CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

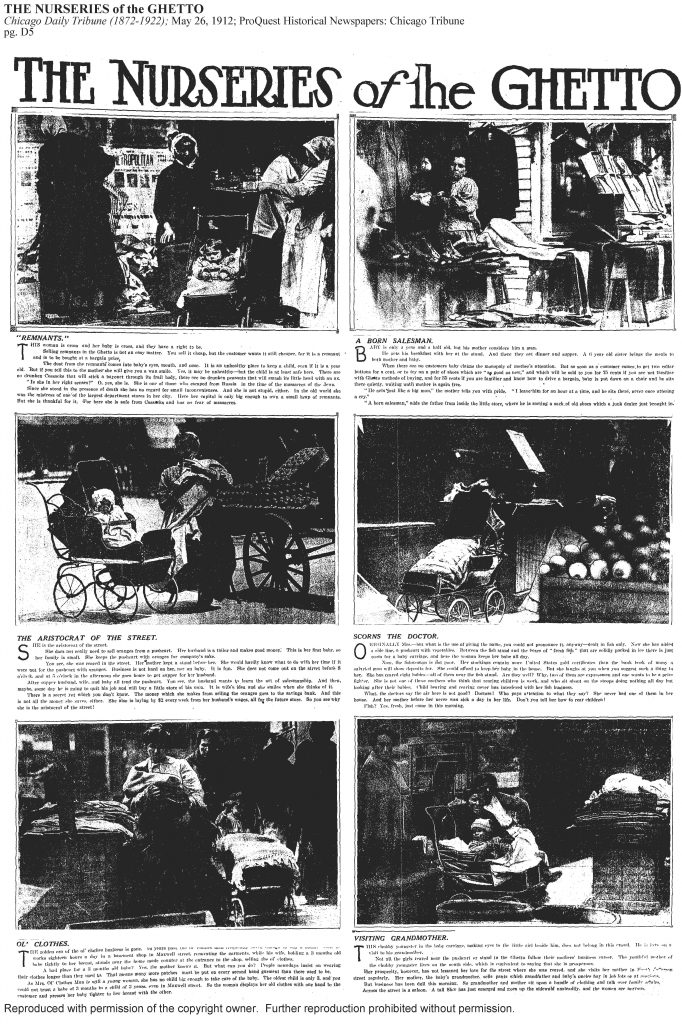

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

ELIAS TOBENKIN

Elias Tobenkin (1882-1963) was born in Belorussia, a landlocked country in Eastern Europe bordered by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Anti-semitism was prevalent in the region and the Tobenkin family immigrated to the U.S. around 1896. It settled in Madison WI.

Though the family had very limited resources Elias received a high school education in Madison. Children of the poor usually left school at age of 14 for full-time work. After high school, Tobenkin matriculated and supported his way through college at the University of Wisconsin (1902-1905). A leader in higher education in the period with the “Wisconsin Idea” promoting progressive ideas in public higher education, the University including in its orbit of studies adult education programs and university extensions. Tobenkin graduated with a B.A. in German. In 1906 a scholarship permitted him to earn an M.A. in German literature and philosophy at the University.

With the onset of the financial panic and recession in years after 1906, jobs were hard to find. Especially was this the case for Jews widely unwelcome in the Nordic settled Wisconsin hinterland. Tobenkin however was well-equipped with language skills, cultural knowledge of immigrant groups to the U.S., and a respected education.

He began his career in journalism as a reporter on the “Labor Run” at the Milwaukee Free Press. In 1907, as a freelancer having completed some reporting on working-class Chicago for the Chicago Daily Tribune, he accepted a position with the Sunday edition of the paper. His move to Chicago followed a dispute with the Free Press over his conditions of employment. Roaming west-side streets and beyond, Tobenkin penned more than one hundred substantive feature articles for the Daily Tribune between 1907 and 1913.

These were peak years for non-English speaking immigration to the Chicago region. The West Side was portal to the world as diverse ethnic and racial groups settled, moved around, and struggled to make a life and get ahead. Eighteen nationalities resided and forty languages were spoken in the vicinity. Dense with store-front shops, saloons, small factories, places of amusement, religious establishments, and tenements, everyone toiled below and above ground to get a toehold in the business friendly environment.

