CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

CHILD LABOR, CHILD BONDAGE: WHY CHILDREN WORK?

Greater than other grievances within industrial capitalism, the protest against child labor energized reformers across the spectrum of movements. Saving innocent children from exploitation of their labor (and their absentee immigrant mothers working outside the home) touched an emotional hot-button in middle-class reformers committed to the domesticity of the family home, the stay-at-home nurturing “mom.” As early as the 1840s, “mom and apple pie” invoked typically wholesome American values with universal appeal, “home sweet home.”

Surrendering to impulses for momentary excitement and thrills, delinquent and truant children escaped the schooling an educated class regarded as necessary for citizenship and productive lives. The nation must protect “its most precious asset,” wrote Florence Kelley, “the young children who will be the nation when we of the present generation are gone.” Restraining the evils of child labor, and the business interests profiting from it, reached large audiences with a broad humanitarian appeal.

By way of contrast, the earlier reform movements focused on improving the material environment–housing reform, street sanitation, occupational disease. They relied for evidence largely upon scientific “expertise” and professional studies. Evidence pointing to long-term damage to the child’s capacity for growth and maturity was more difficult to explain, especially to many recent immigrants who responded that the hard work and obedience to family and bosses good enough for their kids was good for everyone. Reformers often appeared as privileged elite white folk with protected childhoods and family supported high school and college educations now meddling in the very different lives of inner city immigrant residents.

Indeed, child labor was an age-old phenomenon. What then was the fuss about? Working or laboring children on subsistence farms in local agriculture had been the historical norm for centuries. In early modern cultures the child, “a small adult,” had the demographic probability of not surviving to adulthood. The reasoning was that procreating adults, not children, in groups under population duress could always produce additional expendable children replenishing the family and the labor force.

