CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

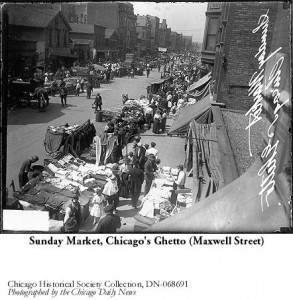

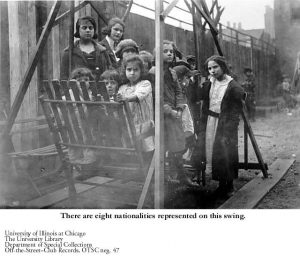

GHETTO LIVING WEST SIDE

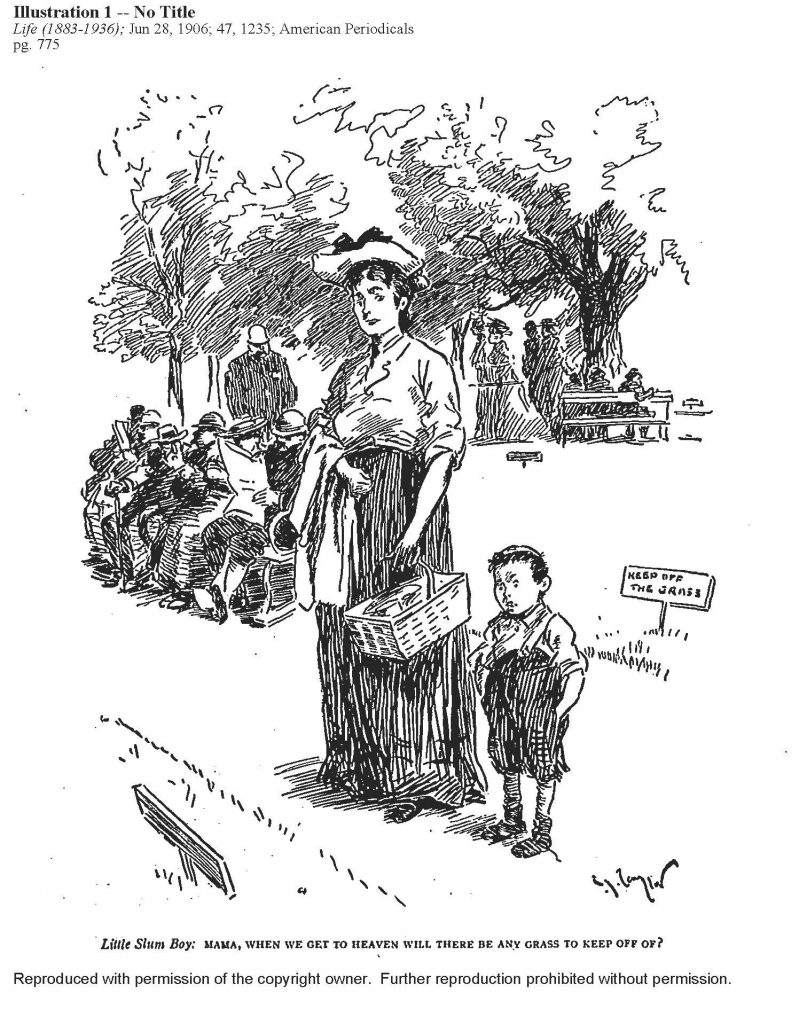

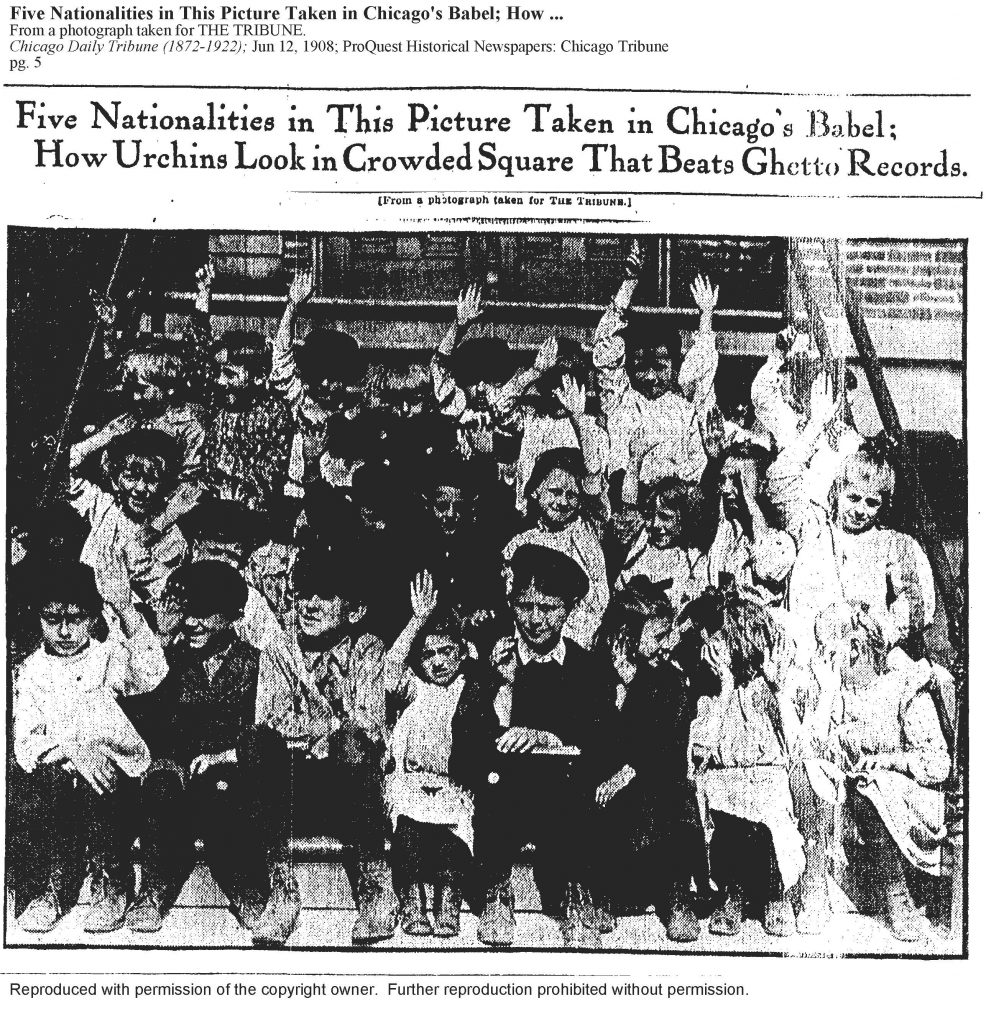

“Slum”–a largely middle-class slang reference to squalid streets and alleys in a densely crowded city district populated by low class, poor, and lethargic, apathetic immigrant peoples–appeared in the U.S. in the 1870s. In 1892 an assimilated Anglo-Jewish playwrite, Israel Zangwill, incorporated the densely populated and segregated “ghetto”–a swarming place for poor and ignorant Jews–as synonymous with “slum.”

In 1893 signing on to work for the U.S. Labor Department’s investigation., the Hull-House social workers selected the West Side of Chicago as representative of an urban slum. They characterized it by maladapted foreign populations living within an isolated netherworld of human waste, moral dissolution, and the machinations of “slum politicians”

By the 1940s, the concept of the dysfunctional and segregated “slum” expanded to embrace native-born Blacks, Latinos, and non-white minorities. Their daily lives were depicted as riddled by hard drugs, vicious street crime, soaring rates of adolescent pregnancy, and welfare dependency. The negative associations of impoverished and lawless “slum” and “ghetto” were now mirror images.

Historically speaking, semantic usage clarifies that “ghetto” was an older and exclusive concept from 15th century Italy. It does not bear all the modern pejorative weight of “slum” from the 19th century. “Ghetto” meant Jews who exclusively lived or were compelled to stay within the walls by law of a special quarter or place. Frankfort, Budapest, Rome, Venice, Vilna, were among the largest, best-known historical European Ghettos.