Not a replica of an Eastern European “shtetl” familiar in New York’s Lower East Side, Chicago’s midwestern urban “ghetto” in Tobenkin’s street reporting was an intense district of inner city business and labor activities. With an unprecedented intimacy for a reporter, he narrated multiple life-stories of personal failure and success, marital desertion, parental conflicts, generational encounters, ethnic and race friction–a “rich thicket of reality” in its human context. His beat was primarily focused on cultural persuasions at street level and not politics flowing down hill from the corridors of city hall.

Victorian publicists universally characterized urban “slums”–-the “other” half–as impoverished and diseased. Dead-beats slinked around dark back alleys, crowds swarmed in garbage-strewn passageways, criminals loitered and parasitic vice inhabited mean streets.

By way of contrast, Tobenkin graphically presented the West-Side “ghetto” not as the “black-hole” of an urban “slum”–a persuasion perpetuated in Chicago by middle-class reformers, Christian missionaries, do-good child-savers, and editors at big-city daily newspapers. Secured from the streets inside a comfortable and well-ordered cloister, the Hull-House women, for instance, never received mention over the years in Tobenkin’s prolific feature articles.

A uniquely qualified immigrant found himself positioned at the right time and in the right place to present the shifting human fortunes and unintended consequences of personal histories in a diverse and active place. Better known for his later fiction, Tobenkin left an archive of fresh and poignant primary sources of West Side life. Today it remains relatively unknown and ripe for study. bjb

CHICAGO DAILY TRIBUNE (1907-1913)

The Financial Panic of 1906 made for “hard times” in Chicago’s immigrant neighborhoods. Bank lending stopped, financial notes could not be repaid, depreciation in the value of indebted assets went “under water” (in today’s parlance). Most dramatically a lack of ready cash in the system made it difficult for multi-generational families pooling earnings and living under one roof to address their needs and “get ahead.”

“Economy becomes an art.” By any and all means at hand, vulnerable folks worked to sustain themselves in a business cycle of high unemployment. In 1907 Tobenkin began observing and detailing the diversity of schemes by which local families precariously held their economic lives together. “Hard times” made for a hard life in the overpowering present, living in the gloom of cellars, forcing children to work in home sweatshops, scavenging for pieces of coal fallen on the streets, shopping “cheaply” for food, living on ten cents a day even starving to save money, arranging a marriage with its cost-saving advantages.

Talking to people on the streets and recording their oral histories, an embedded Tobenkin gained access to human perspectives on local circumstances beyond the reach of outside observers such as sight-seeing tourists, white Anglo editors, and middle-class residents sheltered from the street cloistered within their domestic parlors. In a revealing omission, for instance, Jane Addams in her progressive reform tract Twenty Years at Hull-House (1910) neglected to acknowledge the neighborhood effects of the financial panic after 1906 on residents in the Hull-House area. Lewis Hine’s photographs commissioned by the American Magazine for Jane Addams’s Autobiography told a different story.

As Tobenkin reported, Chicago was the best labor market in the nation, and people adapted, especially local immigrant women, single and married. They were in no position to be timid or overly scrupulous about the well being of their family. bjb

