CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

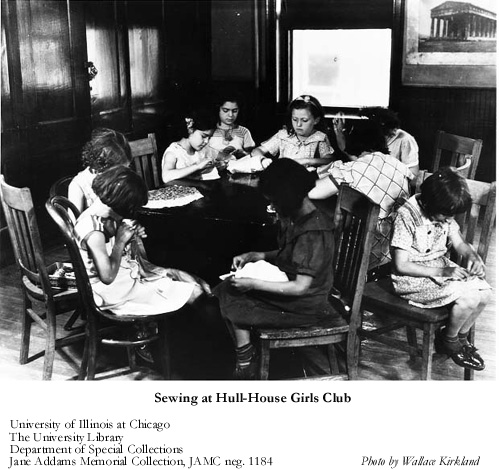

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

WORKING GIRLS, MOTHERS, WOMEN

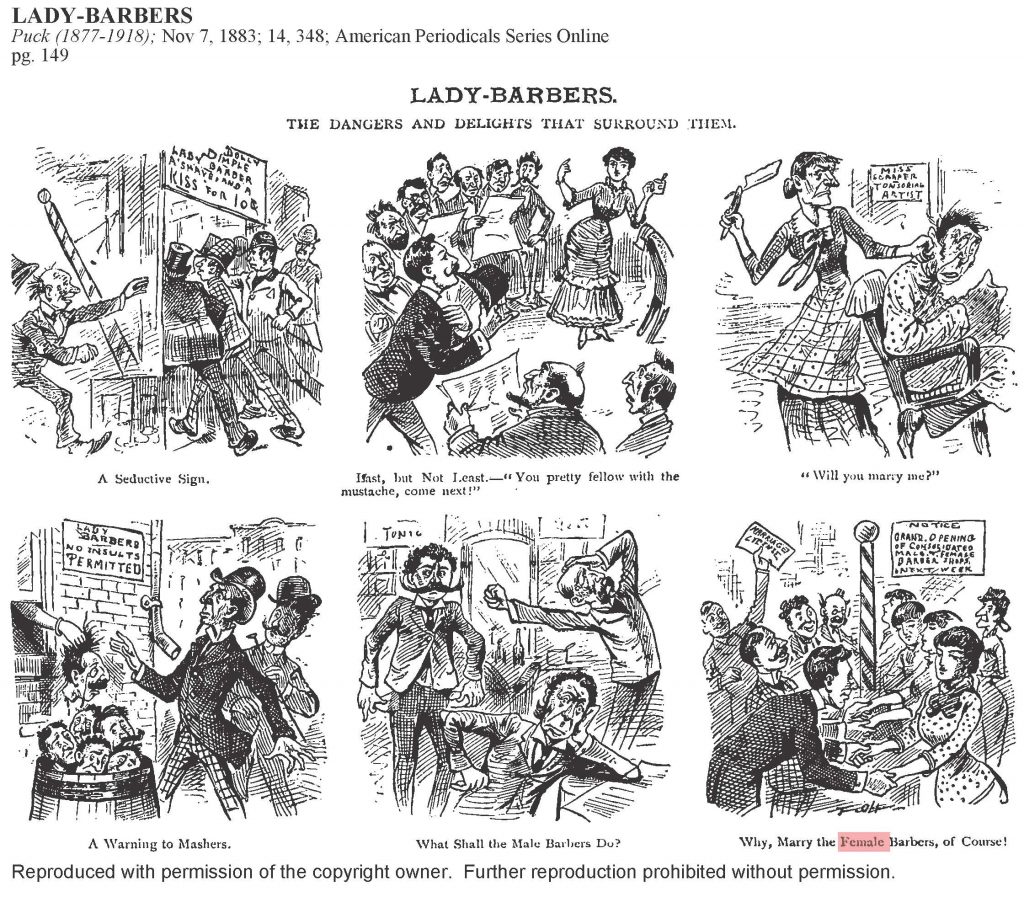

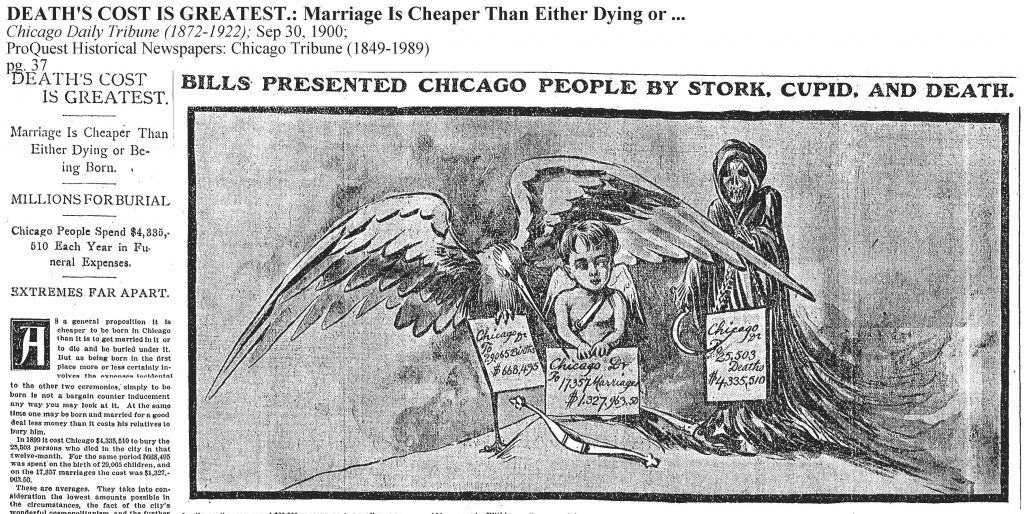

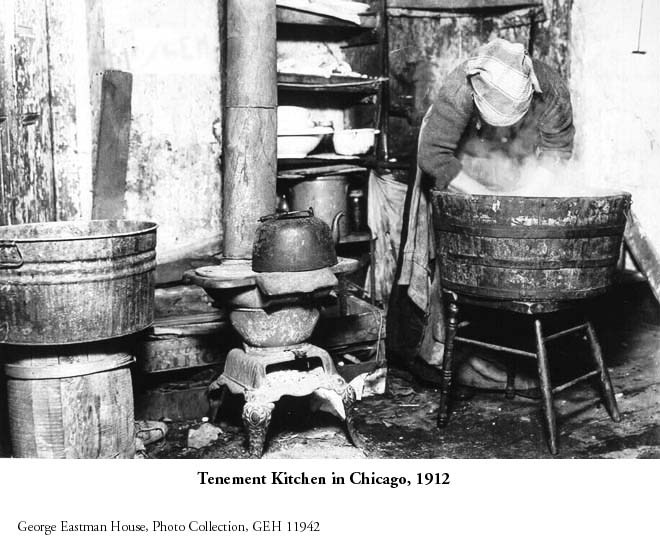

In contrast to middle-class and club women, immigrant and emigrant girls and women who came to Chicago worked in the economy, often long hours in factories, shops, stores, and at homework. Cheaper to employ than men, they commonly worked at unskilled jobs, toiled anonymously, and lacked many options. In family businesses they became a de-facto resource of unpaid labor. Unions also shunned women.

As Theodore Dreiser explained when Sister Carrie left rural Wisconsin in 1904 to stay with her sister on Van Buren St., the girls were coming to Chicago by the thousands for opportunities to support themselves. Chicago was a promising land where the girls presumed they would be immeasurably better off than remaining in the bleak economies and stultifying small towns where they came from.

From the impoverished and politically oppressed small towns of Eastern Europe, as both Elias Tobenkin (1909) and Viola Paradise (1913) related, families sent their daughters to work in Chicago. With luck they would land a husband. “Greeny” girls–as the unskilled were called–experienced abuses, exploitation, and discriminatory exclusions in Chicago labor markets. Still they came in numbers, in significant cases demonstrating resourcefulness at boosting their standard of living and defying traditional family norms for arranged marriages and subordinate obedience.

