CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED, A “WELL-REGULATED CIVILIZATION”

Promoted by city planners and architects, The City Beautiful Movement took off in the 1890s and early 1900s. Architect Daniel Burnham in Chicago who designed the 1893 “White City” and later the “Plan for Chicago” was closely identified with the movement. The philosophy directed practitioners to redraw the map of rapidly growing cities by designing an aesthetic of beauty drawn from neo-classical conventions. Proposing to eliminate “the general smudge in which we work,” the movement emphasized an enlightened order and the aesthetics of harmony to rid cities of pervasive urban ugliness.

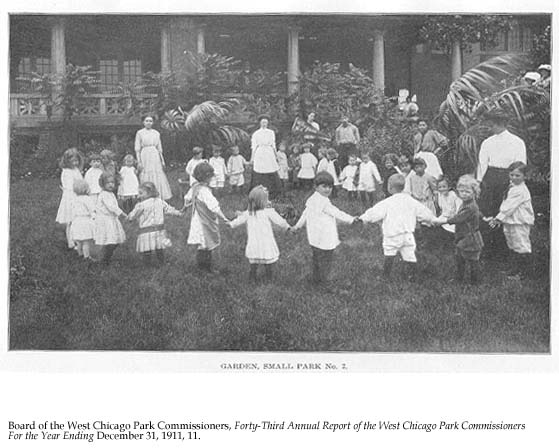

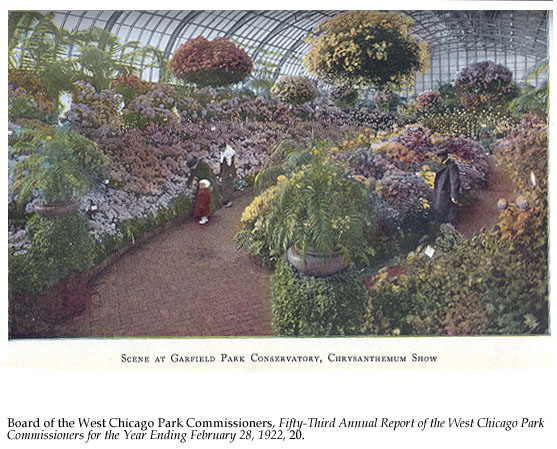

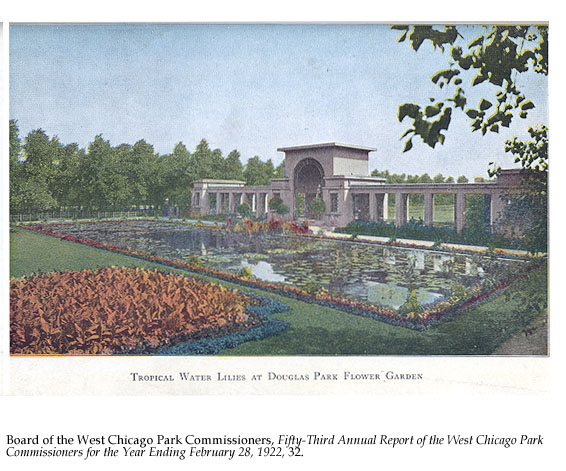

Beauty in the urban designer’s aesthetic came alive in symmetrical forms pleasing to the eye, agreeable to the senses, and monumentally grand. With a presentation of colorful drawings, the City Beautiful appeared in scrupulously landscaped parks and gardens, in integrated transportation grids synchronized with broad green-belt boulevards, in picturesque neo-classical buildings, and in stately strategically located museum repositories of “civilization.” No poverty was visible.