- Women Of Toil Own Industries

- Starve To Save More Money, Live on 10c a Day During First Year in Chicago

- Small Tailor Bound to Fail, Big Stores Get the Trade

- Slaves of Chicago’s Europe Leave as Christmas Nears

- Skimpy Shopping in Ghetto, Bread by the Half Loaf

- Polish Magicians Get Rich; Working Girls Easy Victims

- Peddling Rugs For a Degree, Ambition In The Ghetto

- Old Folks Fail In Business, Modern Rivalry Too Keen

- Odd Trades In The Ghetto, Women Who Mend Old Bags

- Odd Trades In Ghetto, Men Who Peddle Brooms

- No Women Harness Workers, Trade is Slowly Dying Out

- Land Of Liberty A Mockery, Ghetto Curse On Columbus

- Killed and Wounded in Battles of Peace

- In the Glow of Infernal Fires, Men Work and Face Death

- Immigrant Children Slaves to Family

- Hundreds Starve In Chicago, Cases Hidden from Charity

- Hated Boss Rules Foreigner, Immigrant Tries to Flee

- A Grudge Against Thanksgiving

- Cupid Guides Ghetto Nurses, Ambition to Marry

- Four Distinct New Year Days, How Aliens Will Celebrate

- Deserted Wives In Ghetto, Find Work in Junk Shops

- Coal Pickers Fight Winter, Poverty Forces Coal Hunt

- Christmas Sad For Hundreds, Immigrant’s Prospect is Dull

- Chill Winds Bring Suffering, Shiver From Lack of Coal

- Child Slaves of Chicago, Forced to Work in Home Sweatshops

- Cellar Dwellers in Chicago, Families That Live In Gloom

- Bake Shops Go to The Wall, Bread Factories Get The Trade

- See Working Girls, Mothers, Women

1908

By 1908 the consequences on the ground of the financial recession began to ease. Money lenders and banks chased the debt business again, chances improved for the unskilled looking for jobs, street vendors and small shops continued to struggle and with the support of family labor made a go of it.

From Tobenkin’s perspective, a money-centered urban economy in the neighborhoods outside the downtown Loop was a double edged blade. On the one side, choices and careers became available for some folk. Chicago was a “land of no vacations” where it was “easy to make money” by accumulating not big bucks but a cent at a time. Chances of success, albeit precarious, could pay off. “The world is full of chances; men with eyes see them.” On the other side, despite what newspaper readers preferred to identify as the moral failure of character in poor immigrants–suffering, disease, abuse, and exploitation were never in short supply in the system itself according to Tobenkin. Drink was a result not a cause of breakdown. “What to do with human discards sad problem of the city,” he commented.

The devil was in the thicket of detail layered in each Tobenkin article. In the world of experience, no two lives or cases were quite comparable. The reporter was digging in the proverbial neighborhood weeds to document personal accounts. The process made for a rich array of variables set in a vivid verbal montage. Tobenkin’s litany of observations was lengthy.

At times Tobenkin sounded like an advice columnist responding to frequently asked questions, not unlike the popular Bintel Brief, Yiddish letters and replies published in the Jew Daily Forward in the early twentieth century. When should mothers go to work, was it bad for their children of school age? Did popular penny soda fountains and ice-cream vendors where children of the ghetto refreshed themselves act like an opiate for the evils of the slum? Why the “moving fever” in Chicago where every day of the year was “moving day”? Immigrant girls were refusing to enter domestic service, and said “no” to housekeeping positions–even as the servant problem for the middling classes worsened. Were demanding and haughty white Anglo mistresses at fault?

Tobenkin addressed many questions bewildering readers about what appeared to be contradictions in the behaviors inside “alien” colonies. Why was education a “dead asset” to a bill clerk who lost a job? Why were learned medical doctors, aristocrats in Europe, now digging ditches in Chicago? How did merchants who had no brick and mortar stores do a large and profitable retail business? Why were hundreds of Chicago’s poor richer in material assets than many of Chicago’s rich?

Tobenkin’s overview was generational. The children he observed–the core of immigrant neighborhoods—had minds of their own not predictably restrained by the wishes of traditional paternalistic families. Bilingual children comfortable on the streets were a moving force on the West Side–an “old age pension” for their poor parents. As reported the girls saw “no dignity” in the housework of their mothers. Better paying factory work with unsupervised personal time and personal dress and boarding at two dollars a week with friends better suited their new-found urban lifestyles. Moreover, those who did train to be domestics were reported to leave the job after learning, and organized strikes for better wages and benefits.