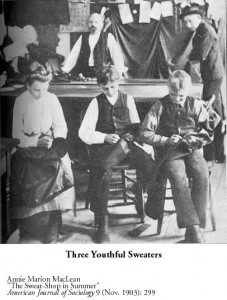

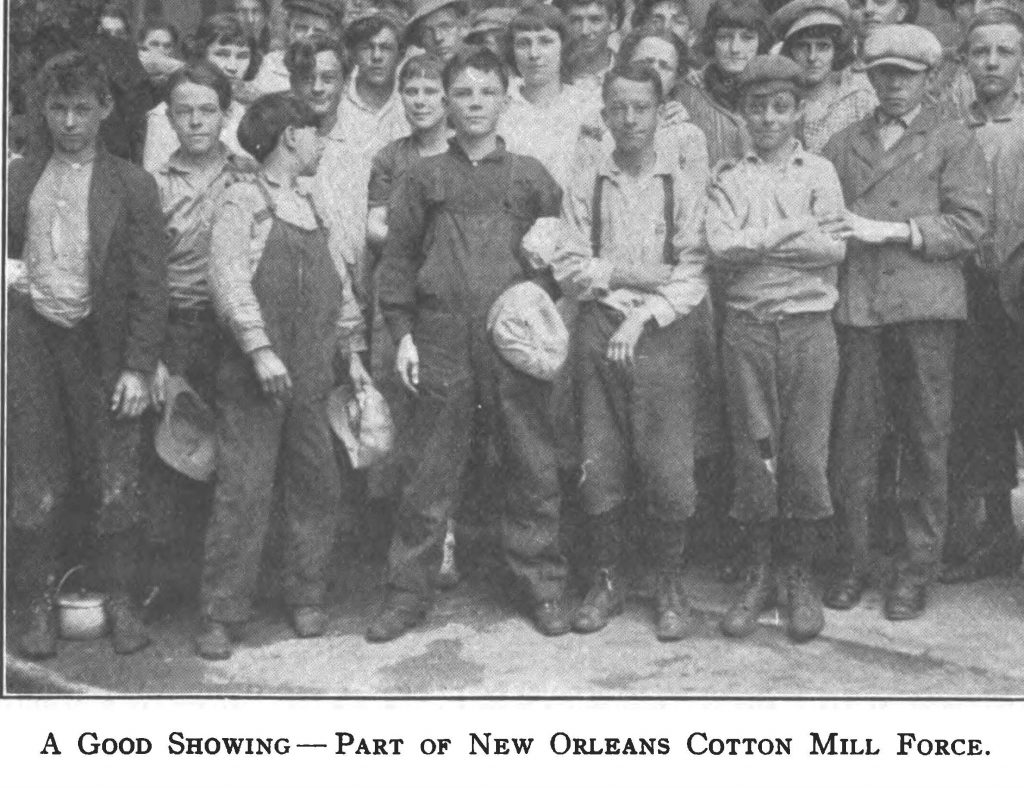

What changed was that industrial cities in 19th century Britain now brought graphic literary attention to the bleak plight of impoverished laboring children from the lower ranks and classes. Millions of poor children (with parents often in debtor’s prison) below the age of sixteen worked excessive hours for meager piece wages under dangerous insanitary conditions for punitive bosses in mines and manufacturing, in home sweating production, as domestic servants and apprentices, in street trades and sex trades. In the industrial employer’s bottom line, expendable child labor was cheaper than longer-term investment in labor-saving machinery and occupational-safety equipment.

In 1900, according to U.S. census numbers, 22% of the white male workforce fell into the 10-15 years range, and 46.4% of the non-white male workforce. Corresponding, 10.2% of the white female workforce fell in the 10-15 years range, and 30.1% of the nonwhite female workforce. Up to two million white children were at risk of exploitation, from the perspective of the child labor reformers. Non-white children received little if any notice. bjb

INTRODUCTION

- Labor’s Role In Abolition Child Labor by Erin Connolly

- National Child Labor Committee and Lewis Hine by Summit Patel

- The Rhetoric Of Child Labor by Joshua Mullen

PHOTO GALLERY

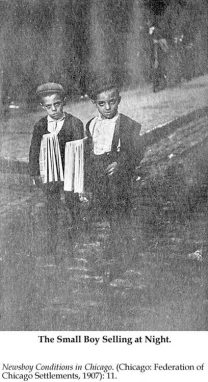

CHILD LABOR ON CITY STREETS by EDWARD CLOPPER (1912)

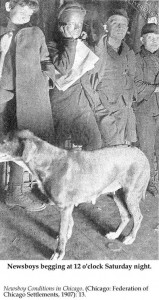

Edward N. Clopper, Ph.D., was Secretary for the Mississippi Valley National Child Labor Committee. He published extensively on child labor practices both in mills and agriculture in the rural South and on city streets in the industrializing North. He concluded that street trades–newsboy, bootblack, peddler– were a neglected form of child labor that would have been banished long ago if the practice was not so familiar a presence in everyday lives. Unregulated “child labor in our city streets”–work that could be done by adults even crippled ones with disabilities–“is productive of nothing but harmful results.” Clopper’s graphically described urchins shivering on street corners. As a professional reformer, the limits of his vision were evident. In a zero-sum game he privileged children by penalizing cripples. bjb

- Bootblacks-Peddlers-Market Children

- Effects Street Work On Children

- Messengers-Errand-Delivery Children

- Newspaper Sellers

- Street Work-Delinquency

CHILD BONDAGE, THE PADRONE EVIL IN CHICAGO (1897-1907)

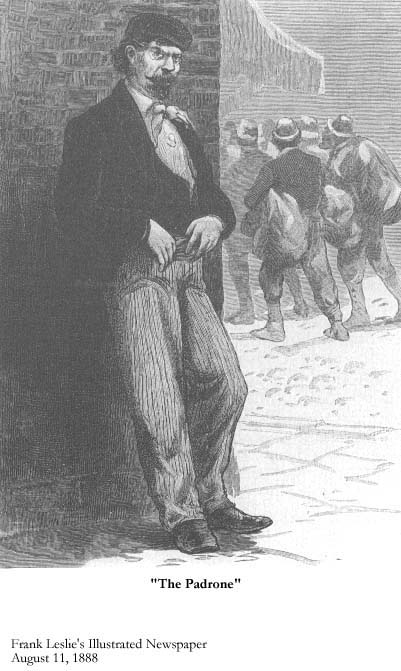

The Padrone, an Italian word for boss or manager, was a patriarchal figure in a system of temporary contract labor.

A middleman the Padrone was a labor broker matching unskilled mostly urban immigrants with temporary jobs in areas of a labor shortage, picking field crops, manual labor in mining and construction, digging canals. The clientele included women and young children, primarily Italians and Greeks, .