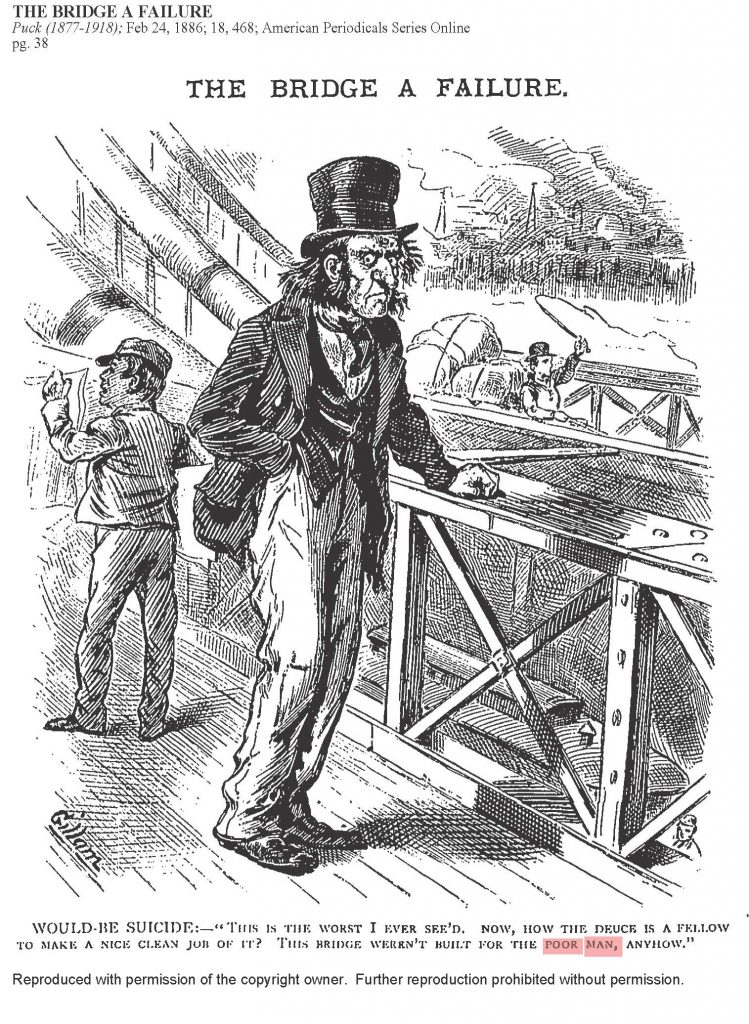

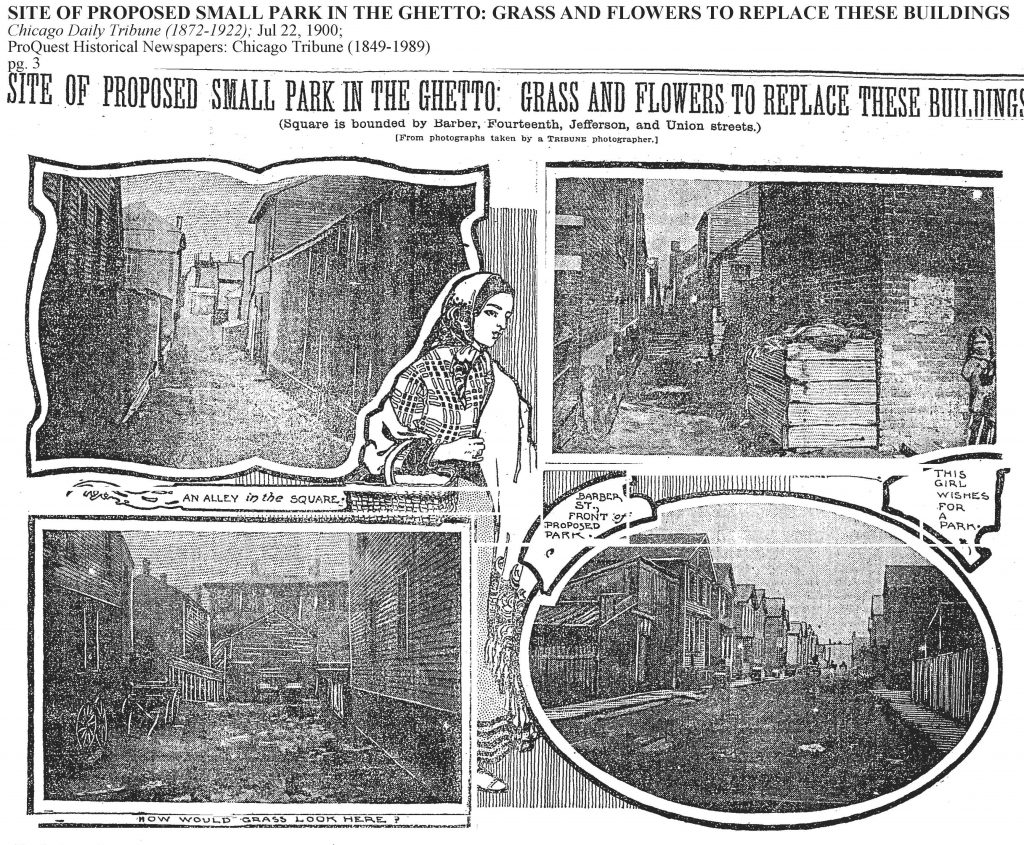

Reformers were viscerally disgusted by wretched and foul conditions. Private lives in the modern industrial and segregated city were swamped by dirt and garbage in the streets, alleys, and narrow passageways of slum tenements. Influencing how citizens would think about cities in the future, The City Beautiful Movement cast itself as an engagement in participatory politics. Exposure to beauty in the built-environment would liberate urban citizens for democracy.

Beyond a pure architect’s aesthetic in picturesque illustrations, beauty in the new city assumed the superior teachings of an educator’s morality. The City Beautiful would uplift the masses out of the darkness, poverty, crime, and chaos characterized by Chicago’s West Side slum. It would raise citizens to the the level of dignity associated with engagement in shared civic beauty and public service. bjb

INTRODUCTION

PHOTO GALLERY

CITY BEAUTIFUL: WEST SIDE (1901-1913)

Dream, delusional, fanciful, impractical, staggering were among the objections to Daniel Burnham’s architect drawings centering the city on the lakefront with a grand boulevard from Grant Park to Halsted Street, end of the line.

