CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

VISITORS ON CITY STREETS

AMERICAN DIARY by BEATRICE WEBB (1898)

Two of the most famous British guests at Hull-House were Fabian socialists Sidney and Beatrice Webb, who visited Chicago in 1898. While Americans were developing their version of the new social sciences based on the measurement of material reality at the fledgling University of Chicago, the Webbs were were on the same track founding the London School of Economics in 1895. The funding came from a bequest to the Fabian Society.

The Fabians were middle-class socialists dedicated to the betterment of society by means of progressive reform not revolutionary change. The Webbs were committed to the ideology that the mental applications of scientific method to define and document the material facts of social life and the role played by government in improvement were the keys to modern reform.

Adverse to emotional displays by crusading Marxists and rallying “working-men’s socialists,” the Webbs’ brand of Fabian socialism privileged a government entitling the well-being of all by means of trained scientific experts–a technocracy of social engineers–in positions of leadership. In Britain, the Webbs were famously active both in the expansion of the social sciences and the founding of the British Labour Party. Beatrice Webb is reported to have named the strategy of “collective bargaining.”

Beatrice Webb was privileged, educated, and elite, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant who made his fortune in cotton. She shared an obsession with Herbert Spencer in the social sciences determining the true laws of society, though she differed with his emphasis on the primacy of the individual and the survival of the fittest.

As a young woman, Webb began writing articles on the working conditions of women in London’s dank factories and sweatshops, at times disguising herself to collect first-hand information. She contributed her investigative skills to a well-received 1888 study, The Life and Labour of the People of London. Webb dedicated her career to scholarly research and collaboration with her husband Sidney.

Her lengthy diary has been transcribed and made available in the public domain. An excerpt of her Hull-House visit in 1898, together with Sidney’s notes on Chicago’s corrupt governance, appear here. Practices in Hull-House offended Beatrice’s British sense of decorum and mental order. The visit made her physically ill, sufficient to cancel the remainder of the American tour and vacation in the Colorado mountains before returning directly to Britain. bjb

“Hull House itself is a spacious mansion, with all its rooms opening, American fashion, into each other. There are no doors, or, more exactly, no shut doors: the residents wander from room to room, visitors wander here, there and everywhere; the whole ground floor is, in fact, one continuous passage leading nowhere in particular ….

[The stay at Hull-House was] so associated in my memory with sore throat and fever, with the dull heat of the slum, the unappetising food of the restaurant, the restless movements of the residents from room to room, the rides over impossible streets littered with unspeakable garbage, that they seem like one long bad dream lightened now and again by Miss Addams’ charming grey eyes and gentle voice and graphic power of expression. We were so completely done up that we settled “to cut” the other cities we had hoped to investigate, Omaha, St. Paul, Minneapolis and Madison; and come straight on here to the restful mountains.”

ARRIVAL IN THE BIG CITY by THEODORE DREISER (1931)

Novelist Theodore Dreiser started his literary career as a newspaperman in Chicago in the 1890s. Unlike many of his journalistic contemporaries, Dreiser was not a refugee from middle-class small town Victorianism who came to revel in the realness of the working-class and the slum. Dreiser also wrote about life on the Near West Side, but it was an area he knew as more than just an observer. Dreiser lived and worked in the neighborhood.

A first-generation American, with a German Catholic father and a Moravian Mennonite mother, Dreiser’s impoverished and often disrupted family lived for the most part in Indiana. At age sixteen, due to instability at home, he set off with a small amount of money from his mother to find his way in Chicago.

His first stop was a rooming house at 732 W. Madison, and he found work a few blocks down Halsted Street as a dishwasher for a Greek restaurant. His often nomadic family soon followed, renting a better apartment near Ogden and Madison, all of them looking for jobs to cover expenses. Instability in employment and in family relations led to frequent moves and income fluctuations, and Dreiser lived and worked in many Near West locations before getting his opportunity at the Chicago Globe, where his innate writing ability soon became apparent.

