CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

HOBOHEMIA ON WEST MADISON STREET

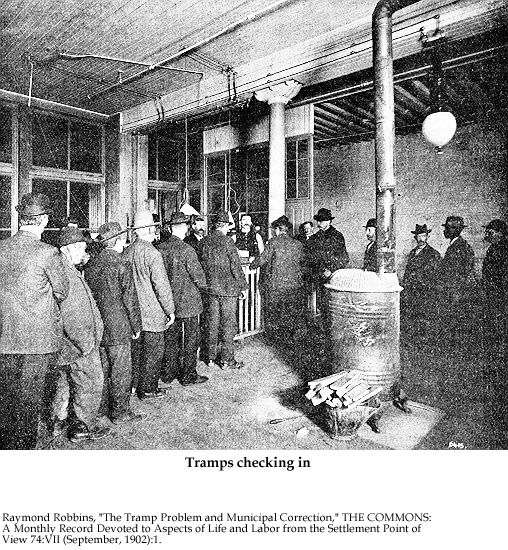

“Hobohemia” on West Madison Street in tramp jargon was “the main stem” for “Knights of the Road.” With the rise of Chicago as a national railroad center in the later nineteenth century, the inner city became the central location and clearing house for seasonal traveling workers riding the rails to seek employment in every section of the nation. Chicago being the greatest railroad center had the largest Hobohemia in all U.S. cities.

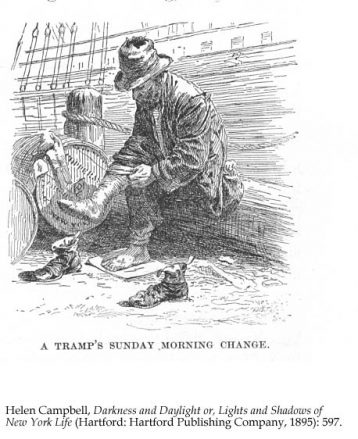

“Hobo,” a word of western U.S. origin, was much misunderstood, conflated by settled respectable folk with threatening conduct from the vagrant “tramp” who worked only when forced to, the homeless “bum” who did not work at all, and the “yegg” a thief and robber.

Harper New Monthly Magazine in 1895 described the hobo as a “wandering unemployed person, a stealer of rides on freight trains, a diner at the back door, eternally seeking honest work” to earn a living. “The true hobo,” Nels Anderson wrote in 1923, “was the in-between worker, willing to go anywhere to take a job, and equally willing to move on later.” His occupation “made mobility a virtue.” Each hobo responded to a different series of preceding events from their former lives, and “each arrived in Hobohemia by a different route.”

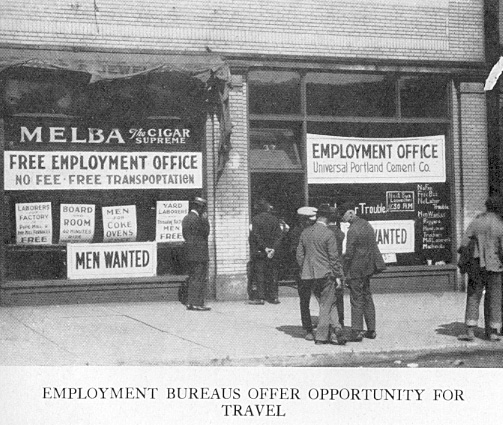

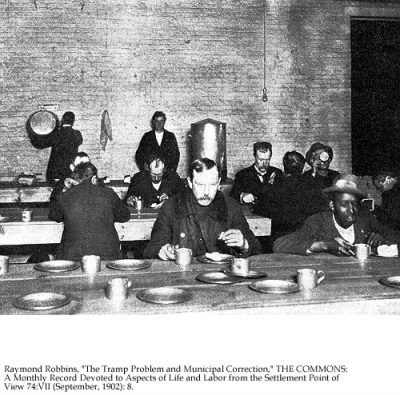

Hobohemia in Chicago provided the itinerant workers with lodging, medical facilities, cheap restaurants, employment bureaus, and commonly met their needs, especially for fraternization with women and medical treatments for disease. Hobos were not “homeless” as misrepresented by an editor for University of Chicago publications who presumed, as did many, that all hobos were ne’er-do-well vagrant tramps and imposed the subtitle on Nels Anderson published work (1923).

