CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

STORY OF THE SLUM

“Slum” was a variant pronunciation of slime, an offensive and stinky mess of stewy disagreeable matter. The big-city slum in the industrial nineteenth-century elicited pungent visual imagery, and not a little forbidden imaginative excitement. Dirty and densely crowded back streets and alleys with squalid and wretched low-class living conditions, dangerous places overrun by criminals and wickedness–the image of the “slum” was perversely repulsive as evil and pruriently attractive as exotic to an audience of patronizing citizens.

The act of “slumming” or visiting the slime pits of the inner city often in parties for philanthropic, disreputable, or amusement purposes began happening in the 1880s. Club women and reformers were attracted to the philanthropic opportunities, secret adventures, and illicit attractions in excursions to the nether regions of Chicago’s West Side. bjb

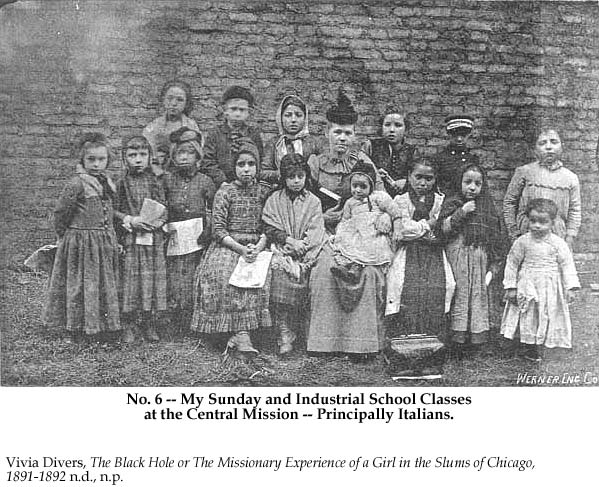

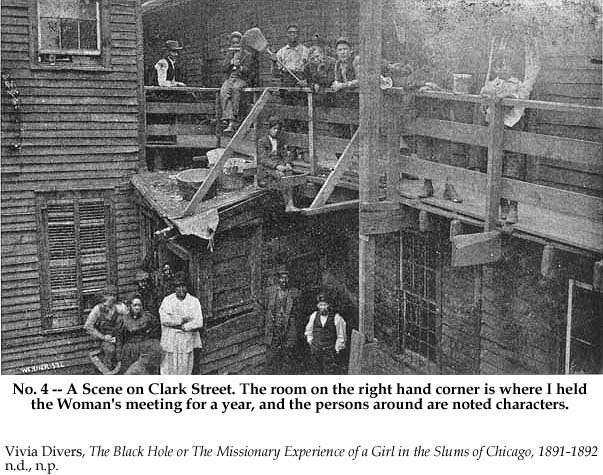

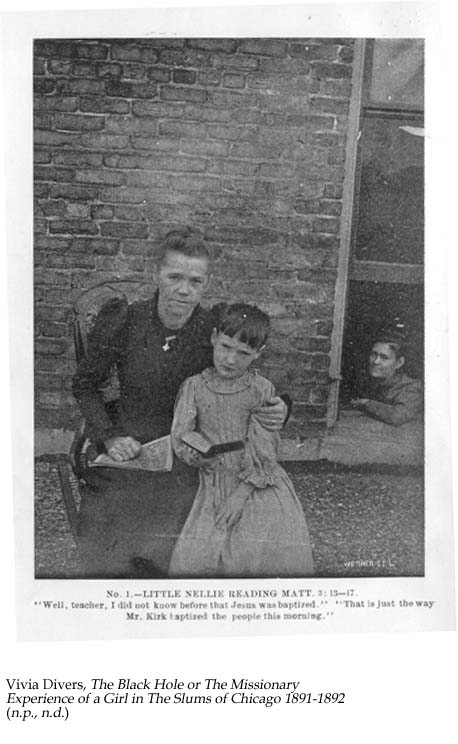

THE BLACK HOLE by Vivia Divers (1893)

Vivia Divers entered the “Black Hole” on a September evening in 1890. Even though the city was already dark when her train pulled into the Polk Street station, Vivia was aware of what she would find. She knew the half-mile square area to be “the most disreputable locality in Chicago,” and home to saloons, brothels, gambling dens and opium joints. Approximately 20 years old, Vivia was a young woman when she left her hometown of Warrensburg, Kansas, to be a missionary in Chicago.