Ideally the Padrone served in two roles. As a facilitator assisting uninformed immigrants ignorant of the capital-intensive American labor system. And as a benefactor and counselor to his dependent patrons, providing a range of services including the costs of transportation and lodging, sending money home, writing letters, and producing documents.

More realistically, the Padrone exploited and enslaved his mature but especially his young wards, charging excessive fees for his services, and requiring submissive obedience. The record was mixed but it trended to abuse. bjb

- Padrone Evil as it Exists in the Italian Colony of Chicago (1897)

- Padrone Evil is Great (1897)

- Children Bought and Sold in Italy and Greece (1904)

- Farming Out Greek Boys in Chicago (1907)

CHILD LABOR in SWEATSHOPS (1892-1909)

- Woodworkers Protest Against Child Labor (1892)

- Marked Increase of Sweatshops in Chicago (1896)

- Child Labor In Chicago (1901)

- Police Help the Clerks; Advise Person to Avoid the ‘Unfair’ Merchants (1902)

- Strengthen Child Labor Bill (1903)

- Will Inspect Sweat Shops (1903)

- Factories In The Homes, Law Evaded by Hundreds of Parents (1904)

- Warring On Child Labor, Inspector go to Ghetto ‘Workshops’ (1904)

- ‘Forelady’ Tells of Child Slaves, Driven till Ready to Drop, Paid a Pittance (1906)

- Child Slaves Of Chicago, Forced to Work in Home Sweatshops (1907)

- Hard Lot Of Old Young Men, One Result of Child Labor (1909)

WHY CHILDREN WORK, THE CHILDREN’S ANSWER (1903-1913)

- The Sweat-Shop In Summer by Annie Marion MacLean (1903)

- A Prayer For Children Who Work by Walter Rauschenbusch (1909)

- Why Children Work, The Children’s Answer by Helen M. Todd (1913)

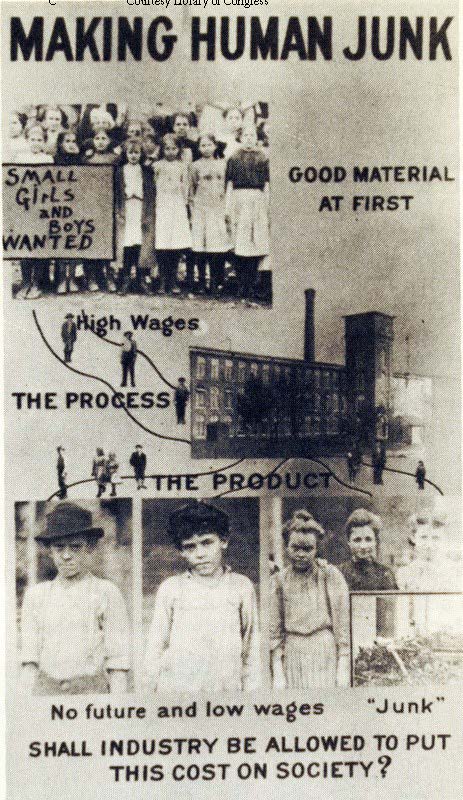

POSTERS, MAKING HUMAN JUNK: NATIONAL CHILD LABOR COMMITTEE

The National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) formed in 1904. By 1907 the organization had attracted national support with a Board of Directors including prominent progressive reformers such as Jane Addams and Florence Kelley who had been exposing pernicious child labor practices since the turn of the century.

Strenuous resistance to child labor prohibitions came alike from working-class families and low-wage employers. In the push-back, the question asked was beyond factories and sweatshops were all work places covered by the child labor legislation? Street trades and domestic help in family settings were not.

Discouraging doubts concerning the would-be beneficiaries of legislation stoked public opinion. Did children prefer mandatory schooling that seemed to have no relevance for their present or future lives whwen they could be putting money in their own and the family pocket?

Were schools commonly underfunded by tax revenues prepared to absorb hundreds of thousands of new unprepared students, often foreigners, who required remedial education? Were middle-class families with their own financial burdens prepared to pay for it? Were local police authorities prepared to enforce the law against working children of neighbors, friends, and even their own children?