Nor were the boys in Tobenkin’s feature articles predominantly slouchers and loafers, petty thieves, and delinquents usually in trouble–the perspective from Chicago’s West-Side Juvenile Criminal Court. Ghetto boys with a “business knack” knew best the meaning of “hustle,” an asset in Tobenkin’s approved behaviors. Girls who took up the burden of their families were “the wonders of the slums.” bjb

- World Full Chances, Men With Eyes See Them

- Why Immigrant Girls Refuse To Become Domestics

- Where There Is No Room For Boys & Girls, Landlord Wants Strict Promises

- What The Picture Told

- What Race Makes Best Hobo? Good Tramp Never Works

- What To Do With Human Discards Sad Problem of the City

- Walking Banks In Chicago, Stocking is a Safety Vault

- Vacation In Street Car is Luxury of Ghetto

- Unhealthy Filth of Slums, Children Die Without Soap

- Training Girls To Be Domestics, When They Learn They Strike

- Tired Man Wants to Quarrel, Finds Fault With His Wife

- Three Months In Search of a Job, Despairing Boy Couldn’t Go Home Without It

- Think Doctor Should Be An Aristocrat, Link Medicine With Aristocracy

- Solution of Servant Problem, Does It Lie With The Mistress?

- Should Mother Go To Work When Family Purse is Low?

- Possible To Beat The Osler Theory and Start Life Anew

- Poor of Ghetto Welcome Winter Because of Chance For a Better Job

- At The Penny Soda Fountain Where the Poor Children of the Ghetto Refresh Themselves

- Patient Heroism of the Ghetto Children Lifts Many Families from the Depths of the Slums

- Office Boy a Lesson for “Bench Army… Office Boy Real “Boss”

- Merchants Have No Stores, Do Large Retail Business, Requires No Money in Advance

- Men Starve in South Chicago, Sleep in Barns and Sheds, Cannot Pay Room Rent

- How’d You Like to Live In a Land of No Vacations?

- Little Women, Wonders Of The Slums, Take Up Life’s Burdens Early, Health and Mentality Ruined

- Learned Doctors Dig Ditches, Sad Side of Immigrant Life

- Learn Housework, “No!” Say Girls, Girls Shun All Housework

- Immigrant Missed During the Hard Times, Miss News From Old Homes

- Immigrant Girl Likes America Because of Chance To Rise

- Hundreds Chicago Poor Richer Than Many of Chicago’s ‘Rich,’ Fortunes Tellers the Richest Poor, Easy to Make Money in Chicago, Takes in a Cent at a Time

- How Immigrants Are Looted When They Should Be Helped, Newcomers are Neglected

- Tiding Over Hard Times, How The Unemployed Seek Food, Throngs Looking for Work

- Ghetto Lad Star Salesman, Born with Business Knack…Great Ability to Hustle

- Ghetto Banks By the Score Lend Cash to the Needy…Women Keep Up Cash Supply

- Factory Gate is a Marketplace Where Foreigner Buys Supplies…”Cheapness” Secret of Business

- Every Day in the Year is Moving Day With an Army of Chicagoans…Explains Moving Fever

- How European Chicago Amuses Itself On South Halsted

- Education A Dead Asset, Loses Job of Bill Clerk

- College Dignity Detriment, Try to be Your Own Boss

- City of Promise For The Unskilled Worker, Season Lasts Seven Months

- Cigarette Makers Lose Health, Business Pays Slim Profits, Small Makers Lose Trade

- Children of Poor Old Age Pensions of their Parents, No Shirking of Duties

- Business Success Of Alien, Immigrant Walks Hard Road, Speaks from own Experience

- Boy Graduates of Ghetto Schools Are Heroes…Boundless Ambition of the Ghetto

- Board At Two Dollars a Week, Immigrant Girls First Home, How Diet Aids Beauty

- Alley, Playground of Slums, Crime and Disease Result, Plan How to Steal

- “Ifs” of City Underworld, Future Holds Small Hope, Drink Not Cause But Result

1909

In 1909, with the brunt of the financial panic easing, the dynamics of the commercial money economy returned to more familiar patterns. Central to Tobenkin’s attention was the dynamics of relationships: worker choices and their discontents with bosses, jobs and wages; strained conjugal ties with desertion by husbands and fathers and the difficult prospects for family life; estranged siblings with individual fates cast by parental preferences; the postponed gratification of continuing in school and the chance penalty of no benefit to income in the long run; the entanglements of installment plans and expanding consumer debt keeping money, goods, and assets flowing in a marketplace.