Not much is known about Vivia Divers save the fact that she was a student at The Baptist Missionary Training School from 1891-1892, located at 2144 Indiana Avenue. A charitable institution it competed in its mission with the nearby Hull House. The school trained students for missionary work overseas as well as locally. For fieldwork experience it sent them to evangelize in missions in the Near West neighborhood. Vivia’s assigned district was on Clark Street, between Polk and Harrison, an area “noted for all manner of wickedness: no part of this little strip of one side of a block could be mentioned in which it did not abound.” She describes the ethnic make-up of the district with “Americans, Africans, Italians, Spanish, French, Germans, Swedes, Jews, Arabians and Syrians, – all coming and going, some not staying more than a week or two till they were gone and new ones would come.”

Vivia’s recollections were precise on street names and street addresses. Carrying her Bible and Sunday school papers, she canvassed her assigned area, knocking on doors and looking for “lost souls.” Much of her focus was on the children who “[ran] along the street, with dirty faces, uncombed hair, and clothes almost torn off of them.”

Vivia often reeled at the sights and stenches within the tenement housing. Her descriptions of neighborhood homes were detailed, noting everything from the curtains to the flooring (or lack of) together with particularly bad odors wafting about the people and rooms. Piles of trash, pots of cooking pasta and bad teeth–little escaped her graphic attention. She recounted lengthy dialogues and specific encounters with a variety people ranging from a young Jewish agnostic to a burly saloon keeper. A woman’s murder was vividly described and used as a moral object lesson: “Turn from this life while you have the chance and prepare for the life hereafter,” she plead with the victim’s friend.

Vivia also struggled with the customs and beliefs of various ethnic groups. Frequently the residents would offer her beer or wine as a gesture of welcome or thanks. In response she would decline and reciprocate with a Sunday School temperance lesson.

At one point, Vivia described the process of photographing an Italian family. Mothers believed the camera casting an “evil eye” would harm their innocent children. In this first instance of the use of a Kodak on the streets of the district, Vivia addressed the fears, overcame the resistance, and convinced local residents to permit her to take the photographs, the devil be damned.

The Black Hole is a rare volume. No publisher’s name appears on the title page, not even the name of the author. Almost certainly it was a Baptist religious publication. Its value to the historian rests in the graphically described visitations, both on the streets and inside apartments, often above saloons and whore houses, and Divers’s vivid accounts of the people and their souls in need of her ministry. bjb

PREFACE-TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART 1

- 1-The Trip To Chicago (1893)

- 2-The Black Hole (1893)

- 3-My First Visit In The Slums (1893)

- 4-Mission District on Clark Street (1893)

- 5-First Visit On The New District (1893)

- 6-Industrial School-Business Day(1893)

- 8-Jews & Italians (1893)

- 9-Woman’s Meeting (1893)

- 11-The Sick Woman (1893)

- 12-One Afternoon (1893)

- 13-The Mixed Meeting (1893)

- 14-Another Lost Soul (1893)

- 15-An Inquirer (1893)

- 16-The Italian Sick Man (1893)

- 17-Three Colored Women & Mary Sharp (1893)

- 18-The Drunken Woman Saved (1893)

PART 2

- 1-Thoughts Coming Year (1893)

- 2-One Day’s Work (1893)

- 3-The Pretended Infidel (1893)

- 4-Two Arabian Children-Visits (1893)

- 5-One Stormy Afternoon (1893)

- 6-Grandmother Fountain (1893)

- 7-The Great Physician(1893)

- 8-A Young Woman (1893)

- 9-Among The Italians(1893)

- 10-Our New Friends (1893)

- 11-The Arabian Family (1893)

- 12-She Had Always Been Christian (1893)

- 13-Auntie Smith’s ‘Light House’ (1893)

- 14-Visiting The Children (1893)

- 15-Woman’s Sad Story (1893)