The main venue of the reformers was conferences, papers, and publicity exhibiting posters like “making human junk.” Speaking to the like-minded, the effect of the movement in northern but in particular southern states was minimal, especially in mill-town regions. In response, the NCLC proposed in 1912 to create a federal children’s bureau, The United States Children’s Bureau in the Department of Labor and Commerce. The NCLC and the federal agency worked both at the federal and state level to sponsor child labor reforms for the next thirty years. bjb

- A Child’s Creed

- A National Menace

- Accidents

- Child Labor Today

- Every Child Should Work

- Everybody Pays-Few Profits

- Homework Destroys Family Life

- Making Human Junk

- Normal Men & Women

- Products We Ignore-Young Workers

“PHOTOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION” BY LEWIS HINE: NATIONAL CHILD LABOR COMMITTEE

Following his time at the University of Chicago, Lewis Hine became a teacher at the Ethical Culture School in New York City. Continuing to depend on his salary from teaching, in 1906 he picked up part-time work traveling as a free-lance photographer for the National Child Labor Committee. It commissioned pictures primarily to ornament lengthy written reports and proceedings and and to mount exhibits. Publicity from photographs and visual presentations was intended to generate a higher profile for the social work organization, an objective which proved difficult to attain.

The inner circle of the NCLC leadership was indifferent when not hostile to photographs as sensationalism, rejecting them as a cognitive visual investigation of child labor. Hine was treated, in his own words, “as sort of a handyman for social welfare conventions and the like that wanted some bare walls filled up.” A hired hand at NCLC, he often did not receive credit for his prolific work visualizing actual children at laboring tasks on city streets, in work places, and southern mills.

In 1909 the social work journal, Charities and The Commons, soon to be renamed The Survey, published Hine’s first extended photo-story “Child Labor in the Carolinas” “Some Human Documents.” The lead byline went to A.J. McKelway of the NCLC inner circle with diminutive recognition of the staff photographer. Florence Kelley, a known critic of the use of photos as sensationalist distractions from the weight of statistical and expert knowledge, agreed to pen the introduction.

Kelley’s response was startling. In the “ingenuity of a young photographer,” she stated, the “camera carried conviction” serving to mobilize public opinion where the presentation of the text, numbers, and pages of data did not. The irony was not lost on Hine, who later commented, “by the impetuous and imperious Florence who until I brought in that load of bacon, had ‘no use whatever for photographs in social work.’”

In his subsequent work as a full-time professional photographer, Hine established the use of photographs not as a genre of aesthetic art but a fresh use of documentary visual evidence in an investigative record. Photographing laboring children Hine knew what he was up against in his battle of wits against the industrial capitalist “guardians” of “special privilege.” His portable camera, hidden beneath his coat in the mills, was a stealth technology bringing to light hitherto dark and private spaces contradicting the glossy presentations of advertised corporate images of industrious and happy workers.

Moral scruples came to the fore, and Hine fended off accusations of being a “sneak” and practicing “deception” as a low-life voyeur. Employers were not about to allow cameras they did not consent to inside work places, especially where they were profiting greatly by cheap child labor. Respectable public citizens were very nervous accusing Hine of violating privacy and the proprietary rights of newspaper publishers even mill-owners.

Sensitive to the criticism and his own reputation for veracity and honesty as a photographer, Hine noted in response: “One thing made me extra careful about getting data 100% pure when possible. Because the proponents of the use of children for work sought to discredit the data, and especially the photographer, we used,–was compelled to use the utmost care in making them fire-proof. One argument they did use, ‘Hine used deception to get his child-labor photos, naturally he would not be relied to tell the truth about what he found.’”

In Hine’s seminal 1909 essay, “Social Photography: How the Camera May Help in the Social Uplift,” he hammered home his point: “The Photograph has an added realism of its own. It has an inherent attraction not found in other forms of illustration …. while photographs may not lie, liars may photograph …. see to it that the camera we depend upon contracts no bad habits.” bjb

REFORMERS ON CHILD LABOR LEGISLATION (1902-1914)

Florence Kelley, Edith Abbott, Sophonisba P. Breckinridge, Jane Addams, among others, reform women with considerable experience on Chicago’s West Side were invested in presenting the arguments and working for legislation restricting if not abolishing child labor in Illinois and every state in the U.S. bjb

- Child Labor Legislation by Florence Kelley (1902)

- Child Labor Legislation and Methods of Enforcement in Northern Central States by Harford Erickson (1905)