Not all local residents bought into the City Beautiful restructuring plans to move the train terminals eliminating the West Side “portal” to the city which included the ghetto as a busy and active business district at Maxwell Street and Halsted.

Among the responses: “Why should the people be compelled to accept [these plans] just to please a few real estate gamblers and some lovers of the arts and the classics.” Facetious and satirical: “As I saw the beautiful pictures of the city beautiful we will have fountains in west Madison Street, with poets and poetesses walking along Clinton, and the simple-minded residents of the west side, after work is done, will take their gondolas and row on the limpid bosom of the Chicago river, idly strumming guitars.”

Except along the beautified lakefront, Michigan Avenue, Lake Shore Drive, and pockets of gentrification–a “city practical” with all its blemishes, warts, and “alien” peoples indeed prevailed for the remainder of the century, expanding outward into neighborhoods west, north, and south. bjb

- Begin to Judge Flower Gardens (1901)

- Suggests West Side Plaza (1908)

- Utility Opposes ‘City Beauty’ (1908)

- A City Beautiful or A City Practical-Which Shall It Be? (1910)

- Board Boosting City Beautiful (1911)

- Sample Gardens in Public Parks For City Farmer (1913)

- Fable and Dream (1913)

- See Maxwell Street Architecture Tour

CITY BEAUTIFUL (1900-1913)