- 16-Organization Black Church (1893)

- 17-An Afternoon (1893)

- 18-At Our Woman’s Meeting (1893)

- 19-The Murdered Woman (1893)

- 20-What Nellie Wright Thought Of Baptizing(1893)

- 21-Two Men(1893)

- 22-Nellie’s Question S.S. Lesson-PSA Li (1893)

- 23-Visit To Nellie’s Home (1893)

- 24-Little Nellie’s Conversion(1893)

- 25-Some Visits (1893)

- 26-Drunkards-Mother & Daughter (1893)

- 27-Scenes On The Street (1893)

- 28-The Rest At Mission Rooms(1893)

- 29-363 & Drunken Woman (1893)

- 30-Our Colored Friend (1893)

- 31-Little Nellie & The Lord’s Supper (1893)

- 32-The Woman’s Meeting (1893)

- 33-Visit To Raymond Mission(1893)

- 34-My Visit To Nellie(1893)

- 35-Mother’s Meeting Bethesda Mission(1893)

- 36-Taking the Picture (1893)

- 37-Nellie’s Baptism (1893)

- 38-My Last Visit On My District(1893)

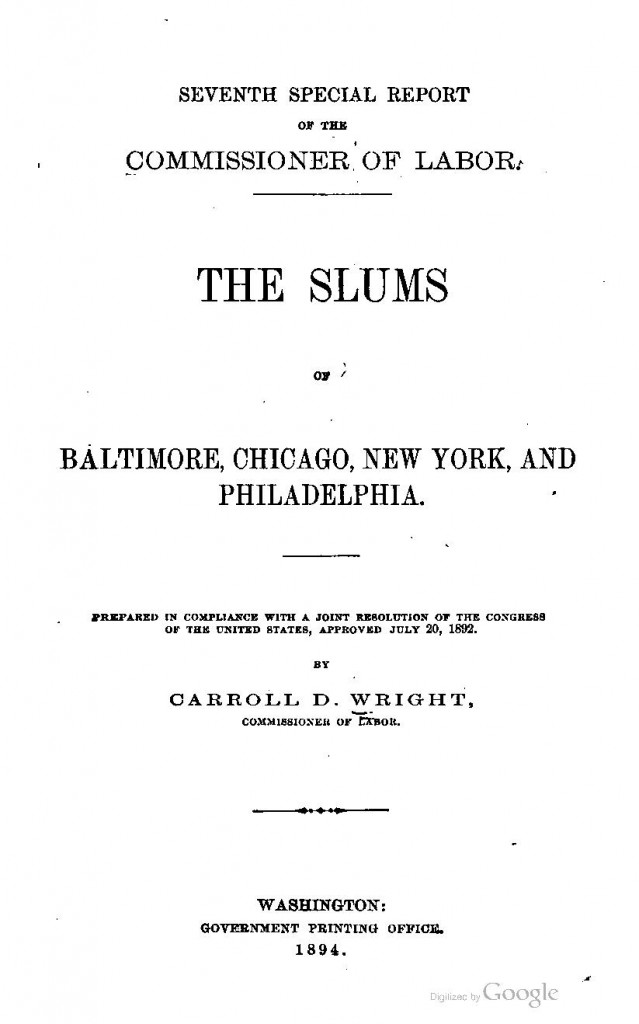

SLUMS OF CHICAGO by Carroll D. Wright (1894)

In 1894, Carrol D. Wright, the first U.S. Commissioner of Labor (1885-1905), in charge of the 11th census in 1890, published a special report, The Slums of Baltimore, Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia. Drawn largely from statistical census information, ti was a six hundred page tome of charts, tables, and numbers. A seminal publication on the topic, it characterized the pathological and dysfunctional behaviors in “slum” areas on selected inner-city streets.

Wright’s relatively unknown classic represented a new critical approach to the definition of an urban “slum.” Addressed to a science educated and enlightened audience, the volume presenting the findings of an investigation by means of statistical patterns and abstracted social categories. The contrast was stark between Wright’s academic approach and the familiar and popular darkly sensual Victorian criminal underworld “slum” of horror, murder and mayhem, a predatory Jack the Ripper and a penny dreadful Sweeney Todd.