In Tobenkin’s snapshot view, the texture of Chicago’s neighborhood capitalism was tangibly visible. Locality fixed the relative value of the dollar. A shopper received more worth for the money in ghetto bargain centers than elsewhere in the city. Clothing sold by jobbing vendors on Halsted and Maxwell Streets pulled in the patrons.

Earnings in the small-purchases money economy flowed in scales of pennies and dollars not large bills. Few if any qualifications were called upon to enter this market, either for seller or buyer. Immigrants built business success on the hard road of perseverance. Becoming one’s own boss–working for oneself–was thought to be the best outcome. (The jocular complaint on the street became “why work ten hours for someone else when you can work sixteen hours for yourself!”)

Marriage brokers did a good trade in the ghetto, a universe where marriage could be a business contract. Families received benefits from selling and buying sons and daughters, an age old tradition. The consequences, nevertheless, were detrimental to enduring relationships. In significant numbers, husbands deserted married women saddled with a brood of children.

Tobenkin observed that rather than wallow in shame and parental reproach, many of these women began taking active control of their lives, setting up conditions of ownership where they could permanently earn their own bread, and taking realistic measures to “woo” back their lapsed spouses. They also directed their daughters towards independence in better paid factory work and self-reliant living arrangements. In select cases the daughters turned to labor organizing and unionization including advocacy for populist planks such as the ten hour day for women workers.

In Tobenkin’s big picture of immigrant lifestyles, there were no tell-tale signs too trivial to ignore. In Chicago capitalism, the parts of the individual stories were greater than the sum. Aging workers applied dyes on graying hair to conceal from bosses a devastating sign believed to point to diminishing productivity. While reformers complained that thousands with failing health worked and lived in Chicago’s “sunless” basements, business was very good. In the face of the White Anglo “perfection salad” movement for healthy food and diet, Slavs preferred to eat cake and drink, Italians suckled their new-born infants on salami, kids on the streets devoured Chicago hot dogs and ice cream–all with no discernible negative consequences.

With Chicago a “polyglot city” and a “haven for educated aliens,” the variations among nationalities in the work force, especially on the West Side, were many. Necessity plus temperament, according to Tobenkin, usually dictated an immigrant’s preferred type of work. Bohemian girls were more versatile; Norwegians more plodding and made better sailors. The tragedy of undiscovered talent was suspected among office scrub women who worked at night. The “hard lot” of children below the age of 15 forced to work harder in “child labor” later crippled them as “old young men.” bjb

- Work In Restaurants Preferred, Situation Result of Choice

- Welcome by Medicine Men, Slav Finds Two Adherents

- Tramp Family Charity Workers’ Newest Problem

- Tragedy Of Office Scrubwomen, Work at Night to Keep Up Homes: Tragedy, Pathos, and Romance

- Trades Close Doors To Boys, Apprentices Limited in Number

- How Thousands Buy Clothes on Installment Plan, West Side Gives Largest Quota

- Ten Hour Work Day For Women, How It’s Viewed From All Sides

- Success Based on Struggles, Immigrant Has Hard Road…Lowly Start Beat Training

- Slums Deserted For Suburbs, Italians Become “Town Farmers”

- Slav’s Odd System of Economy, Drink More Important Than Food

- Saloon Has Strong Rival, Picture Show the Magnet

- Residents of Sunless Chicago, Thousands Work in Basements

- “Red Card” Terror To Poor, Quarantine Adds to Misery, Prison Life Would be Better

- Pool Rooms Never Patronless, Habitues From “Leisure” Classes, Fine Place “to Kill Time”

- Chicago the Polyglot City, Haven for Educated Aliens, Foreign Colonies the Explanation

- Oldest Daughter Now in Revolt, Factory the Stepping Stone, Mother Does the Extra Work