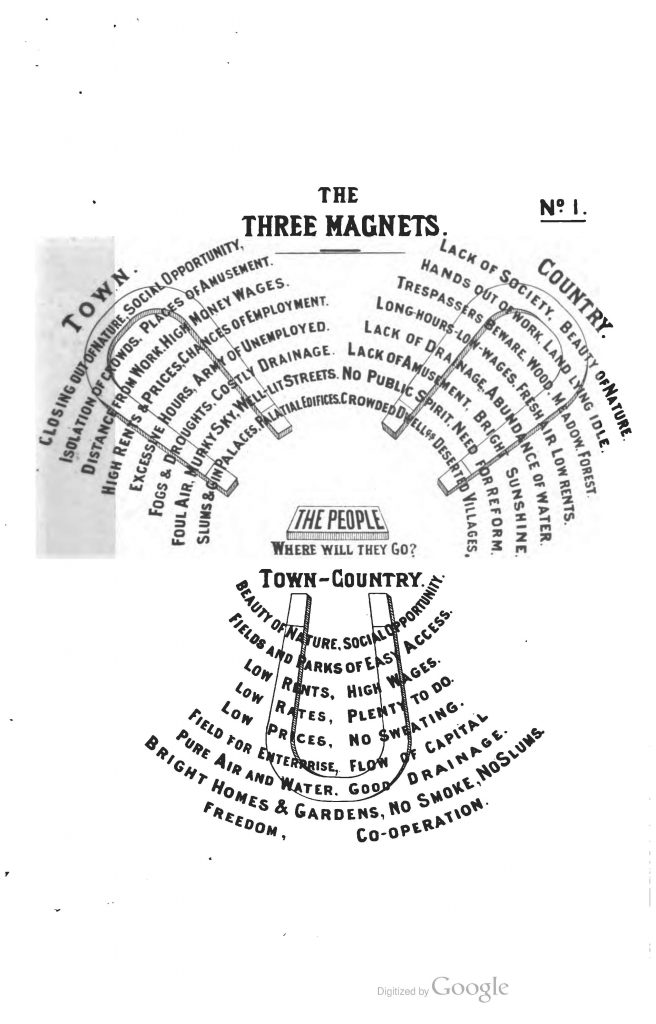

Animating the City Beautiful Movement, Ebenezer Howard in 1902 published a utopian vision, Garden Cities of To-morrow. The inspired tract graphically laid out and illustrated the aspirations of a new civilization, plotted to eliminate friction between capital and labor, countryside and town. The city, with affordable rents and independently managed by the residents themselves, was designed for a domesticated beauty harmonizing “town” with spaces free of slums, overcrowding, poverty, toxic air and infectious diseases within belts of natural green-belt environment with fresh air, beauty, and health.

No beneficiary of privilege or nobility, Howard was the son of a baker and served out his time as a modest clerk in a long career as a British civil servant. However, the original impression for his visionary green cities tracked back to the U.S. and specifically Chicago where he lived in the 1870s. He had first migrated to Nebraska in the post Civil War year of 1871 where he failed as a farmer, then resettled in Chicago working as a stenographer and reporter for the courts and newspapers before returning to Britain in the later 1870s.

During these seminal years of personal formation in the U.S. Howard acquired an admiration for American poets Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was infected by their passion for minimizing the alienation of human life and improving the quality of material and spiritual society through the essential truths of nature. Subsequently Edward Bellamy and Henry George, best selling free-thinking American visionaries and critics of capitalism’s material greed, shaped Howard’s “suburban” model for a city plotted to integrate function and beauty.

In “to-morrow’s” twentieth century from the perspective of 1902, planned cities harmonizing landscape beauty and practicality in residential living assured the future of enlightened living. bjb

- Garden City of To-Morrow by Ebenezer Howard (1902)

- Parks, Boulevards, and Their Influences (1900)

- To Make a City Beautiful, Daniel Burnham (1902)

- Plans For a City Beautiful; Chicago Not Last in the Race (1907)

- Plan For City Beautiful (1908)

- Gardens in Windows, on Porches, in Dooryards…Chicago the Real City Beautiful (1909)

- Nature Experts in Demand…City Beautiful (1909)

- The Call of The New City (1913)

HOUSE BEAUTIFUL (1878-1920)

Furnishing the proper home and behaving correctly in the House Beautiful became a popular theme in a proliferating number of nineteenth-century American advice books, manuals, and magazines antedating the City Beautiful movement.