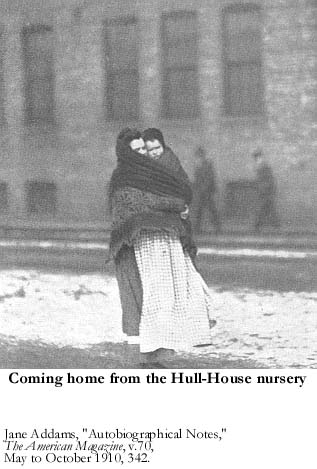

Among reformers, such as Jane Addams and Louise DeKoven Bowen, working girls were a subject of intense interest charged with pervasive anxiety. Especially for “bad” girls, reformers blamed the failure of the working immigrant mother and boarding houses single girls where the supervising presence and surveillance of a housekeeper mother were absent. In immigrant families older siblings were involuntarily recruited as the day-time caretakers for younger brothers and sisters,

Boys were a problem, but as Ben Lindsay of the Juvenile Court said, the consequences for the “troubled girl” were worse by twenty times. Jane Addams concurred in vivid terms having observed first-hand “adolescent” girls in the city.

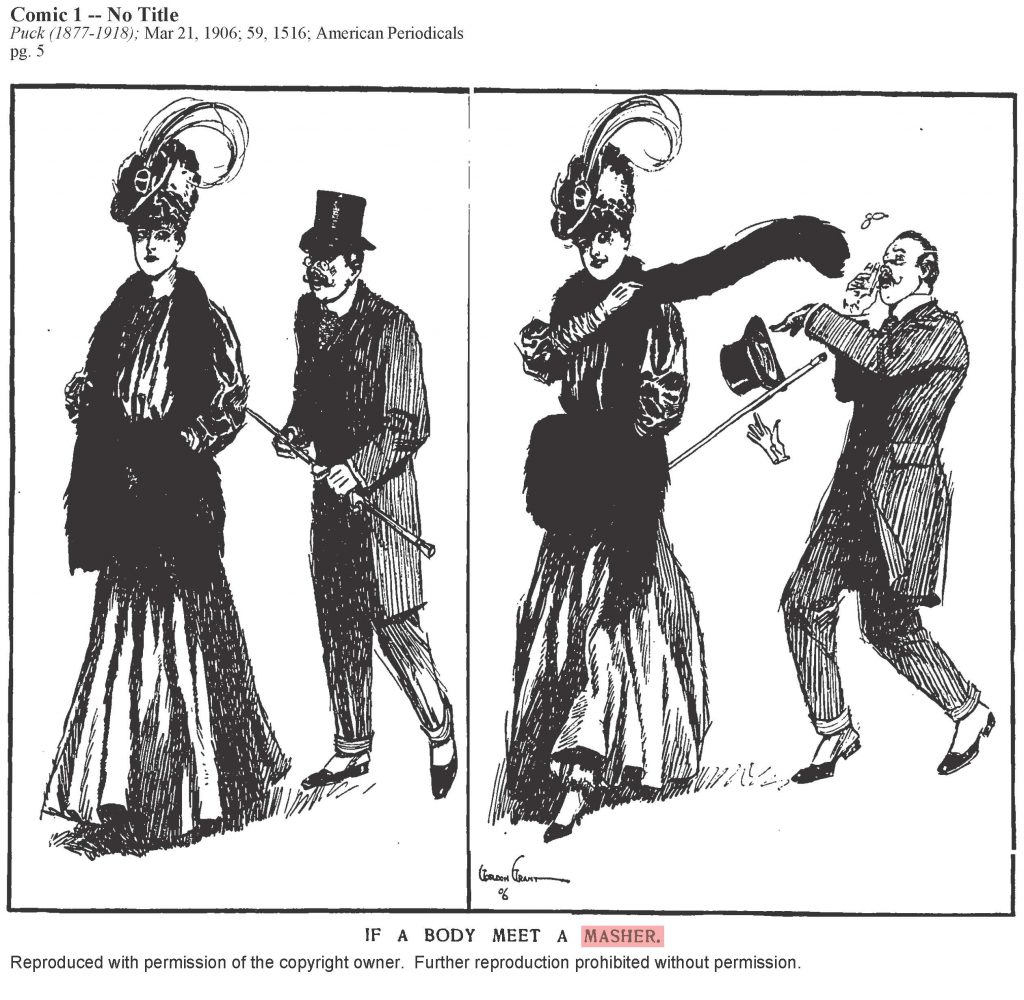

In The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets (1909) Addams dramatized at length the perils facing thousands of girls going to and from “uninteresting jobs” every day in low-wage trades. The girls compensated by developing “overstimulated senses” for the adventure of fashionable hats, dress-wear, and “ruby lips.” In a neighborhood with cheap theaters and dance halls Addams drew attention to the cases fatally “gone wrong” by “flings” with a “recreant lover.”

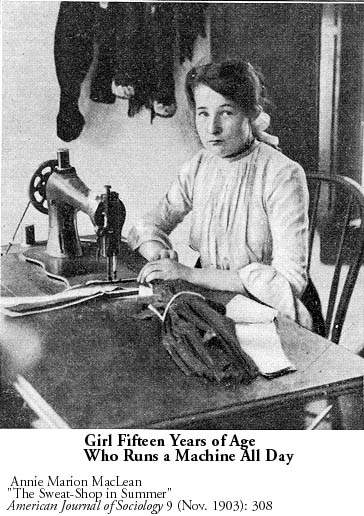

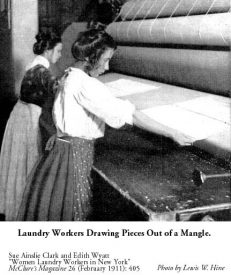