- Test Of Effective Child Labor Legislation by Owen R. Lovejoy (1905)

- Enforcement Child Labor Legislation in Illinois by Edgar T, Davies (1907)

- Obstacles to Enforcement of Child Labor Legislation by Florence Kelley (1907)

- Study of the Early History Child Labor In America by Edith Abbott (1908)

- Child Labor Legislation by Sophonisba P. Breckinridge (1909)

- Child Labor a Menace to Civilization by Felix Adler (1911)

- Child Labor And Delinquency by Fred S. Hall (1914)

JANE ADDAMS ON CHILD LABOR: MOTHER BELONGS AT HOME (1896-1907)

- A Belated Industry by Jane Addams (1896)

- Trade Unions And Public Duty by Jane Addams (1899)

- Danger In Child Labor by Jane Addams (1902)

- Child Labor and Pauperism by Jane Addams (1903)

- Mother Belongs at Home by Jane Addams (1904)

- Child Labor Legislation, a Requisite for Industrial Efficiency by Jane Addams (1905)

- The Operation of the Illinois Child Labor Law by Jane Addams (1906)

- National Protection For Children by Jane Addams (1907)

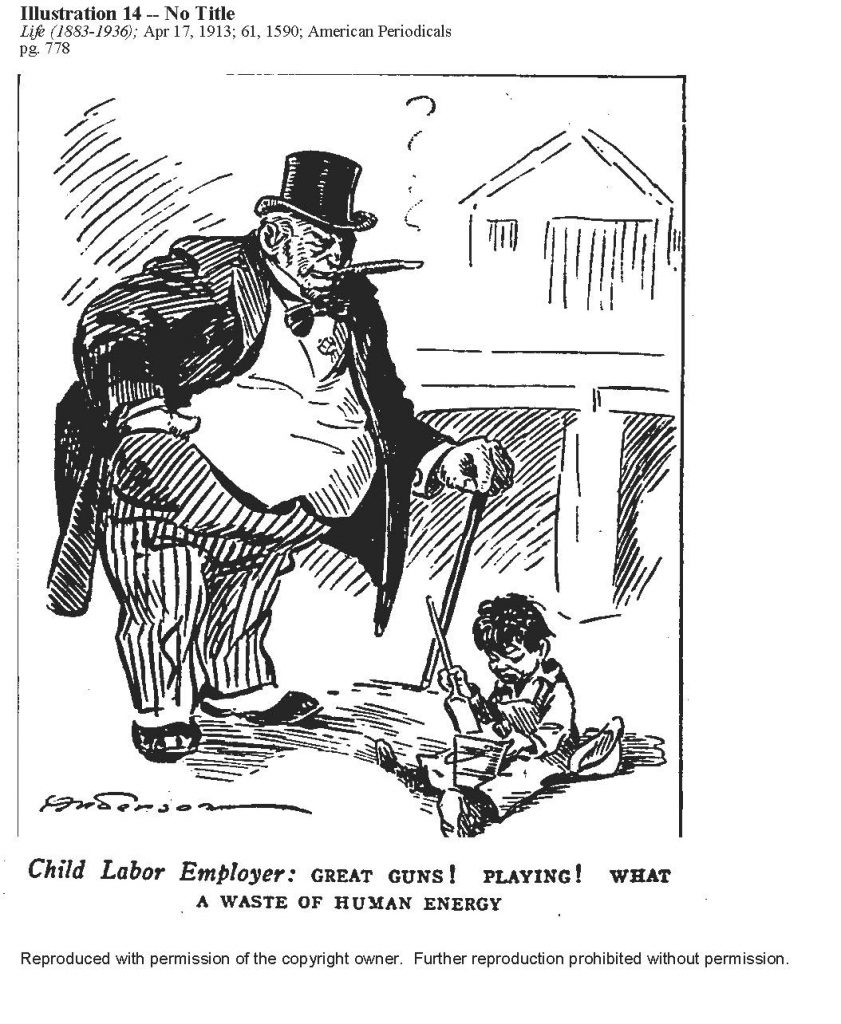