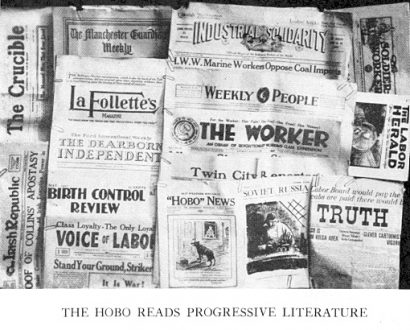

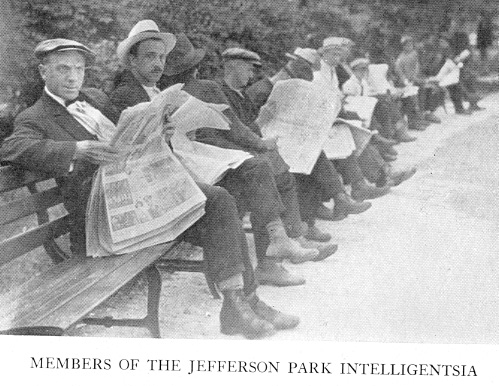

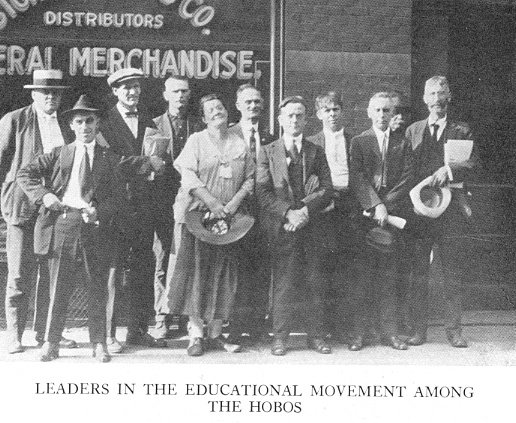

Hobohemia, one contemporary observed. “constitutes a city within a city–a distinct culture with its own institutions–economic, recreational, religious, and educational.” Hobos had high literacy rates and were addicted to newspaper sports pages as well as left-wing political tracts and traditions of protest song. Chicago’s Hobohemia actively supported education including a Hobo University with a regular faculty. The “red card” carrying Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) with headquarters in Chicago’s Hobohemia was identified as a hobo organization. bjb

INTRODUCTION

HOBO AND TRAMP: PHOTO GALLERY

NELS ANDERSON, THE HOBO (1923)

Nels Anderson was born in Chicago in 1891. His father was an immigrant and qualified bricklayer and his mother from Swedish immigrant parentage. The family was Mormon and gave birth to twelve children. With the father’s trade in demand, the family followed the construction jobs traveling around the country. As Nels described it, he belonged to a migratory “hobo family” beating its way across the country always in need of making a self-sufficient living in a fluid economy

In 1901 the family returned to Chicago and settled in the vicinity of the “main stem” at Halsted and West Madison Streets. “We were slum dwellers, which I learned years later.” Money was tight, the family skilled at buying cheaply on the Westside. Hobohemia was home turf, a place of vivid boyhood memories. Nels plied the street trades befriending clerks in flophouses, friendly policemen, and prostitutes who paid him to run errands. (See his account in “The Mission Mill”).

After Chicago, Nels moved around as a transient laborer, served in the Army in WWI, did some college work at Brigham Young University in Utah. In 1921 at age 32 he returned to enter the M.A. program in Sociology at the University of Chicago, and supported himself as a full-time male nurse in an asylum.

At the University, Nels background was unique. A social class difference separated him as an outsider from the professors and students at the elite university. His chosen research topic was the Hobo, a scandalous topic among his peers. They assumed he must know other disreputable characters and would have a pernicious influence in the classroom, disqualifying him for recommendation to a teaching position.

Revealed by archival documents, Nel’s mentor Robert Park spent no more than fifteen minutes talking with him about the dissertation and asked no questions. An additional irritant with Park must have been that Nels professed no interest in becoming a “toady” of the current academic practices. He listened rather than took notes in class, and his “unscientific” methodology was to talk with residents in his comfort zone of Hobohemia, a technique now called “participant-observation.”

