CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

MAXWELL STREET MARKET

From the 1880s, Eastern European became the dominant ethnic group on the east-west streets intersecting Halsted just south of Rooselvelt Road (12th St.). An impromptu ghetto market of Jewish pushcart peddlers and street vendors first appeared open only for business on Sunday, after the Jewish Sabbath.

In 1891 the Chicago Tribune observed, “Every Jew in this quarter who can speak a word of English is engaged in business of some sort. The favorite occupation, probably an account of the small capital required, is fruit and vegetable peddling. Here, also, is the home of the Jewish street merchant, the rag and junk peddler, and the ‘glass puddin’ man. The big rag warehouses and scrap iron yards are here supplied by the decrepit old rag pickers and the noisy owner of the ‘old rags an iron’ wagon.”

What followed was an open-air flea-market including retail stores that prospered in the hey-day. The street market encompassed nine square blocks centered at Halsted and Maxwell St. (1330 South between 13th and 14th St.), from 12th to 16th Street. The area expanded in size spreading along Jefferson St.

Customers in the market were largely recent immigrants. Most anything they needed or wanted could be bought at a lower cost in the ghetto market than elsewhere in the city–where they usually were unwelcome. Everything was available for a price. The Jewish market was a magnet. Early customers were Slavic peoples, Italians, Greeks, Germans, later Asians, Mexicans, and African-Americans recently arrived from the rural south.

Photographs inside local tenement apartments display the range of goods immigrants were purchasing including basics such as napkins, table clothes, utensils, and ordinary clothing. At the more elegant end of purchases were china plates, decorated wall paper, and brand-name suits and dresses for religious and family events, including taking the mandatory family photograph at a local studio .

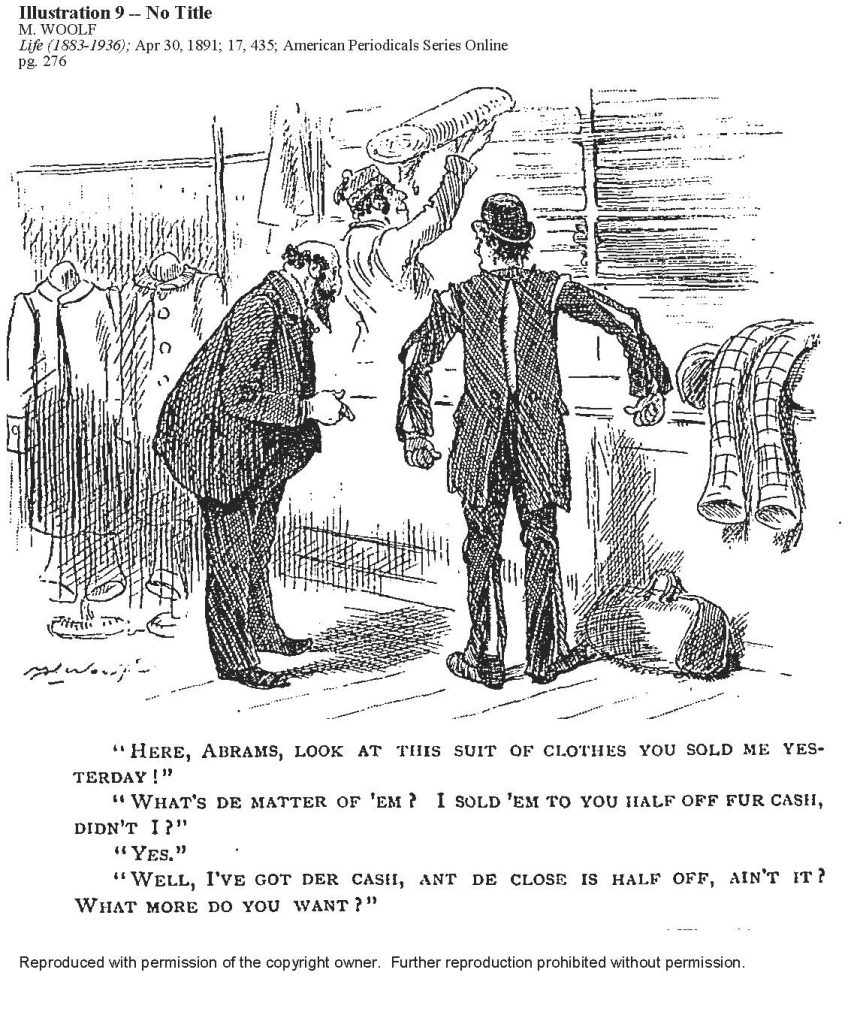

The Yiddish motto on the street was “We Cheat You Fair.” Cash or “gelt” was king–green a shared color–by all the diverse nationality, ethnic, and racial groups, despite each harboring their divisive legacies of intolerance. There were no angels in the market but there were “good deals.” The attraction for everyone in this “emporium” were the bargain prices, due to low overhead costs and the moving of surplus inventory purchased by jobbers at substantial discounts from main-line manufacturers and retailers who were disadvantaged by fixed high carrying costs.

The cheap economy on Maxwell St. functioned both for vendors and for consumers to address income inequities between rich and poor. The capital-driven manufacturing system–domestic in 1900 and increasingly global in 2000–significantly overproduced inventory. It also imperfectly predicted or timed consumer demand. Surpluses remained to be sold off. Prices–“how much”–were on everyone’s lips. Customers furnished their own delivery services. State Street department store unsold inventory regularly appeared on tables and racks in West-Side jobber shops.

Vendors could sell fifty percent of a lot of goods purchased at which price-point they made back initial costs. The remainder fifty percent was now pure profit. What followed was a methodical process of bargaining and lowering the price to receive value from every last unit.