His realistic style mirrored that of many young writers of the time, but he fell short of the romanticization of a poverty that had been too much a part of his life. His goal and those of his brothers and sisters, Dreiser concluded, was to gather their share of material things, an inclination that led to an aura of immorality around two of his sisters who found that relationships with wealthier men were the key to their uplift.

Much inspiration for his later work came from his youthful days in Chicago, with his most famous novel, Sister Carrie (1901), modeled after his sister’s disastrous relationship with a wealthier married man. Dreiser met an old teacher from Indiana during his dishwashing days. He encouraged him to continue his education and footed the bill for the year of college Dreiser completed at Indiana University in Bloomington. Returning to Chicago, he returned to work as a “collector,” selling cheap household goods and furniture on time door-to-door, and making the weekly collections from the purchasers.

Inspired by the realistic accounts of neighborhood life so prevalent in newspapers of the day, Dreiser took it in his head that his future lay in journalism, but he had no idea how to gain employment at a newspaper. His first job connected with the press was not that of a writer, but as a clerk at a newspaper’s annual Christmas charity, giving away toys to needy families. He eventually was hired by the Chicago Globe, a newspaper he identified as the least successful in the city, and diligently hung around its offices day after day. Eventually he was assigned to the infamous 1892 Democratic Convention held in Chicago, and the quality of his work impressed his editors and sealed his future.

Dreiser left Chicago after working for the Globe for a short time to continue his career in St. Louis and New York. But the several autobiographical accounts that he produced make it clear that his days in Chicago left a permanent impact on his future work. Although much of his description of the Near West Side and other poor neighborhoods is similar to that of his contemporaries, Dreiser was not a mere visitor. He had spent part of his youth within walking distance of the slums he described. The working-class denizens of Chicago’s Near West Side were not as foreign and exotic to Dreiser as they were to many of the other writers of the time. His own family attempted to distance themselves from the masses of poor immigrants of the late 19th century. In fact they were but a step above, maintaining a sort of “genteel” poverty only slightly removed from the slums. bjb

IF CHRIST CAME TO CHICAGO by WILLIAM STEAD (1894)

Chicago grew rapidly in the later nineteenth century. And with that growth came culture but more famously the perils of corruption. Social gospel ministers such as Josiah Strong in the “Peril of the City” (1885) had a field day fuming about the moral unraveling of Christian society, especially in the big city. Moral and religious influence and government were weakest in the big city where they needed to be strongest.

William Thomas Stead was arguably the most talked about British journalist of his day, having made his reputation as an investigative journalist excavating Dickenesque descriptions of the dark realities of industrial urban places. As a publicist aiming to make a difference by influencing public opinion he pioneered a new brand of reform called “government by journalism.”

Stead was attracted to Chicago in 1893 both by the city’s reputation for “great sin” and the 1893 Columbian Exposition with its pretentiously reconstructed ancient Rome and Greece–the White City–from perishable paper and plywood. The progress and humanity of Victorian civilization celebrated in the White City in Jackson Park was nothing better than a flimsy facade. For three months, he wrote, “I was an intensely interested spectator of the rapidly unfolding drama of civic life in the great city which has already secured an all but unquestioned primary among the capitals of the new world.”

Chicago’s West Side as a modern Babylon was ground zero. To orient the reader, a color-coded map of the Levee District located the numerous saloons, pawnbrokers, and brothels with an appendix listing the addresses, proprietors, and owners of the properties. Stead’s goal was to save the “soul” of Chicago from indifferent men of the world. They were administrators, politicians, crooks, and harlots too busy with their carnal, earthly, and devilish affairs to emulate the compassion of Citizen Christ towards the poor, destitute, and needy.

“If Christ Came to Chicago”–what would He think of the pervasive corruption! A clever strategy by which a British political reformer could organize an inflammatory moral and religious tract in which the familiar Chicago response was, “We take no stock of Christ in Chicago.” Allegedly the tract sold 70,000 copies upon publication.