With the advent of the portable street detective camera pioneered by Lewis W. Hine’s photographic investigation of industries, trades, sweatshops and homes, unprecedented images of the diversity of labors performed by girls and women visibly emerged from the shadow lands of hidden female toil. bjb

INTRODUCTION

PHOTO GALLERY

WORKING GIRLS IN CHICAGO (1909-1913)

- The Immigrant Girl In Chicago by Elias Tobenkin (1909)

- Bricks Without Straw: The Story of an Italian Girl Among the Striking Garment Workers in Chicago (1910)

- The Kindergarten of the Factory Girl: Initiating the Working Woman Into the Principles and Benefits of Organization by Sarah Comstock (1910)

- The American Jewish Girl in Chicago by Viola Paradise (1913)

- Working Conditions in Chicago in the Early 20th Century, Testimony Before the Illinois Senatorial Vice Commission (1913)

- Working Girls in the Stockyard District by Louise Montgomery (1913)

- Sally Levin, Hull-House Oral Interview by Mary Ann Johnson

- See “Cheap” Economy: Strike, Walkout, Wage and Labor Action

- See Ghetto Living West Side: Elias Tobenkin, Reporter, Journalist, Editorial Writer

SHOP GIRLS IN CHICAGO (1891-1912)

- From Dark to Bright, What Working Girls Suffer (1891)

- Life of Shop Girls (1899)

- Shortage in Shop Girls (1901)

- Troubles of a Working Girl (1905)

- Which Are Prettier? The Society Women The Working Girls (1906)

- No Working Girl Can Live Comfortably Away From Home on Less Than …. (1907)

- Ways For The Working Girl To Live, Don’t Live in Boarding Houses (1907)

- Want Daughters in Unions (1907)