When Park declared his interest in publishing the M.A. thesis with the University Press, with no substantive changes, Nels laughed thinking it was not a publishable piece. Why Park recommended publication, beyond the reality that as general editor of the sociology series he needed a first publication, remains unclear. bjb

- 1-Hobohemia Defined

- 3-Homeless Man at Home

- 4-Getting By in Hobohemia

- 6-Types: Hobo and Tramp

- 7-Types: Homeguard and Bum

- 8-Types: Work

NELS ANDERSON: ESSAYS (1923-1928)

HOBO COLLEGE CHICAGO (1916-1922)

- Hobo College Loses Students (1916)

- Hobo College About to Open (1916)

- ‘Bos and U.oF C. Men Indulge in Oratory Orgy (1917)

- Bolsheviki Idea in Hobo College Inspired Rival (1917)

- Pastor Obtains Chat Chamber For Hobo Band (1917)

- Hobos to Join U.S. Surgeons Fighting Germs (1917)

- Hobo at School Learns How He Looks to World (1921)

- Hobo Literati Will ‘Sub’ for U. OF C. ‘Profs’ (1922)

- Nels Anderson, The Hobo College pp. 172-178

- Nels Anderson, The Hobo College pp. 237, 227

HOBOS AT HULL-HOUSE (1907-1914)

- Home of Own For Hobos, Chicagoan Plans Haven (1907)

- “Queen of Hobos” Knocks ‘John G. Rockefeller’ (1913)

- Hobo’s Song Brings Tears, “Old Kentucky Home” (1913)

- Want Riches? Easy! Biff!–Work (1913)

- I.W.W. Leaders Upset Plans King of The “Hobos” (1914)

HOBOES THAT PASS IN THE NIGHT (1907)

WHAT RACE MAKES THE BEST HOBO (1892-1911)

- Tide Over the Winter, Tramps Breaking West-Side Plate Glass Windows To Be Sent to Jail (1892)

- Tramps Rob West Side Churches, They Steal Plate from the Altars (1896)

- Overcoats Warm the Hobos’ Backs, One in Three will Soon Sport Spring Style (1903)

- On and Off The Bread Wagon, Amateur Hobo Quits the Road (1905)

- Good Samaritans Few in Chicago (1907)

- Hard for Hobo To Get Work, Reformer has Little Chance (1907)

- Hobos Ask Work, Bureau is Open (1907)

- What Race Makes Best Hobo: Good Tramp Never Works (1908)

- Calls Everyman Potential Hobo (1911)

- Four Cents a Day Enough To Live On (1911)

TRAMPING WITH THE TRAMPS by PROFESSIONAL VAGRANTS (1893-1901)

- The City Tramp by Josiah Flynt (1893)

- The Tramp at Home by Josiah Flynt (1893)

- Tramps Glossary by Josiah Flynt (1893)

- Tramps Jargon by Josiah Flynt (1893)

- ‘Chi’ an Honest City by Josiah Flynt (1901)

MAKING AN EXEMPLARY TRAMP (1902-1925)

- The Tramp Problem and Municipal Correction by Raymond Robins (1902)

- The Making of a Tramp by Mariner J. Kent (1903)

- Vagabondage, The Tramp Life by William Healy (1918)

- The Making of a Hobo by Robert E. Park (1925)

TRAMPING IN CHICAGO (1890-1909)

- A Coal Hustlers’ Trust, a Queer Organization of Tramps in Chicago (1890)

- Bunks in The Slums…A West-Side Lodging House (1896)

- On “Hoboes”, Tramp Returns from his Summer Outing (1897)

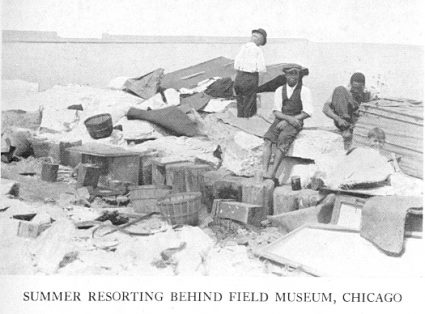

- Neglect Drive by Lake Shore, Once Beautiful Boulevard and Park, Unmolested by Police, Turned into Ugly Dumping Ground (1900)

- Tramps Beginning Summer Travel, Chicago the Clearing House in the Annual Migration (1904)

- “Woman Tramp” a Bother, Loiters in State Street Store but Seldom Buys (1904)

- Woman Tramps in Chicago: Homeless Women (1907)

- What Race Makes Best Hobo? Good Tramp Never Works (1908)

- “Tramp Family” Charity Workers’ Newest Problem (1909)