Statistics was a relatively new disciplinary language and Wright now led with the “facts” and relatively little analysis. He presumed the numbers patterned in demographic snapshots and averages were now sufficiently riveting, revealing, and instructive without requiring imaginative and melodramatic embellishment.

In the study, Chicago was the only new American city with no eighteenth century venerable east coast origin and location. With the appointment of Florence Kelley, Hull-House actively participated in defining the boundaries of the West-Side slum by canvassing “a square mile extending from Hull-House on the west to State Street on the east, and several long blocks south,” starting from Polk and Halsted, along Taylor to Newberry Avenue to Twelfth to State to Polk and back to Halsted. “In this area we encountered people of eighteen nationalities.” The substance of Kelley’s canvassing for Wright’s statistical volume made possible the innovative graphic presentation of color-coded nationality and wage maps in Hull-House Maps and Papers (1895)

Predetermined streets on Chicago’s West Side now emerged as the mid-western paradigm of a blighted American slum in contrast to more “normal” neighborhoods. On average in the West-Side slum, nearly double the proportion of liquor saloons, double the number of arrests, a large foreign-born and alien speaking population not gainfully employed, males in excess of females with more than twice the number of divorces, laboring children not in school, and dense crowding in deteriorating housing stock. These numbered among the retrograde behaviors and effects documented.

The conservative political economist Wright held out some optimism for the future based upon two positive findings. First, earnings in the representative slum matched other parts of the city, and second no greater sickness prevailed. “The conditions of slum life are not so appalling as they are often painted.” Wright, a critic of the strenuous opponents who stressed only bad consequences from foreign immigration especially from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean, focused his prospective hopes on workers who could be enlightened to the benefits of invention. By which he meant employed workers with skilled trade and literacy skills . They would guide their lives by the “character” values of western civilization.

Wright either ignored the unemployed or expressed disdain. He assumed their plight was caused by their own deficiencies. Despite contemporary labor violence and radical calls for socialist and anarchist action, Wright’s general optimism regarding the economy expressed itself in two essays published the following year in 1895, “The Chicago Strike” and “Have we Equality of Opportunity?” bjb

- See Hull-House Maps and Papers: Presentation of Nationalities and Wages in a Congested District in Chicago (1895)

- The Slums of Baltimore, Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia-Title Page

- The Slums of Baltimore, Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia (1894)

- The Chicago Strike (1895)

- Have We Equality of Opportunity (1895)

HULL-HOUSE MAPS AND PAPERS: A PRESENTATION OF NATIONALITIES AND WAGES IN A CONGESTED DISTRICT OF CHICAGO (1895)

When Carroll D. Wright received funds from Congress to investigate slum conditions in four cities, he turned to the women and residents at Hull-House for the Chicago canvas. Following the example of Booth’s maps of London, the original feature in the Chicago survey became the production of innovative color-coded mappings of polyglot nationalities and impoverished family wages. Displayed in the Hull-House presentation were the canvassing schedules used by the investigators in the congested one-third of a square mile spatial area around Hull-House on Halsted.

Dramatized for public viewing were the intimate details of slum family wages (coded in gold and black), population crowding, and the diversity of eighteen nationalities. The color-coded maps were beyond anything Wright was able to convey in his tome of linear tables, charts, and graphs. Strenuous advocates for a woman’s “helping” profession, the Hull-House social workers did not reach for quantitative purity. Indeed, their mission was to influence public opinion regarding policy prescriptions and legislation to improve standards of living in the “slum” and eliminate the prevalence of sweatshop exploitation and child labor in the district.

“This district was … selected as a slum,” wrote Julia A. Lathrop, “and is that portion of the city containing on its western side the least adaptable of the foreign populations, and reaching over on the east to a territory where the destructive distillation of modern life leaves waste products to be cared for inevitably by some agency from the outside.”

An original reason for the founding of Hull-House was to serve as a saving mission for alien peoples. Noblesse oblige to act with high-minded honor and generosity towards less fortunate ranks was a prevailing sentiment. Driven by an elite philanthropic benevolence towards alien peoples, the Hull-House reformers targeted for their good works simple “peasants” with no agency of their own, “helpless dependents” and “wards of charity.” A dose of condescension, at moments contempt, was present.

