CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

THE BUSINESS OF GHETTO MARKETS

Junk or old and discarded goods regarded as trash and rubbish had real value in the ghetto’s “cheap economy.” Anything thrown away, abandoned, or misplaced, especially by the better-off classes. was finder’s keepers. “That which is rubbish in a backyard,” commented an observer, “becomes merchandize in Canal Street and some lean-fingered speculator converts it into bright money.”

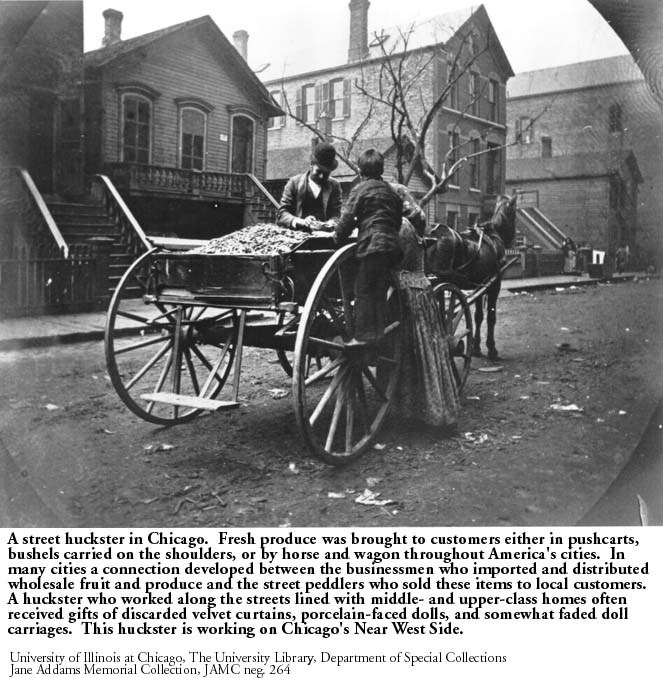

Earnings came in pennies. Nickels and dimes counted. Many immigrants lived on ten cents a day in their first year of work. Hilda Satt did not know any storekeeper who did not live in the back of the store. “Earning a living” were among the first words she learned in Chicago. A reporter observed: “The market on Jefferson Street secures fruit as soon as it gets into the commission houses. They get it perhaps slightly damaged. But they sell it so cheap that the people more than get their money’s worth, even if they have to throw some of it out. The oranges for a nickel are sold three for a dime …. The same is true of every other fruit.”

Profits were in small sales. Bread sold by the half load, and a big pail of beer cost five cents in a saloon. From peddler wagons, potatoes sold for five cents a peck and bananas for five cents a dozen. Overhead costs were kept to a minimum. Staples stored in large burlap bags–rice, beans, coffee, barley–were weighed by the grocer and carried away by the shopper in a rolled sheet of brown paper. Can openers were scarce; grocers scooped out salmon from a large tin can and a shopper precariously walked home with liquid sloshing in a flimsy container. There were seldom shortages, but very little with any additional use-value was discarded.

Fortunes were sometimes made in the scrap business, but that was the exception. Making a living in the West-Side economy was close to the bone, picking up pieces of coal fallen during transport, collecting rags or newspapers or scrap steel parts, rummaging through trash bins for items like broken chairs to sell for a few shekels to a dealer, or collecting old skates and boxes to build go-carts.

There was neither beauty nor nobility in junking, nor Thoreauvian motives of saving the planet by recycling waste. Junk shops were the first places to go for the best prices on small budgets, and a value on savings. Wallace Kirkland’s images of boys and girls junking on local streets testified. It was about adolescent boys and girls splitting up some coins for pocket money. On the street there was a phrase, only the ignorant and gullible buy retail.

The suspicion of junk collectors as thieves, perhaps reselling their booty on Maxwell Street, always lurked in the shadows. Did junking lead juveniles to become “embryonic criminals” or juvenile delinquents–Jane Addams thought so. bjb

BOYS AND GIRLS ON WEST-SIDE STREETS: PHOTO GALLERY:

GHETTO JUNK DEALER & MERCHANT (1895-1909)

“Every Jew in this quarter who can speak a word of English is engaged in business of some sort. The favorite occupation, probably an account of the small capital required, is fruit and vegetable peddling. Here, also, is the home of the Jewish street merchant, the rag and junk peddler, and the ‘glass puddin’ man. The big rag warehouses and scrap iron yards are here supplied by the decrepit old rag pickers and the noisy owner of the ‘old rags an iron’ wagon.” (1891)

- Tons Of Stolen Junk (1895)

- 5000 People Make $5.000.000 Annually out of Junk (1902)

- Deserted Wives in Ghetto, Find Work In Junk Shops (1907)

- Odd Trades in the Ghetto, Men Who Peddle Brooms (1907)

- Peddling Rugs for a Degree, Ambition in the Ghetto (1907)

- Hundreds of Chicago’s ‘Poor’ are Richer than many of Chicago’s ‘Rich” (1908)

- Women as Street Peddlers, Need Widens their Field (1908)

- Junk Road Highway To Riches, Profits Go to the Big Dealers (1909)

- Slum Barefoot Brigade at Work (1909)