From 1844 to 1903 an evangelical magazine, The House Beautiful, preached that the home was a spiritual temple. Material representations of artistic beauty were godly. In The American Woman’s Home (1869), Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe dedicated a chapter to beautiful and tasteful furnishings in parlors–the family room–as the vessel for wholesome Christian soulful living. Moral and spiritual truth resided in good taste displayed by families aspiring to refinement and enlightened respectability in America.

Clarence Cook’s articles in Scribner’s Monthly in 1877 on home furnishings, collected in The House Beautiful (1878), served as a standard reference work for an expanding well-to-do middle class. Popular magazines with a modern message and lavish advertising for home products now appeared: Ladies Home Journal (1883) reaching one million subscribers in 1903; Good Housekeeping (1885) with a circulation of 300,000 in 1911.

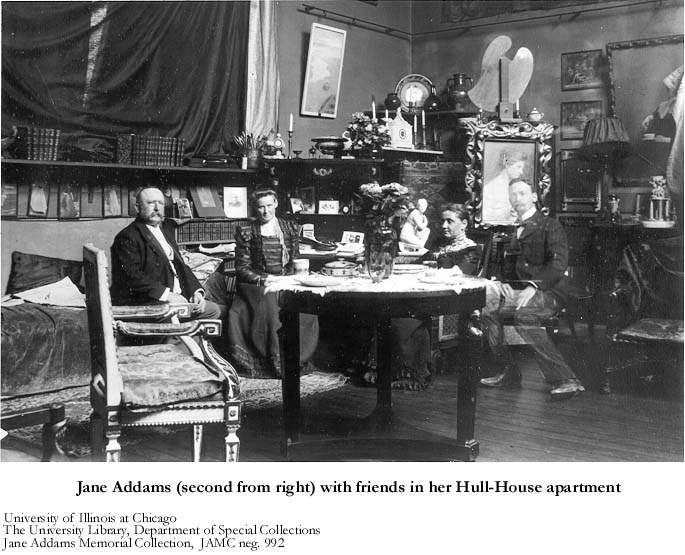

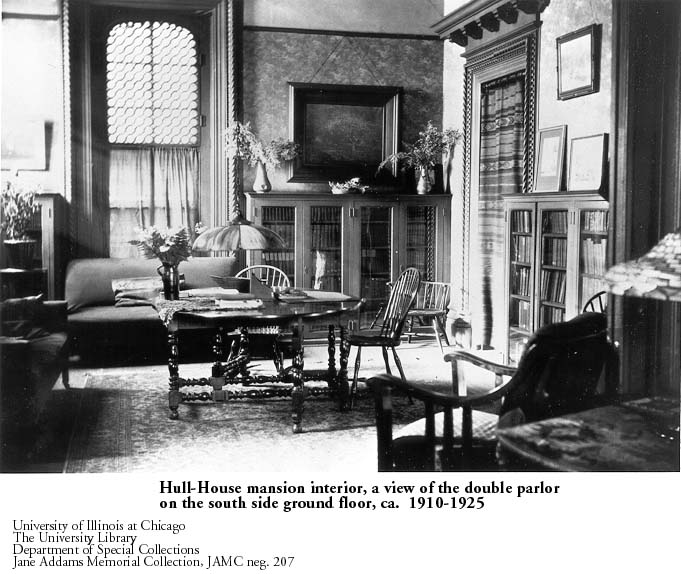

In contrast to the “ugliness” outside on Halsted Street, multiple art and craft objects adorned the rooms, mantles, and walls inside Hull-House. The Arts and Crafts Movement in Chicago was founded at Hull-House in 1897 and supported traditional craft skills practiced by diverse ethnic nationalities. Believing that industrial capitalism degraded the life-giving spirit of human endeavor, advocates promoted the interaction of art and labor embodied in moral regeneration through craftsmanship.