It is estimated that in the years before 1920 Maxwell Street was the third largest grossing retail district in Chicago, after the Loop, and Halsted and 63rd St. (Cash businesses routinely did not keep detailed records, if any at all, for the tax man.)

Contrary to historians who view Maxwell Street as a throwback to an old-world market town, the stocking, distribution, and turnover of goods in the ghetto market were innovative in U.S. economic history. A line can be drawn from Maxwell Street to Sam’s Club or Costco, including Amazon and the online dollar discounters. These corporate distributors currently dominate the U.S. consumer market where prices fluctuate greatly, even daily, for competitive advantage. The manufacture’s “unit price” designated for every product from automobiles to oreo cookies is a fiction, a ploy by marketers to mystify the consumer seeking value.

INTRODUCTION

- Evolution of The Maxwell Street Market by Stephen A. Brown

- Evolution of The Market Street Market Notes

PHOTO GALLERY

The many contemporary photographs of shoppers coursing along the densely crowded Maxwell Street were telling. Middle-class sensibilities were accustomed to spatial order and decorum, and the domestic home-like atmosphere in such department stores as Marshall Field, Carson Pirie Scott, and Montgomery Ward in the downtown Loop district along State Street.

In the Maxwell street photographs, what appeared to gentlemen and ladies nurtured in decorum and manners to be a mob jostling for position, making body contact, and physically handling the goods was not personal assault, insult and harassment. Public space in the Maxwell street district functioned with more intimacy and informality than on north State Street. The rhetorical currency in business transactions was candor not polite euphemism. The customer was not always right, or at least the talk was always open to a haggle.

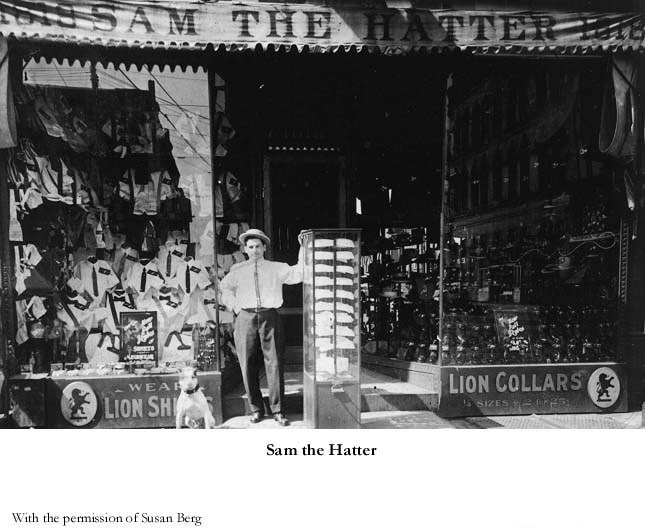

Shopping on the market street was relatively orderly with a hierarchy of vendors and their inquisitive customers moving along in settled lanes. Most lowly were the peddlers with their flimsy carts set up on the street-side of the curb. Adjacent to them were the vendors on the outer curb of the sidewalk with more permanent fixtures and places. Store Fronts with display windows on the inner sidewalk were the most enduring and permanent establishments for repeat business. Overlooking the street in upper stories, residents lived in tenement apartments.

It was a familiar even friendly way of life for families–men, women, and children–on the West Side. It came with its own set of values and daily conveniences. Moreover it was difficult to explain to the well-to-do monied folk, especially club women avoiding any word or gesture attracting the wrong kind of street attention, who patronized State Street retailers and subscribed to home delivery services after a shopping excursion. bjb

MARKET BUSINESS (1895-1929)

The market was officially recognized by the city in 1912, when it became more regulated and politicized, for example by the imposition of licenses. Among the contentious issues between parties were the rising cost of rents, fluctuating prices for goods and commodities, the accusation that stolen goods were being fenced, the powers of the market Master, the labor of children, and more. After 1920, most businesses continued to be Jewish owned but the residential Jewish population began moving further west to the suburbs. The West Side was a gateway or portal to the city, and African-Americans, Mexicans, and others began moving in. By the later 1920s, when Lewis Wirth at the University of Chicago researched his classic, The Ghetto (1928), the first period of the Jewish market was coming to an end, and its spatial dimensions downsizing. bjb

- An Oasis In Maxwell Street (1895)

- Pool To Sell Meat, Butchers Raise Prices Fully Fifty Percent (1895)

- Tons Of Stolen Junk (1895)

- Buy Much For A Penny (1896)

- Cut In Bread Prices, Cheap Loaves Sold in Poorer Districts, Quality Disparaged (1898)

- Raid The Sidewalk Merchants, Maxwell Street Police Raid (1901)

- Marketing In Chicago Ghetto (1901)

- Mad On The Census Man (1910)

- Sidewalk Market In The Heart of the West Side Ghetto (1911)

- Seek To Enjoin Market Master, Peddlers Hire Lawyer (1913)

- Boost In West Side Hair Cuts Causes Two Riot Calls (1914)

- Cheap Markets Need Of Ghetto (1913)

- Peddlers Accuse Market Master (1913)

- Scene In Maxwell Street Market on a Sunday Morning (1913)

“Pullers”: Market Vendors

Pursuing prospective customers, the “Puller” literally crowded and blocked shoppers walking on the street looking to pull them into the store. Always a male, he talked voluminously from a routine script with an exaggerated sales pitch about the great bargain on high quality products–usually personal garments, shoes, wearing apparel– awaiting the lucky “target.” More successful stores employed a full-time puller but most were part-timers. The work paid well. Salesmen and pullers were members of a local labor union, The Chicago Retail Clerks Association, affiliated with the A.F. of L. bjb