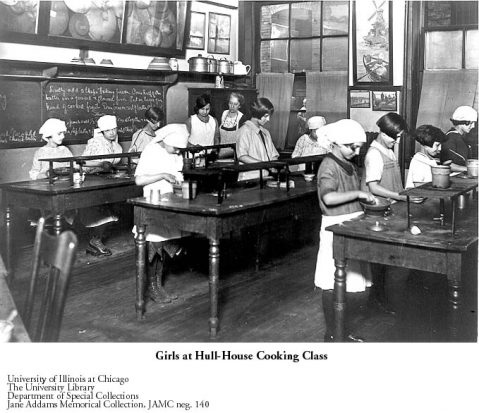

- Training Girls To Be Domestics; When They Learn They Strike (1908)

- Why The Immigrant Girls Refuse To Become Domestics (1908)

- Little Women, Wonders of The Slums, Take Up Life’s Burdens Early (1908)

- Oldest Daughter Now in Revolt, Factory the Stepping Stone (1909)

- Beautiful Shop Girls of Chicago (1908)

- All Work And No Play Makes Jane a Dull Stenographer (1910)

- New Type of Womanhood Forming; Working Girl Athene of Future (1911)

- Is This Pretty Bon-Bon Dipper Chicago’s Most Beautiful Working Girl? (1912)

WORKING WOMEN AND MOTHERS IN CHICAGO (1896-1909)

- Women Crowd The Gyms (1896)

- Babies Mothered by Proxy (1901)

- Chicago Army of 160,000 Working Women; Procession Begins at Dawn (1903)

- Working Women’s Unions Praised (1906)

- Deserted Wives In Ghetto; Find Work in Junk Shops (1907)

- Cupid Guides Ghetto Nurses (1907)

- Immigrant Children Slaves To Filial Love (1907)

- Odd Trades In The Ghetto; Women Who Mend Bags (1907)

- Women Of Toil Own Industries (1907)

- Children Of Poor Old Age Pensions Of Their Parents (1908)

- Ten Hour Work Day For Women; How It’s Viewed From All Sides (1909)

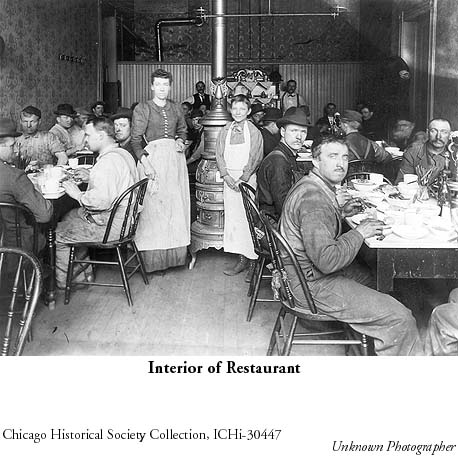

- Work In Restaurants Preferred (1909)

JANE ADDAMS ON WORKING WOMEN, WHY GIRLS GO WRONG (1904-1914)

Among reformers, such as Jane Addams and Louise DeKoven Bowen, working girls were a subject of intense interest charged with pervasive anxiety. Especially for “bad” girls, reformers blamed the failure of the working immigrant mother and boarding houses single girls where the supervising presence and surveillance of a housekeeper mother were absent. In immigrant families older siblings were involuntarily recruited as the day-time caretakers for younger brothers and sisters. The Hull-House remedy: “Mother Belongs at Home; Otherwise the Morals of the Family will Suffer.”

“Never before in civilization have such numbers of young girls been suddenly released from the protection of the home and permitted to walk unattended upon city streets and to work under alien roofs; for the first time they are being prized more for their labor power than for their innocence, their tender beauty, their ephemeral gaiety.” bjb

- Mother Belongs at Home; Otherwise the Morals of the Family will Suffer by Jane Addams (1904)

- Why Girls Go Wrong by Jane Addams (1907)

- The Progressive Party’s Pledge To American Working Women by Jane Addams (1912)

- The Girl Problem by Jane Addams (1914)

WORKING GIRLS AND WORKING WOMEN, PHOTO BY HINE (1908-1913)

- The Woman’s Invasion I (1908)

- The Woman’s Invasion II (1908)

- The Immigrant Girl In Chicago (1909)