Hull-House both provided training and displayed the handicraft arts of weaving, ceramics, book-binding, and wood working. Frank Lloyd Wright delivered his landmark “The Art and Craft of the Machine” to the Chicago Arts and Crafts Society at Hull-House in 1901. Wright cited leading spokespersons, William Morris and John Ruskin, who worked to elevate the aesthetic tastes of industrial workers by means of contemporary craft designs. He observed in conclusion that “the essence of this thing we call the Machine … is no more or less than the principle of organic growth working irresistibly the Will of Life through the medium of Man.”

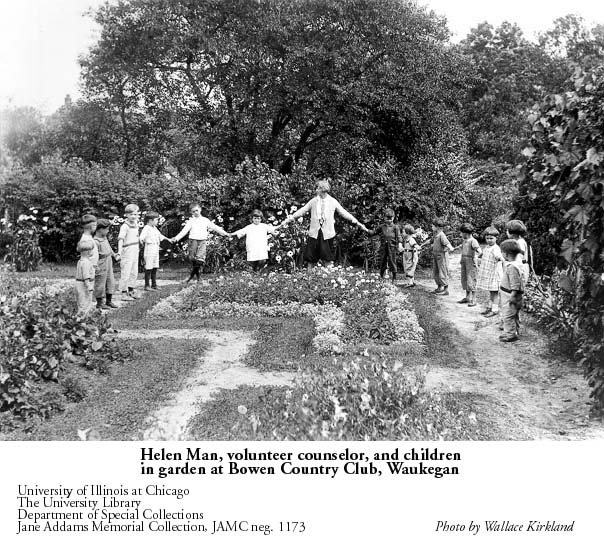

At Hull-House enveloped by the ugliness outside on Halsted Street, Jane Addams associated the aesthetics of the beautiful with “the fittings of a well-ordered life and the surroundings which are suggestive of a participation in the best of the past.” Children needed to be exposed to the “best” a higher civilization offered. “A child cannot be brought up in the midst of what is ugly and dirty and grimy and be the best kind of child. It is impossible. Aesthetics lie close to education and morality.”

Among the educated reformers sheltered in cloistered spaces, Jane Addams condemned the “ugliness” of neighborhood streets as a primary cause of disorderly habits and moral retardation in West Side children. From her perspective, immigrant girls on the street competed by showing off their garish and “ugly department store hats.” Rowdy boys lived out their fantasies of illicit adventure, misbehaving on the streets after imbibing the interminable wacky action in cheap storefront movie theaters.

