CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

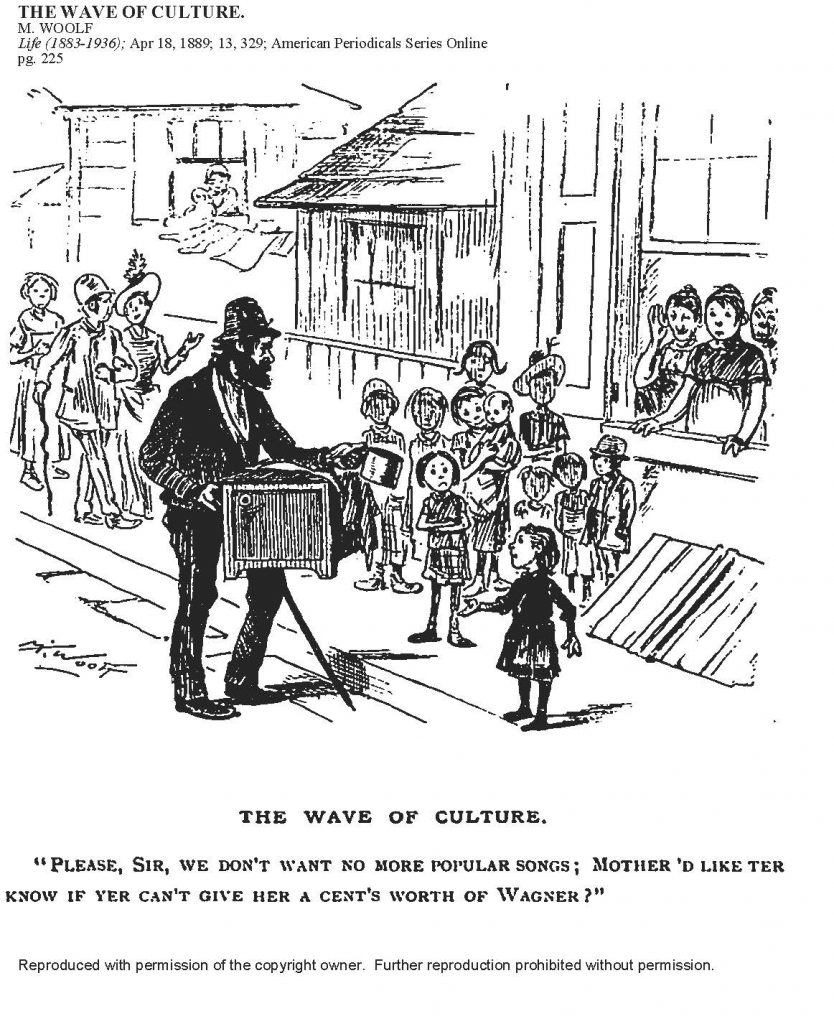

POPULAR MUSIC

The sounds and evidence of music appreciation and music education, both sacred and secular, were everywhere on West Side city streets. Italians gesticulated when singing Neapolitan songs, Talmudic male Jews swayed and chanted fingering their shawls and repeating the commandments, peddling criers rhythmically shouted out their wares from wagons. Walking the local streets, Theodore Dreiser observed that the “accordion, the harmonica, the Jews Harp, and the clattering tin-pan piano or stringy violin were forever going.”

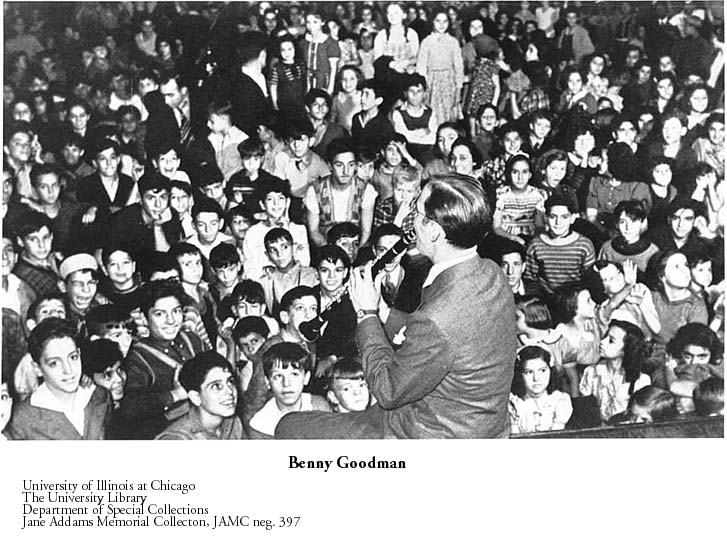

The band leader, Benny Goodman, learned his music in the local synagogue, adapted it in Hull-House, and incorporated the jazz of Chicago’s African-American beat and rhythm to produce a fresh ballroom sound for the increasingly popular and swinging dance floor.