Stead’s narrative excursion which began in the hellish vermin-ridden, putrid dark cells of the Eighteenth-Street Police Station did rise in closing to the light of civic revival in Jane Addams’s Settlement House on Halsted Street, “one of the best institutions in Chicago.”

Led by a humanitarian woman “with a woman’s instinct of natural motherliness,” Hull-House would become a “training ground and nursery” for multitudes of institutions in the great city of the future reconstructing the family and restoring it to health. “The healthy natural community is that of a small country town or village in which every one knows his neighbor, and where all the necessary ingredients for a happy, intelligent, and public-spirited municipal life exist.” bjb

INTESTINES SEEN AT WORK by MAX WEBER (1904)

Max Weber, German sociologist and political economist, visited Chicago for eight days in 1904. The occasion was his participation in the Congress of Arts and Sciences at the World’s Fair in Saint Louis. The same year his only book published during his lifetime appeared, the seminal tract The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. In it he argued that market-driven capitalism, and the bureaucratic-rational-legal nation state coming in its wake was driven by a Protestant ascetic religious calling. The Protestantism ethic produced the superior and rational character-type who pursued the spirit of capital and was marked as the chosen and elect in a society.

In Weber’s view, Ben Franklin with his “character is capital,” and schoolboy homilies–honesty, frugality, hard work–and his role as industrious apprentice printer in the Autobiography was a leading representative of the money economy in the nineteenth century. In Franklin’s artful advice, America’s was a practical and virtuous moral economy.

Weber, however, was not quite ready for his visit to Chicago with its “wild side” of money-making beneath the mere veneer of respectability. With no Franklin in sight, he encountered the primordial, visceral, and predatory quality of common life, from local street vendor to mass production in the slaughter house.

The strongest impressions Weber had of New York City were infrastructure developments–bridges, especially the perspective from the elevated railway over the Brooklyn bridge with the harbors and steam machinery driving elevators. Industrializing Chicago, in stark contrast, was another story, “one of the most incredible cities in the world,” a “monstrous city” his wife called it.

Pollution from soft coal made everything damp, smoky, dirty, and suffocating. It produced eerie halos and impairing sight for more than three blocks in the daytime. A ride down Halsted Street seemed to go on forever mired in congestion, working class tenements, a “pell-mell” of foreign-speaking nationalities, churches, grain elevators, houses of every size from poor to mansions of the wealthy. Blood, slaughter, stench, death, injury, abuse of labor–monetization for profit at every stage of the process– reeked in the massive Chicago Stockyard district.

In the midst of this desert of misery on the West Side, Weber visited the “oasis” at Hull-House, and met Jane Addams, the “angel of Chicago.” Among the elite female reformers, he observed, there was no winking and nodding Poor Richard at work , a disciplined chess-playing capitalist, humanely clever but never deceitful in his calculated moves. In Chicago everything was foreground, unabashedly accessible–in your face.

“The immense city–in area larger than London!–reminds me, except in the mansion districts, of a man whose skin in drawn back and whose insides you may see working. For you can see everything.”

Visiting the new South-western State of Oklahoma, infamous for its frontier violence and racial and religious bigotry, the ever rational and impeccably civil visitor from Germany concluded: “There is more civilization here than in Chicago, and it would be quite erroneous to think that you could behave as you want to.” Both Max and Marianne Weber embraced Western Civilization wherever they found it! bjb

CHICAGO’S MELTING POT: HALSTED STREET by EDITH WYATT (1910)

Edith Wyatt (1878-1958) was a woman of many talents: fiction writer, literary critic, and social commentator. Her father’s work as an engineer working on railroads gave her an understanding of the role of modern transportation systems, and how they were changing rural and urban landscapes. Wyatt was successful writing for popular magazines, McClure’s, Appleton’s, Atlantic Monthly, Collier’s. Her first love was the rural countryside, but she had the ability to settle in Chicago and become a realistic observer and tourist of inimitable urban facades.

