CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

LOUIS WIRTH SOCIOLOGIST (1928)

Louis Wirth was born in Gemunden on the Maine, Germany, son of a relatively prosperous cattle-merchant and small-scale farmer, one of only twenty Jewish families in a village of nine hundred persons. Until age fourteen, Louis went to local schools operated by Protestant Evangelicals. He received extracurricular lessons in the basement of the synagogue from the local Rabbi and an itinerant Hebrew teacher. Very few youths from Gemunden matriculated to the academic level of a Gymnasium. In the meantime Louis’s three uncles had migrated to America. In 1911 one proposed bringing Louis with him to Omaha NE to attend public high school and receive a liberal education unavailable in the provincial ethnocentric Rhineland village.

Upon graduation from high school, Louis rejected the career in retail business planned for him by his family. In 1914, he entered the freshman class at the University of Chicago. In 1919 he graduated and began a career in social work as director of the division for delinquent boys for the Jewish Charities of Chicago. He married a non-Jew, the first in his family.

By means of his wife’s salary as a social worker, he returned to graduate school in Sociology at the University of Chicago in 1922. In 1924 he submitted a M.A.Thesis, “Cultural Conflicts in the Immigrant Family.” And in 1925 he completed a Ph.D. dissertation, “The Ghetto: A Study in Isolation.” In 1928 with no significant revisions beyond dropping the subtitle, he published the dissertation manuscript with the University of Chicago Press.

Generally speaking, Wirth was open-minded and pragmatic, skeptical at being harnessed to any particular theology, ideology, or dogmatism. His primary interest as a sociologist with a social work background centered on the novelty of human beings in historical, cultural, generational, and emotional transitions.

After New York and Warsaw, Jews in Chicago were the third largest concentration in the world with a difference, “a more diversified set of characteristics in its various parts than either of the other two.” In Chicago, Jews displayed more independent creative life and fewer persistent theological and intellectual othodoxies than in New York’s older and much larger ghetto .

In the new academic discipline of urban sociology, Chicago’s “ghetto” located at the intersection of Halsted and Maxwell in the slum of an industrial city was not usefully studied as a mirror-image of New York City’s Lower East Side. The latter was in many ways an old-world village “shtetl” dominated politically by centuries-old animosities between majority nationalities and defensive minorities.

The West Side of Chicago was “the most varied assortment of people to be found in any similar area of the world.” It presented a real-life laboratory containing adversarial immigrant and race colonies, None held a majority or remained in the same place more than one generation or so before moving to second and third settlement residential areas in the city and suburbs.

Wirth was attentive to social processes of assimilation, adaptation, and inclusion. He observed for example that in a little more than one generation on Chicago’s West Side,“the Poles and the Jews,” sworn and hateful enemies in their native land, continue “to detest each other thoroughly” but they now “trade with each other very successfully.”

Antisemitism persisted as a menacing presence and barbaric reality in the Polish homelands. In the U.S. and Chicago, Wirth emphasized successful institutional activities like the Anti-Defamation League and organized responses to Henry Ford and the modern Ku Klux Klan to contain periodic outbursts of hate.

The invasion of the West-Side ghetto by the Negro, segregated racially by the white landlords in greater Chicago, became “of more than passing interest.” Jews, Wirth observed, settled in the area “precisely for the same reason” as the Negro, and presented no “appreciable resistance” to their presence. Contrary to more antagonistic ethnic nationalities in the area, “Jewish immigrants in the ghetto have not as yet discovered the colored line.”

Why not? In an economic environment where one price did not fit all, seller and buyer successfully exchanged goods and services with an urban solvent that knew only one color. “The Negroes pay good rent and spend their money readily.” In the context of sharp cultural differences, U.S. coin was a common denominator. Coin from Anglo hands had no more value than from Irish, Italian, or Greek hands. Good business was good relationships. Wirth overstated his positive case on race congeniality, nevertheless his observation drew on useful perspectives on commercial prosperity and the role played in ghetto markets by suborned Negro labor.