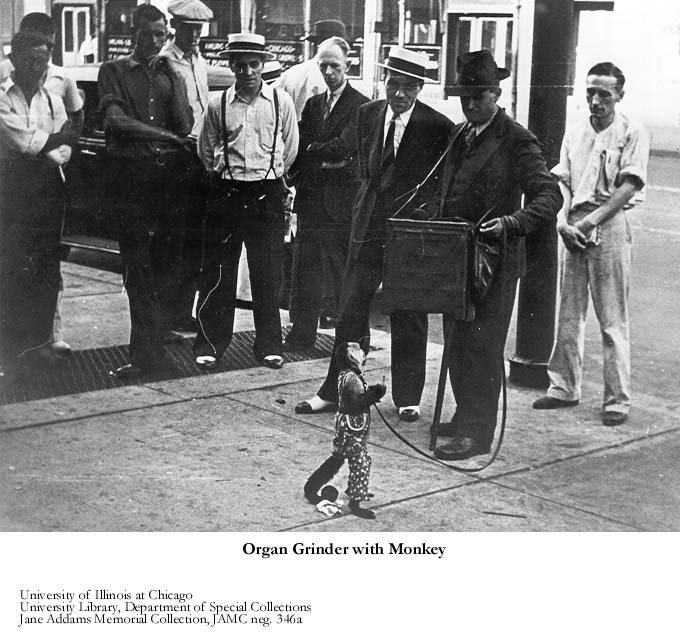

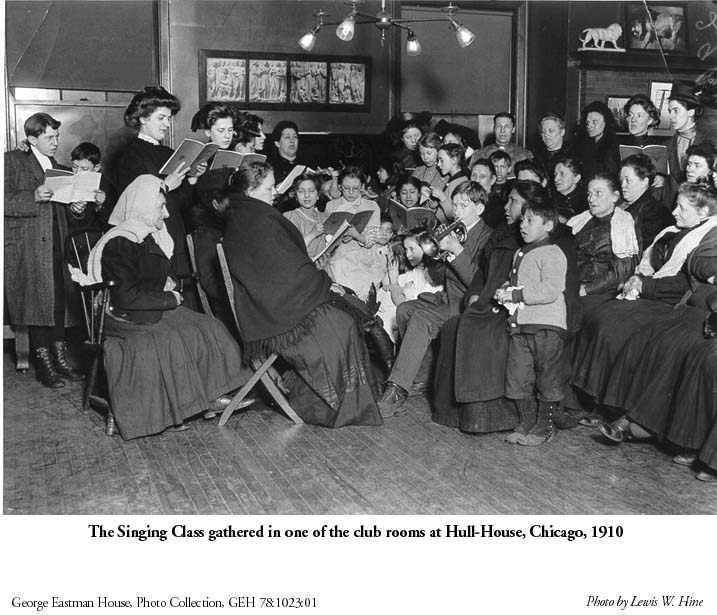

Sheet music sold in shops, the organ grinder entertained crowds of children, pianos furnished some tenement apartments, women and children bundled up in warm garments came from off the cold street into Hull-House for singing sessions. Lessons in instruments were among Hull-House’s more successful programs, as witnessed by the photograph eye of Lewis Hine of the young Jewish boy and his immigrant Russian-Jewish teacher.

Music teachers and musicians had a history of piecing together a living, crossing boundaries between private lessons, classroom teaching, church choirs, organs, special family events, music halls, nickelodeons, theater, and vaudeville. The majority filled in the gaps between gigs by working as sales people and vendors in street businesses.

Even when employed only part-time, women and men in the district identified music as their primary occupation for the federal census. Though poorly paid, more women identified as music teachers than school teachers, the next largest group. In the professional class in the census, there were nearly as many musicians and teachers of music listed as all other professionals combined. Pride, pleasure, and the dignity of a skill were speaking in a diverse and changing inner city slum and ghetto.

Every nationality, ethnicity, and race identified with, adapted, and promiscuously shared the musical sounds of a heritage. Disturbing “noise” to the classically trained college-educated ear was the inviting sound of nourishing soul-food transcending the diversity of bickering cultural prejudices. bjb

INTRODUCTION

PHOTO GALLERY

- Hull-House Boy’s Band

- Benny Goodman at Hull-House

- Music at Hull-House

- Music On The Street

- Off The Street Music Groups

KING OF SYNAGOGUE SWING: BENNY GOODMAN

- Benny Goodman (1909-1986)

- Benny Goodman and The Hull-House Boy’s Band

- Music In My Hand by Benny Goodman: Chapter 1 Autobiography

- Scuffling by Benny Goodman: Chapter 2 Autobiography

SURVIVAL ON WEST-SIDE STREETS: MAX THOREK

STREET ORGAN GRINDERS (1900-1911)

- Blow at the Organ Grinder, Ordinance Curtailing Privileges of Itinerants (1900)

- Organ Grinder a Success In Business (1904)

- Train Boys As Monkeys (1904)

- Girl Is Missing, Gypsies Sought, West-Side Organ Grinder (1911)

STREET MUSIC AND MUSICIANS: JANE ADDAMS ON REFORM

- Street Music and Musicians by Jane Addams (1909)

- See Music and Music Education at Hull-House: “Oasis” in a Slum