- Odd Trades of Immigrants, Earnings Come in Pennies

- Locality Fixes Dollar’s Value, Buys More In the Ghetto

- Life Hard to Start Anew, Idleness Saps the Character

- Late Starters in Game of Life, Delay adds Zest to their Work, Late Starter Modern Product

- Keep Your Children In School, Teachers Sound Timely Warning

- Immigrants and their Work, Necessity Dictates Choice

- “Homeless” Father’s Home, Chicago the Great Shelter

- ‘Sweet Sixteen’s’ Hope, Greatest Aid to Matrimony

- Hard Lot of Old Young Men, One Result of Child Labor…Two-thirds at Work at 15

- Gray Hair Terror to Worker, Dye Hides Time’s Ravages, Gray Hair Often Tragedy

- Graveyard of Shattered Hoped, Room in Rear of Tough Saloon, Former Ambition Soon Lost

- Ghetto the Bargain Center, Real Needs not Considered, Patience Pays Him Well

- Free Information Concerning Adopted Country the Greatest Need of Newly Arrived Immigrant

- Earning Way Through School, Strong Ones Overcome Obstacles

- Doctor Matrimonial Prize, Heads List of ‘Shatchen’…Honored in Ghetto Ambition of Many Parents

- How the Deserted Wives of the Ghetto Try to Woo Back Their Husbands…Numbers in Thousands

- Burn in Winter, Freeze in July on the Hottest and Coldest Jobs…When the Accidents Come

- Brothers Estranged When Fate Frowns at One and Smiles on Other

- Bread Earning Wives on Increase, Husbands Find Joy in Idleness…Novelty Soon Wears Off

- Being Own Boss Big Difference…When You Work For Yourself…Hours Many, But Not Long

- Baby Carriages Need of Slums, Demand Far Exceeds the Supply…Treasured Possession

- Average Wage of Immigrant Greek Real Money Maker…”Piece Work” Usual System

- When Aged Farmers Move To City Lives are Full of Discontent…Younger Son Also Dissatisfied

- “Cake” Slavs’ Staple Diet, Italians Prefer Vegetables…Price Regulates the Use

1910-1912

Between 1910 and 1913 Tobenkin intermittently published feature articles in the Chicago Daily Tribune. They continue to display the feel and credibility of an informed participant-observer and commentator on the contemporary scene. bjb

- Why Edwards Quit His Job, Tired of Praise from Foreman

- Thousand of Chicago Men and Women Dress On an Allowance of $5 Yearly

- Stay West, Young Man, Rather Than Seek Fortune in New York

- “Standing Still” Brings Failure at 70, Webster Learns Big Lessons Too Late

- This Clerks 49 Years at the Ledger Answer Query, “Shall I Be A Clerk?”

- Second Hand Food Supplies Sold in Foreign Districts of City

- Searching the Nation For a Job, How Modern Industry Hits Worker

- Progress Wrecks Business of Small Harnessmaker

- Profitable Jobs For ‘Home Paper’ Readers

- Number of Baby Cabs Show Popularity of Actor in Ghetto

- Is Chicago Really Fair To Strangers? This Job Hunter Says He Can’t Get a Hearing

- How To Pick Place For Store

- How a Persevering Immigrant Became Boss of 2,400 Men in 15 Years’ Time

- How a Jobless Man Made Big Fortune Selling Jack Knives

- Chicago New Crop of Young Workers, Public School Graduates Face Life

- Chicago Inhospitable To Poor Visitors?

- Tragedy of Paint and Powder, Bane of the Women Worker

- Undesirable Aliens Sent Home, Chicago Center of Deportation

1913

- Slavs Crowd Jew From Old Ghetto, Health Menaced by Insanitary Conditions They Themselves Make

- Shift of Ghetto Adds Fire Danger to the Southwest, New District, About Twelfth and Kezie, Badly Built, Main Object to Sell

- Loop a Mixing Bowl for 647,000 Workers of All Nations and Stations

- “Jews and Modern Capitalism”

- Cheap Markets Need of Ghetto, Residents Who Sought More Healthy Homes Face Rising Cost of Living