- The Irregularity of Employment of Women Factory Workers (1909)

- Working-Girls’ Budgets: Self-Supporting Girls (1910)

- Working-Girls’ Budgets: Shirtwaist-Makers and Their Strike (1911)

- Working-Girls’ Budgets: Unskilled and Seasonal Factory Workers (1911)

- Women Laundry Workers in New York (1911)

- Artificial Flower Makers (1913)

- Women In The Bookbinding Trade (1913)

WOMEN IN THE TRADES, PHOTO BY HINE

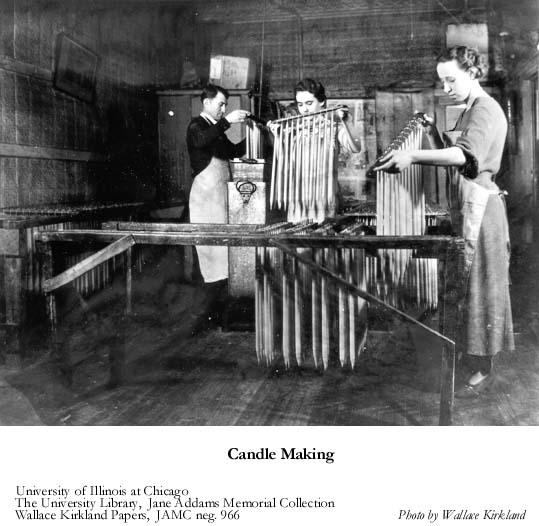

During Lewis Hine’s formative years growing up in Oshkosh, employers, management, and absentee owners relegated work and working people into a shadowy background. Employment by Kellogg and the Pittsburgh Survey now focused Hine’s attention. The camera reaching a large audience, he believed, would bring to light a more realistic and human picture of the conditions under which women in particular but also men worked in the new industrial order. It was a picture largely inaccessible in presentations sympathetic to ownership interests.

In the urban industrial context, both women home workers and factory labor were replaceable parts in a production machine. Inconspicuous and hidden from view, this new labor force often toiled as piece workers for meager wages. Hine pictured actual women at real work with no glory or joy: at homework with children around a table, employed at high-speed machinery, compelled to keep up with the pace on shop floors. They operated dangerous equipment, kept an assembly line moving, sorted fabricated parts, handled table tools, warehoused finished products. Men invariably appeared in superior supervisory or skilled roles. By means of Hine’s camera, an original body of evidence came to light including the employment of a large population of working class female lives. Real women implicitly with names, personal histories, families, active lives in urban neighborhoods were now embodied in a new graphic language. bjb

- Title Page: Women & The Trades

- Glass Decorators-Frontispiece

- Body Ironer at Work-p.183

- Bottling Olives-p.41

- Bottling Pickles & Onions.-p.33

- Cellar Stripping Room-Stogy Factory-p.363

- Coil Winding Room-Westinghouse-p.219

- Dangerous Staying Machine-p.261

- Feeder at Cylinder Mangle-p.169

- Filing & Capping Mustard Jars-p.37

- Folders-Job Printing Office-p.279

- Garment Workroom-p.103

- Glass Decorators-p.245

- Glassware-Wash-Clean-Packing-p.239

- Head of the Checkroom-p.191

- Laundry Ironing Room-p.187

- Lunch Room-Stogy Factory-p.311

- Mica Pasting Department-Westinghouse-p.215

- Mold Stogy Rolling-p.85

- Operators at a Mangle-p.173

- Pasting Cigar Boxes-p.257

- Sorters in Sheet-Tinplate Mill-p.227

- Starching by Hand-p.177

- Stripping Tobacco-p.79

- Sweatshop Proprietor-Employees-p.95

- Telephone Exchange-p.287

- Tobacco Strippers-p.97

- Tobacco Stripping in Sweatshop-p.87

- Types of Laundry Workers-p.201

- Women Core Makers-p.211

- Working at Suction Table-p.91

- Working Girls Club-p.325