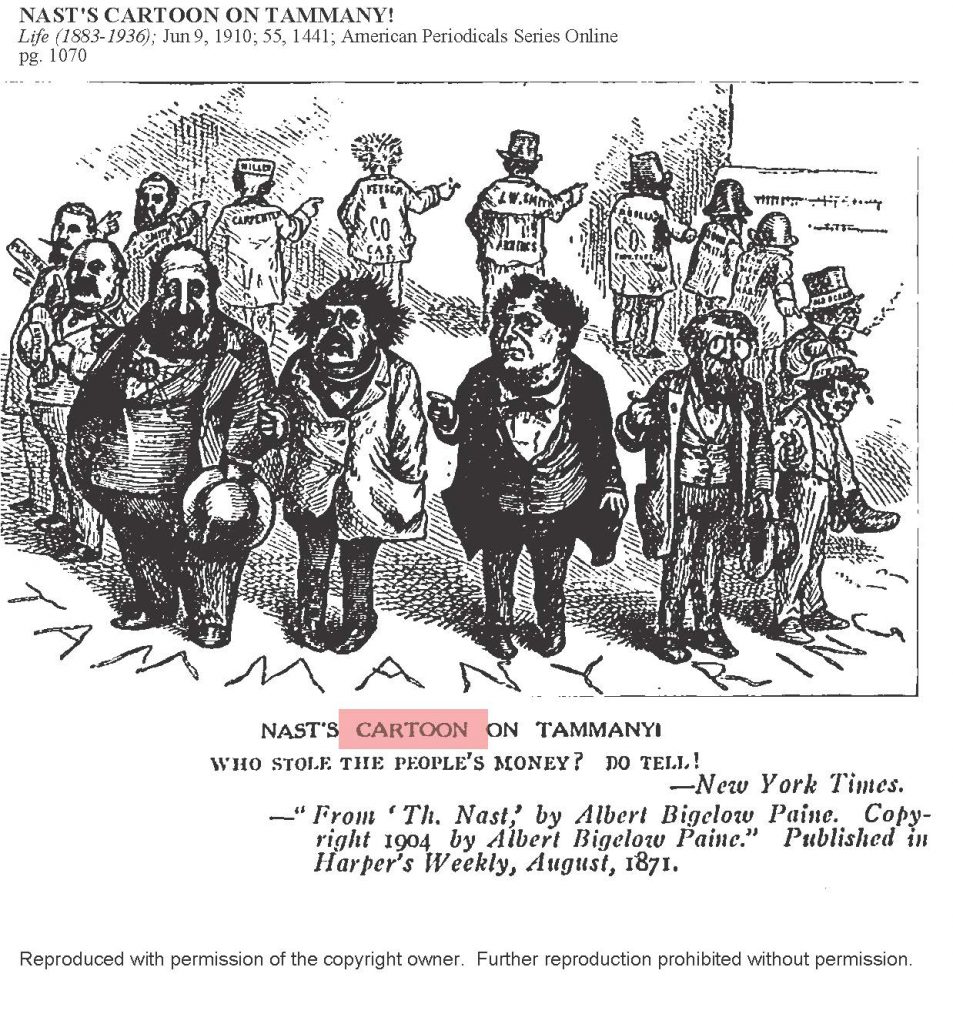

COPPER AND POLICEMAN: POPULAR CARTOONS

Political comedy functions by caricature, lampoon, satire–pricking the hot air of narcissist self-exaggeration and flatulent official pronouncements from the ambiguities and complexities within a person’s experience. In U.S. magazines and newspapers in the later 19th century, editorial cartooning on politics and culture–local, national, international–became a popular comic art form.

By means of a talented caricaturist and snappy caption, the target of the cartoon received instant recognition in the eyes of a gleeful beholder. A grandiose subject of current interest was diminished to grossly earthy dimensions through laughable humiliation and perverse mockery and ridicule. Raw and unforgiving, cartooning democracy cultivated the “art of ill will.” Nothing and no person was sacred, immune from graphic scorn as a damned “fool”–a vain buffoon, maker of their own gullible foolishness.