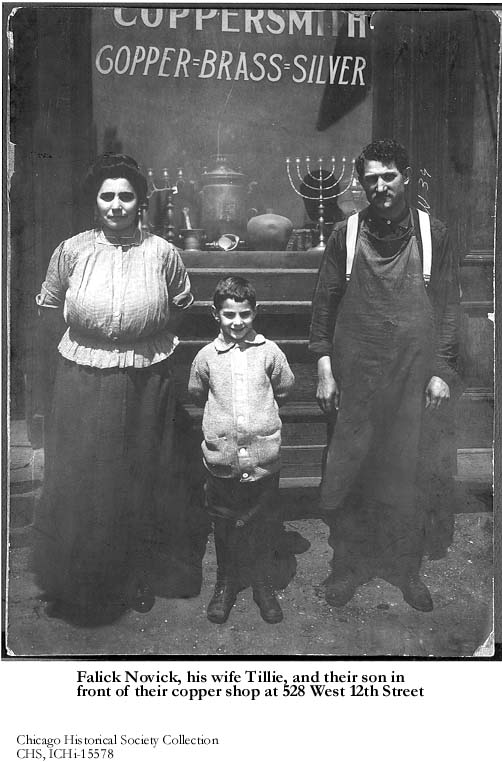

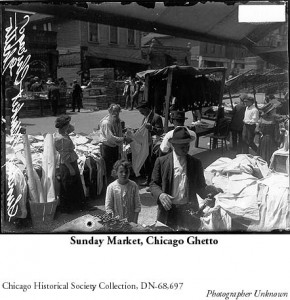

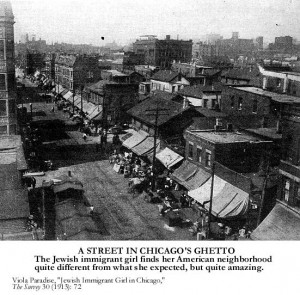

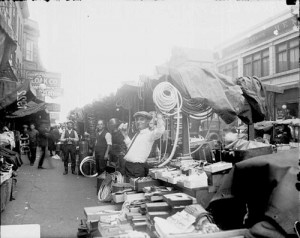

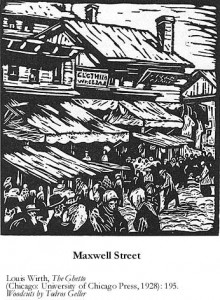

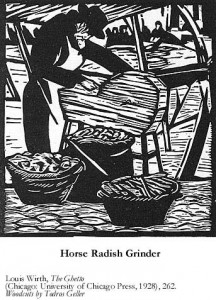

On the West Side of Chicago, observers and commentators alike noted, a Jewish “ghetto” existed within a slum. However, only to the superficial view of outsiders did it resemble merely a replica of another impoverished and dissolute neighborhood. Uninformed journalists and “slumming” voyeurs and tourists, focusing primarily on the shabby appearance of the deteriorating environment, were deceived by the intensity of a concealed inner-city business district. Working immigrants were usually invisible from public view inside the shops, workplaces, and tenement apartments.

The economic, religious, and cultural energy, and indeed exploitation of family labor, within the walls (actual or invisible) of the Chicago ghetto were more instructive than from outside the walls. Charles Bernheimer observed in The Russian Jew in the United States (1905):

“The West district contains … Russian [Polish] Jews, who pay high rents for the privilege of living in insanitary houses. Fortunately, conditions are not so bad there as they seem on first sight. Walking through the streets of the neighborhood one is shocked by the dirt and disorder. But it is the aesthetic not the moral sense that is outraged. The district is not really a slum. Evidence of education, morality, and intelligence are found in abundance. With the exception of incorrigible boys and petty gamblers, there is no vicious element. Temperance rules supreme. Soda water is sold at the grocery stores at two cents a bottle and at the stands for one cent a glass. This in summer and weak tea in winter are the national drinks of the Russian Jewish population.”

A decade earlier in 1895, Charles Zeublin’s view was darker. Born in Indiana and educated at American higher education institutions, he became a professor of Sociology at Northwestern University, later at the University of Chicago. He had a close relationships to the Hull-House social workers. Zeublin argued that the greatest need of the Chicago ghetto pointing to its success would be “annihilation.” bjb