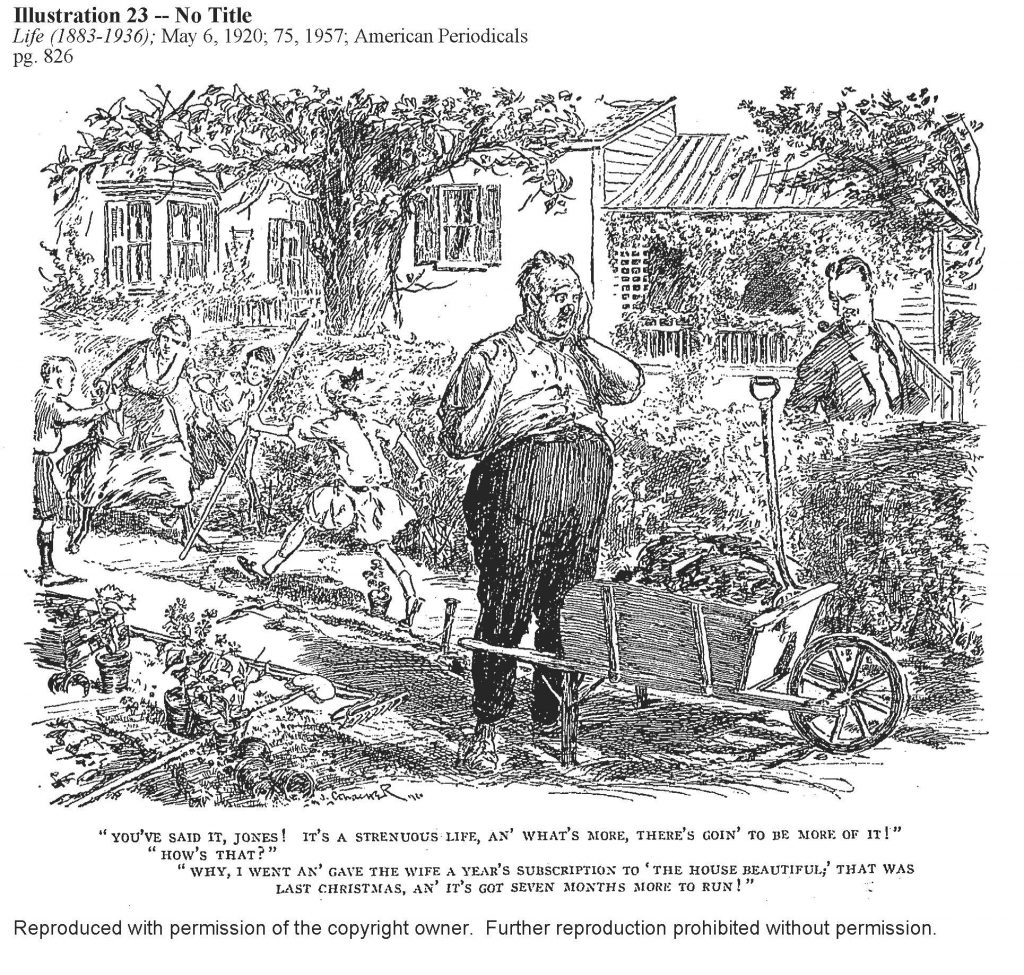

Reformers presumed that affordable publications with “how-to” tips and recipes for beautification of the home for working classes of “moderate incomes” would succeed in elevating moral behavior. bjb

- The House Beautiful by Clarence Cook (1878)

- House Beautiful: Words For the Homemaker of Limited Means (1897)

- House Ornamental: The Brick Beautiful (1903)

- House Ornamental: The Handmade Kitchen Beautiful (1903)

- Hull-House Domestic Interiors: Gallery

GARDENING IN CHICAGO, THE GARDEN CITY (1903-1910)

In the 1830s, Chicago–a swampy outpost burdened by clay soil, severe winters and strong winds–began gratuitously to adopt the name “garden city.” In fact, an abundance of regional prairie plants and seeds together with local truck farmers delivering their products to the city’s west-side wholesale markets did make for a central produce hub of national importance. In addition, backyard and front yard gardeners working to decorate their local street residences; broad green-belt boulevards with lush vegetation planted in the median; even immigrants committed to indoor nurseries in tenements–all nourished the legacy of an urban botanic verdant place. Designed by landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted, Jens Jensen, and O.C. Simonds, gardens and parks scattered within the city surrounded by a belt of forest preserves–all exalted Chicago’s reputation for enlightened splendor and beauty. bjb

- Gardening Mania Is Much Like Love (1903)

- Chicago Becomes City of Gardens, an Old Nickname (1904)

- Chicago as Farming Center Has 64,000 Acres Vacant (1906)

- Gardening in Chicago (1908)

- Porch Gardens Spots of Beauty…Form Oases in Crowded Districts (1908)

- Garden Scenes in the Actual Life Of Chicago, Transforming Vacant Lots into Veritable Oases (1909)

- Gardening in The Garden City (1910)

- Want To Keep Husband Home, Put Him To Gardening, He’ll be Too Tired to Go Out at Night (1910)

PLAN OF CHICAGO by DANIEL BURNHAM

Whether immigrants or emigrants, nearly all Chicagoans in the massively growing metropolis came from somewhere else. With no roots in the city and socially and culturally fragmented , the majority of the population as a practical matter pursued personal or private interests: finding a job, making and accumulating money, marrying upward, speculating and investing in goods and property, planning a move elsewhere under better circumstances. In contrast, the pursuit of quality of living itself and good works were stated priorities more exclusively limited to well-to-do classes along the lakeshore and in the suburbs.