Her article featuring a processional ride down Halsted Street capturing in concrete detail and vivid impression the “unmeasurable strength” of street landscapes shifting rapidly with diverse ethnic cultures, religious practices, businesses, and the block-long Hull-House Settlement was an achievement. Wyatt, a lifelong urban tourist with a journalist’s realistic pen, intrinsically understood the density and diversity of inbred human lives with their own personal meanings on Halsted’s gilded street-way. bjb

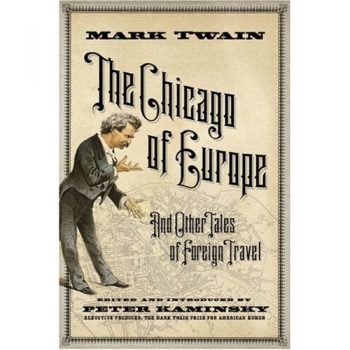

THE GERMAN CHICAGO by MARK TWAIN (1906)

Mark Twain first visited Chicago in 1853, when he first left his family home in Hannibal MO. Eighteen-years old, he traveled from St. Louis to New York City both to find work in the printing trades and spend time visiting east coast cities. In the period Chicago was on the cusp of major growth, accelerated by the expanding role of the Mississippi River as a major north-south transportation route, and the decline of St. Louis as a port in a slave-holding state.

After the War in 1868 Twain wrote travel letters to The Chicago Daily Republican, and then returned to Chicago between 1869 and 1871 on successful lecture tours. The Chicago Daily Tribune covering Twain the lecturer and performer, wrote on November 21, 1869:

“Mark Twain’s lecture in the Music Hall last evening was very favorably received by one of the largest audiences of the season, and those who went … primed for merriment were in no wise disappointed …. His stories and illustrations are strikingly original and unique, and provoked hearty laughter and the applause they deserved.”

In 1879 at a three-day veterans’ reunion honoring General Grant in Chicago, Twain was a featured speaker delivering the toast at the banquet. His irreverent remarks, “To the Babies,” were widely reported in the press. Over the years Twain had a number of business dealings requiring visits to Chicago, including the Paige Typesetter failure. He also came through Chicago when taking his family home to Keokuk Iowa.

In 1893 he visited the World’s Fair in Chicago. The Fair’s World Congress of Religion attracted great interest, and when he visited India he discovered people who thought Chicago was a holy city. He corrected the mistaken idea in a maxim in Pudd’nhead Wilson. Satan told a new arrival to Hell: “The trouble with you Chicago people is, that you think you are the best people down here; whereas you are merely the most numerous.” Twain then doubled down: “When you feel like tellin a feller to go to the devil — tell him to go to Chicago — it’ll answer every purpose, and is perhaps, a leetle more expensive.”

Twain’s keen literary eye probed the murder mystery plot embedded in most everything he thought and wrote. He presumed that lawless even criminal intent lurked in everyone. He viewed the liberal claim that the steamboat, the railroad, the newspaper, the Sabbath school were the van-leaders of a progressive civilization in the upper Midwest as whimsical romance. In Twain’s reality the whiskey dealer took the lead, followed by the “tomahawk of commercial culture sounding the war whoop of Christian culture.”

Chicago’s growth from a frontier town to a major industrial center was so rapid over the four decades of Twain’s familiarity with the city that he wrote in closing Life on the Mississippi:

“We struck the home-trail now and in a few hours were in that astonishing Chicago–a city where they are always rubbing the lamp, and fetching up the genii, and contriving and achieving new possibilities. It is hopeless for the occasional visitor to keep up with Chicago–she outgrows his prophecies faster than he can make them. She is always a novelty; for she is never the Chicago you saw when you passed through the last time.”

Twain later called Berlin the “German Chicago” for its dynamic change and novelty of development resembling the Midwestern metropolis. bjb