“Stop them damned pictures” Boss Tweed of the Tammany Hall political machine is reported to have said after seeing Thomas Nast’s cartoon, “Who Stole the People’s Money.” “I don’t care so much what the papers say about me. My constituents can’t read. But damn it, they can see pictures.”

Three essential characteristics made for the successful magazine and newspaper cartoon presentation.

One, minimal reflection required. The ridiculed target was instantly recognized and the satirical message immediately understood abetted by brief captions. Well-intended do-gooders as well as stupid alien nationalities and bungling racial buffoons immediately became a threat to well-being.

Two, laughter, mirth, and humiliation, exposing the ludicrousness of vanity and self-righteous propaganda of an adversary were more effective weapons than historical physical confrontation, banishment, dungeons, even jails. Cartooning was effectively combat by different means.

Three, a direct correlation between the numerical frequency of the appearance of a cartoon subject in print media and its importance in the immediate lives of the viewing audience. Political comedy fit in the vulgar American slang genre of “bullshit”–“money talks bullshit walks”–first appearing in the later nineteenth century, and prospering since.

The proliferation of cartoons appearing with “coppers” and policemen on the beat speaks to their active engagement in the daily lives of city people. Political comedy functions by pricking the smelly air of official flatulence from the ambiguities and complexities of local experience. Laugh and smirk and be historically informed.

The “coppers” job was open-ended unlike most working class jobs in the city. Policemen responded at once to a range of real human needs as well as the political necessities of questionable business interests especially protecting liquor or clamping down on labor actions. Ethnic resentments festered, and the perspective of comedy and mockery was a form of truth-telling more effective and satisfying than irreversible physical confrontation.

Police work was liminal, an ambiguous activity, as caricatured in cartoons Irish brawn or brains; the lawman played for a sucker by a mock victim or outwitting the clever con; the persistent challenges presented by ever present street-wise kids; the greenhorn cop in a rough neighborhood at risk for doing something stupid. bjb

- Another Brazen Highway Robbery (1882)

- He Had Read Of Mason Craze (1882)

- New Policeman On The Beat (1883)

- Amateur Photography (1884)

- Steady Watch (1884)

- Amplified Ads (1886)

- No Nurse-Girl Should Be Without One (1886)

- Baffled Policeman (1887)

- Evading The Law (1887)

- Young Malefactor (1887)

- A Harbinger Of Spring (1888)

- Republican Party-Protection (1888)

- Wicked Tramp-Watchful Captain (1888)

- Cassidy’s Mistake (1888)

- He Could Afford To Wait (1889)

- Killin’ A Policeman (1889)

- Move On Now (1889)

- That All-Absorbing Thought (1889)

- A Likely Story (1890)

- A Lost Sensation (1890)

- Not To Be Caught In That Way (1890)

- Want To Cross Little Girl (1890)

- A Conscientious Copper (1891)

- The Weaker Vessel (1891)

- Green On The Force (1892)

- Private Service (1892)

- Bad Outlook For Him (1893)

- Suburban Policeman (1893)

- Prepared For An Emergency (1894)

- Recant Lamentable Occurrence (1894)

- The Policeman In The Picture (1895)

- Don’t Scorch Now Mama (1897)

- Get Out Or I’ll Shoot (1898)

- A Diverted Pursuit (1899)

- Financial Note (1899)

- A Kneaded Retreat (1900)

- An Escape (1900)

- Show Me Your Permit (1901)

- The Better Part (1901)

- Money Talks (1902)

- What’s The Charge Against The Prisoner (1903)

- A Corner In Copper (1906)

- Copper Unsteady (1909)

- Suffragette (1910)

- Resistin’ An Officer (1911)

- Sir I’ll Call A Policeman (1911)

- Traffic Policeman At Home (1911)

- Thankful ain’t A Copper (1914)