Foreign populations were perceived as living “in every sort of mal-adjustment”–peasants without means to organize and cooperate. “Rural Italians in shambling wooden tenements; Russian Jews, whose two main resources are tailoring and peddling, quite incapable in general of applying themselves to severe manual labor or skilled trades, and hopelessly unemployed in hard times; here are Germans and Irish, largely of that type which is reduced by drink to a squalor it is otherwise far above. Here amongst all, save the Italians, flourishes the masculine expedient of temporary disappearance in the face of non-employment or domestic complexity, or both.” bjb

INTRODUCTION

NATIONALITY & WAGE MAPS (1893-1895)

- Wage Map No. 1

- Wage Map No. 2

- Wage Map No. 4

- Nationalities Map No. 1

- Nationalities Map No. 2

- Nationalities Map No. 3

- Nationalities Map No. 4

SCHEDULES FOR SPECIAL AGENTS (1893-1895)

HULL-HOUSE MAPS AND PAPERS (1895)

- Hull House Maps and Papers by Residents of Hull-House (1895)

- Hull-House Maps and Census Schedules

- Agnes Sinclair Holbrook, Hull-House Maps

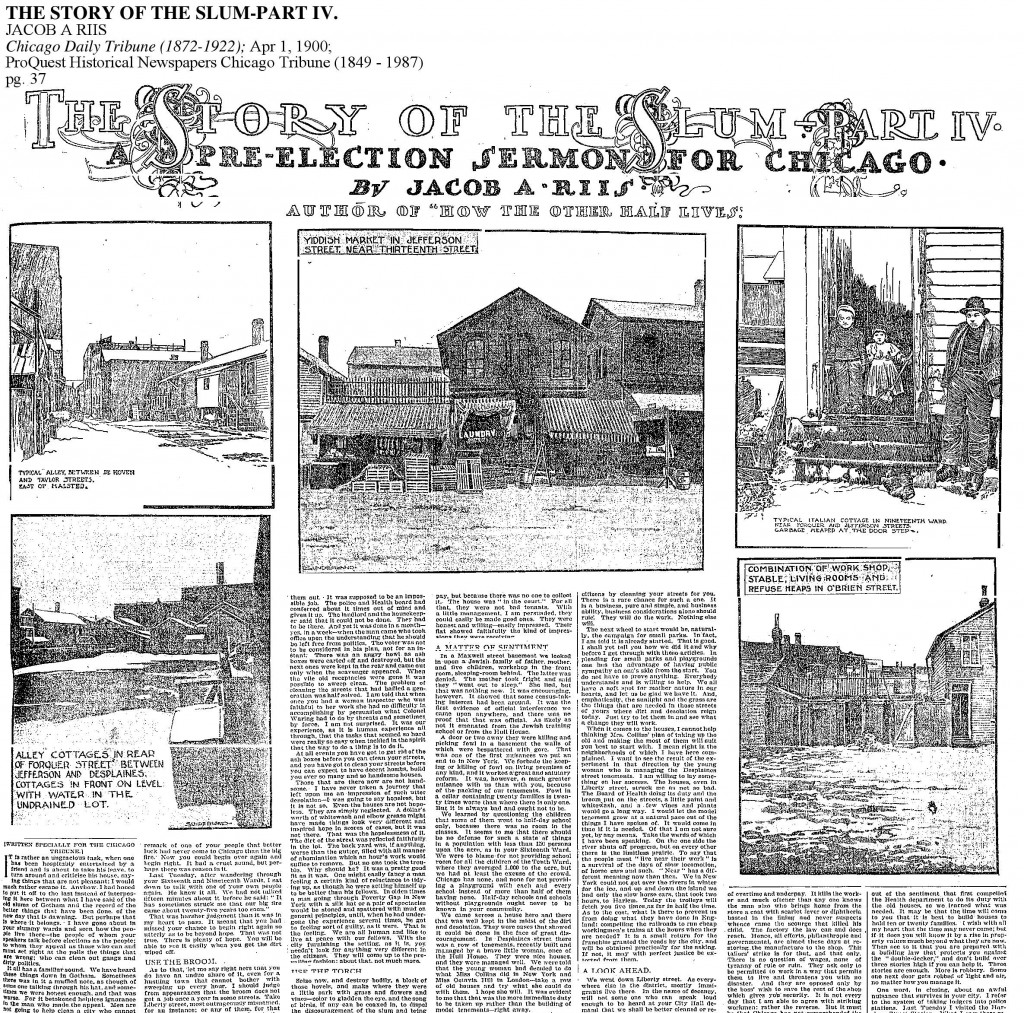

THE STORY OF THE SLUM, CHICAGO by Jacob Riis (1900)

Jacob Riis, a Danish immigrant who experienced poverty in his younger years worked at a series of jobs before becoming a police reporter and photographer in the 1880s when he encountered the distressed “other half” of humanity in overcrowded slum tenements. Through powerful visuals and the words of a crusading journalist his brand of reform Christianity quickly defined a productive career–total “war” against the slums. Riis’s role as a prolific writer and photographer of slum peoples and conditions gained him an iconic status as an innovative and influential Progressive era reformer.

No journalist and photographer before Riis had effectively framed for vicarious viewers what urban poverty looked like–from the safe distance of the camera lens. His signature photo drama simultaneously elicited the expression of shock on the faces of the impoverished and the awe of middle-class viewers for the squalor, chaos, hopelessness, bleakness, and emotional depravity of slum existence.

Exploding magnesium powder flashing in a frying pan which resonated like the retort of a firing gun, Riis illuminated previously inaccessible dark, cramped, and closed spaces in tenement living. His primitive camera techniques exaggerated the light on blemishes and dirt in confined passageways, alleys, and accentuated the stunned shining stares in the flat eyes of his subjects.