Necessarily focused on their private concerns and the provisional circumstances of their daily existence, the majority of Chicagoans as a matter of course acquiesced to the insult of filthy air from coal furnaces, water pollution, unpaved and broken streets with transportation gridlock across railway corridors, overcrowding and congestion. Add to the list of afflictions: serious hazards to health, outbursts of class, ethnic, and racial hatred, and the frequent event of labor violence.

To transcend the rough city with its sharp edges, the architect planner Daniel Burnham had a better idea. As he put it, “make no small plans.” Could this new megaton city of nearly two million work for the betterment of all, could it benefit by becoming “well ordered” embracing at once entrepreneurial interests, public works, and individual needs? Burnham’s futurist response was strenuously in the affirmative.. His vehicle was a comprehensive progressive planning document, wedding conventions of the classical past to promises of a designer’s prospective model.

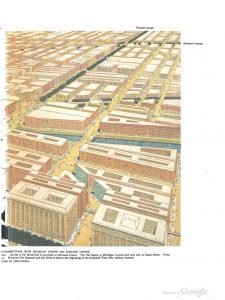

In 1893 Burnham successfully oversaw the design and building of the World’s Columbian Exhibition on the south lakefront, popularized as “The Great White City.” Plaster facades of neo-classical buildings in Beaux-Arts ornamental style, Japanese gardens and Venetian waterways, a fairground (the original Ferris Wheel), and green-belt boulevards–the city of the future worked in practice as an integrated whole within the limited confines of Jackson Park. Astute planning and market savvy made the Exhibition a financial success.

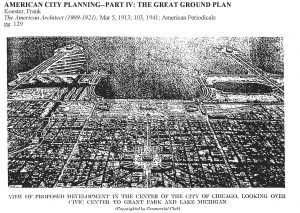

In 1909 “The Plan for Chicago” Burnham laid out on paper the first comprehensive program with controlled growth for the future of a “City Beautiful.” He centered the city on the lakefront and river, with every citizen within walking distance of a park. Chicago would be “The Paris of the Prairie” with boulevards radiating from a domed municipal palace. The effort was noble. However, beyond the sculpted lakefront harbor areas, manicured parks, and statuesque museums it remained on paper, testimony to one architect-planner’s enlightened progressive vision in Chicago. bjb

CITY PLANNING (1909-1913)

With the rapid growth of Chicago expanding beyond the center grid; with the increasing dominance of money-driven private business interests; with the density of working-class poverty concentrated in inner-city housing–an enlightened “city better” became a model aspired to by landscape architects, civil engineers, geographers and public administrators.

Intervention in the built environment became a dominant concern for a new generation of liberal designers and planners. The professional mission was to reverse the blighted consequences of raw sewage on filthy streets, epidemic diseases in crowded tenements, deteriorating health among the working poor, congested transportation routes to city markets, and chaotic neighborhood sprawl.

Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann’s redesign of the capital city of Paris in the mid-19th century with long, straight, and wide boulevards had established an historical precedent. Nevertheless, the evils of urban life for transient inner-city working people in a dynamo-driven industrial city like Chicago, controlled by raw political self-interests, presented a new level of confrontation and resistance to environmental planners and reformers. bjb

- Modern City Planning (1909)

- American City Planning (1912)

- American City Planning-Great Ground Plan (1913)

- American City Planning-Traffic & Terminals (1913)

- Civic Progress in America (1913)

- Freight Depots Most Important In City Planning (1913)