Albeit a small world with a depth of emotion, Wirth’s Ghetto in Chicago was an historically dynamic institution with irreversible changes occurring over time and place in the lives of successive generations of families and individuals. The publication formalized a concept of a local place including the economy, religion, cultural mores, politics, and generational adaptations and assimilation. All these themes continue to be borrowed, explored, adapted, and re-interpreted by urban, ethnic, and minority historians and sociologists to this day. bjb

The Ghetto by Louis Wirth (1928)

- Foreword by Robert E. Park

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: The Origin of The Ghetto: Seeking New Homes

- Chapter 3: The Ghetto Becomes an Institution: The Compulsory Ghetto

- Chapter 4: Frankfort a Typical Ghetto: Historical Aspects

- Chapter 5: The Jewish Type: The Jews as a Race

- Chapter 6: The Jewish Mind: Mentality and the Division of Labor

- Chapter 7: The Ghetto in Dissolution: Social Movements

- Chapter 8: Jews in America First Settlers: The Sephardim

- Chapter 9: Origins of the Jewish Community in Chicago: The Pioneers

- Chapter 10: The Jewish Community and the Ghetto: The Growth of the Community

- Chapter 11: The Chicago Ghetto: The Near West Side

- Chapter 12: The Vanishing Ghetto: The Flight From The Ghetto

- Chapter 13: The Return to The Ghetto: Conflict and Self-Consciousness

- Chapter 14: The Sociological Significance of the Ghetto: Non-Jewish Ghettos

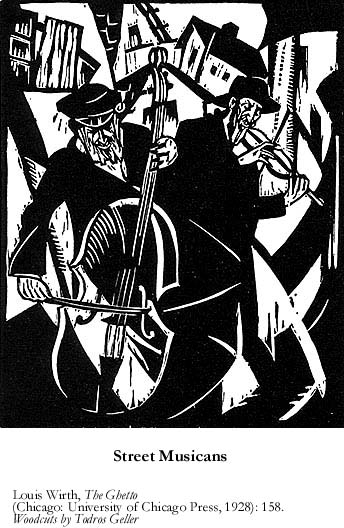

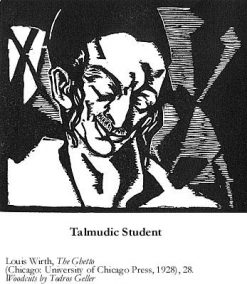

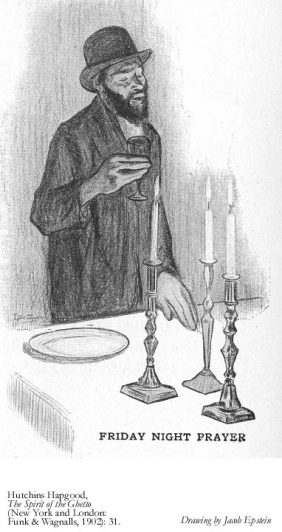

THE GHETTO, WOODCUTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS: GALLERY

The quaint and picturesque woodcut illustrations in Wirth’s text convey the old-world sectarian and provincial spirit of orthodox types in the village Stetl of mythic memory. Wirth neither acknowledged the woodcuts nor the name of the artist in his introductory credits. Almost certainly, Wirth’s mentor and the Anglo editor at the press made the decision to upgrade the publishing values of the book with artistic images separating chapters. The quaint and picturesque woodcuts resembled Joseph Epstein’s celebrated illustrations of old-world character types which adorned Hutchins Hapgood, The Spirit of the Ghetto: Studies of the Jewish Quarter of New York (1902)

A selection of contemporary photographs by the editor would have been a more suitable representation of Wirth’s text and historical discussion of the evolution of the modern urban “ghetto,” a port in the industrial city for recent arrivals to neighborhoods on the margin. bjb