A Jane Addams correspondent, and warm friend of the Hull-House Settlement, Riis in 1900 accepted an assignment from the Chicago Daily Tribune to work on a special six part series, “The Story of the Slum” which included a tour of West Side streets in Chicago. “Maladministration, or none at all, was the sum total of the impression made by the brief trip through your tenement streets,” he concluded, “They are a stain–a threat. You cannot raise civic ideals out of such soil. It doesn’t grow there.”

New York had its “Poverty Gap” and Chicago its “Poverty Flat,” a big double tenement on Ewing Street. “The tenement was well named: dirty, ill-kept, evidences of neglect, slovenliness, unthrift in every angle, every window pane. It was fit for nothing but to tear down.”

In his Autobiography, Riis delivered the ultimate judgement of condemnation of Chicago’s West Side slum: “For never was parody upon Christian charity more corrupting to human mind and soul than the frightful abomination of the police lodging-house, sole provision made by the municipality for its homeless wanderers. Within a year I have seen the process in full operation in Chicago, have heard a sergeant in the Harrison Street Station there tell me, when my indignation found vent in angry words, that they cared less for those men and women than for the cur dogs in the street.” bjb

- Part 1-Chicago Daily Tribune, March 11, 1900

- Part 2-Chicago Daily Tribune, March 18, 1900

- Part 3-Chicago Daily Tribune, March 25, 1900

- Part 4-Chicago Daily Tribune, April 1, 1900

- Part 5-Chicago Daily Tribune, April 8, 1900

- Part 6-Chicago Daily Tribune, April 15, 1900

SLUM LIFE: POPULAR CARTOONS (1889-1922)

The popularity of cartooning from the late nineteenth century spoke to the immediacy and importance of a topic of interest in the daily lives of respondents who preferred to view a picture before the act of reading and perusing a text. Political comedy functions by caricature, lampoon, satire–pricking the hot air of narcissist self-exaggeration and flatulent official pronouncements from the ambiguities and complexities within a person’s experience. Political comedy belongs in the vulgar American slang genre of “bullshit” first appearing in the later nineteenth century, and prospering since.

In the cartoon above the “slum wag” mocked the naive visiting “slummer” who presumed that human misery was a market commodity attracting tourists who were good for neighborhood business. bjb