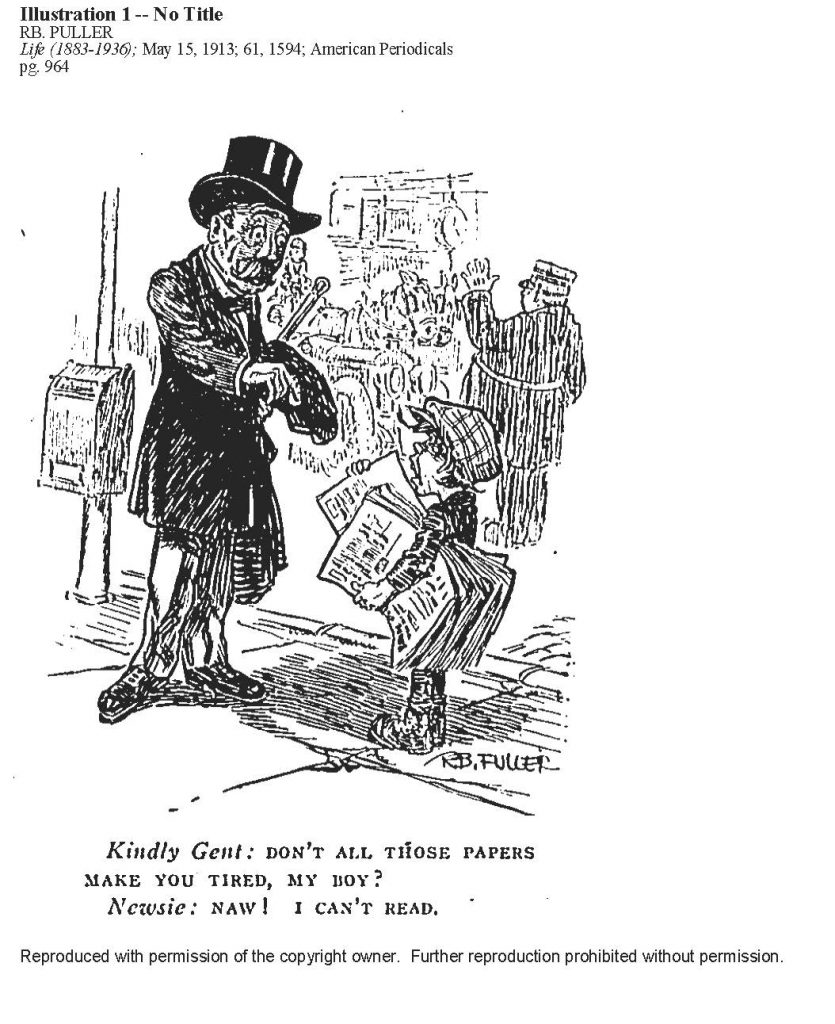

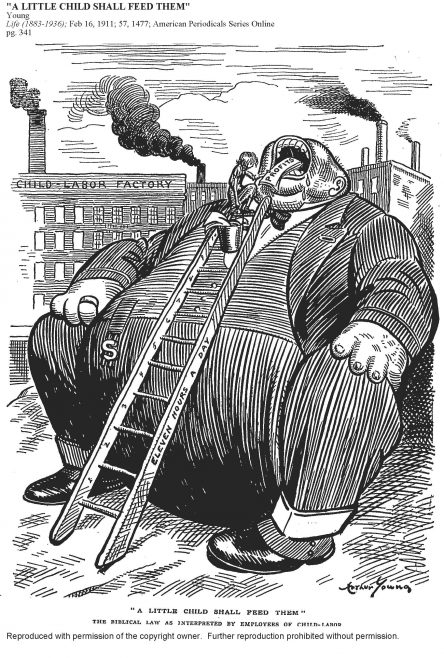

CHILD LABOR (1911-1913): POPULAR CARTOONS

Cartooning child labor slavery, and caricaturing the plutocratic greedy exploiters lent itself to satirical derision and mockery. “Great guns, playing, what a waste of human energy,” the bloated capitalist money-bags inveighed against the street urchin. Working cheaply for me allows for more muscular exercise than mere play, and instills a work ethic in the character of hapless youth upon whom formal education was a lost expense. Who could oppose the progress, and cheerful endings of a market economy with full employment, for the benefit of a few? Historically the cartoonist won the battle for often unenforceable legislation, while more than a century later the global war goes unabated in places of business, factories, city streets, and food production. Then as well as now, does the aspiring middle-class child consumer know or care where the latest fad of a must-have toy comes from? bjb