TRAMPS AND HOBOS (1880-1909): POPULAR CARTOONS

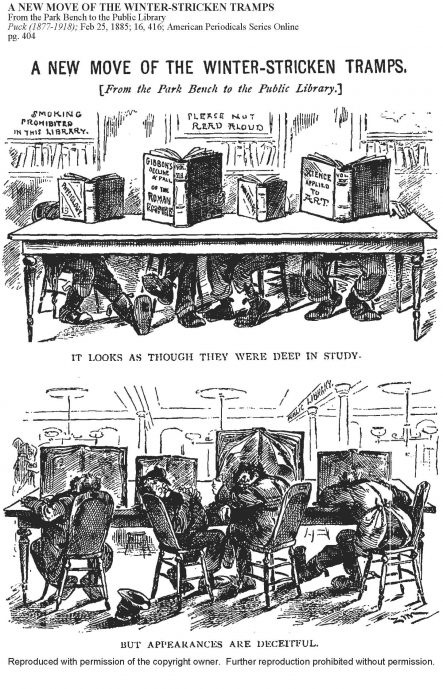

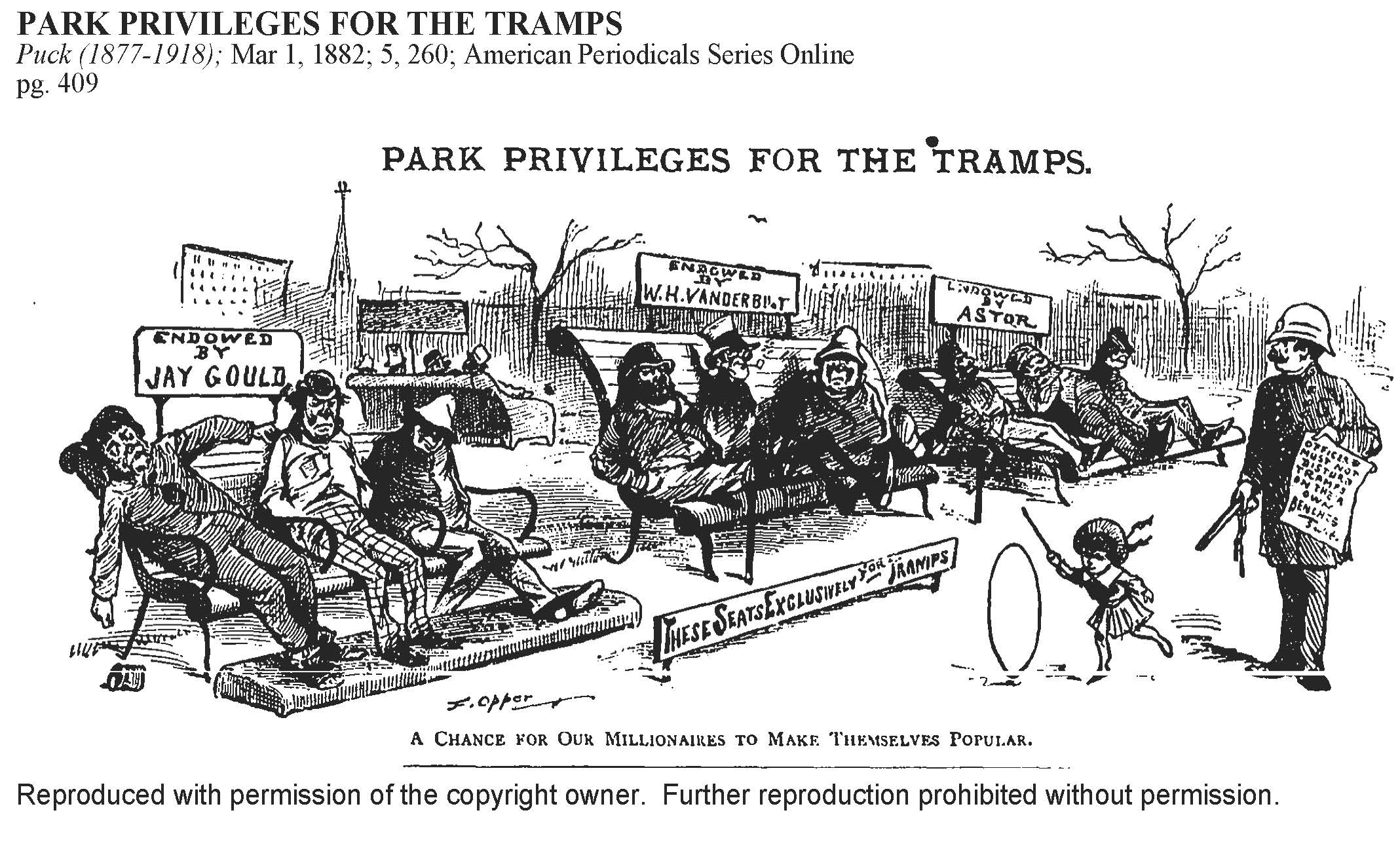

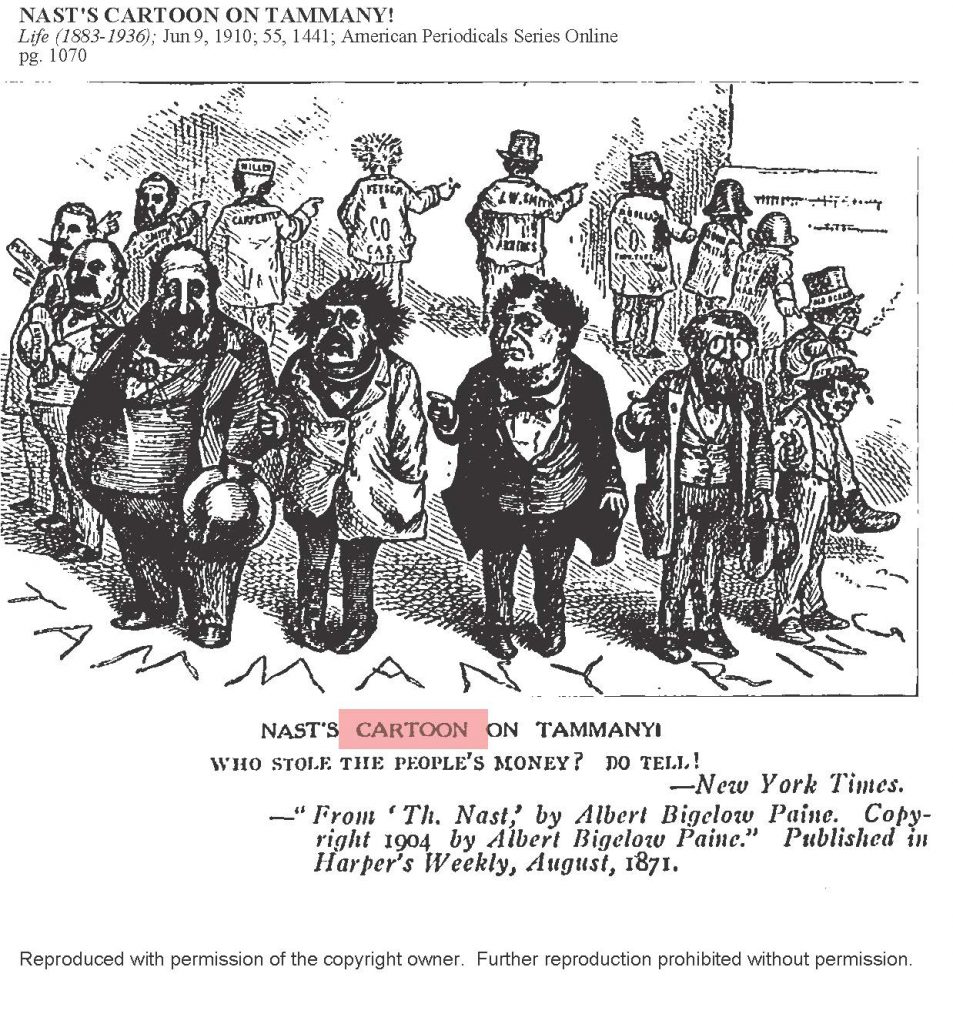

Political comedy functions by caricature, lampoon, satire–pricking the hot air of narcissist self-exaggeration and flatulent official pronouncements from the ambiguities and complexities within a person’s experience. In U.S. magazines and newspapers in the later 19th century, editorial cartooning on politics and culture–local, national, international–became a popular comic art form.

By means of a talented caricaturist and snappy caption, the target of the cartoon received instant recognition in the eyes of a gleeful beholder. A grandiose subject of current interest was diminished to grossly earthy dimensions through laughable humiliation and perverse mockery and ridicule. Raw and unforgiving, cartooning democracy cultivated the “art of ill will.” Nothing and no person was sacred, immune from graphic scorn as a damned “fool”–a vain buffoon, maker of their own gullible foolishness.

“Stop them damned pictures” Boss Tweed of the Tammany Hall political machine is reported to have said after seeing Thomas Nast’s cartoon, “Who Stole the People’s Money.” “I don’t care so much what the papers say about me. My constituents can’t read. But damn it, they can see pictures.”

Three essential characteristics made for the successful magazine and newspaper cartoon presentation.

One, minimal reflection required. The ridiculed target was instantly recognized and the satirical message immediately understood abetted by brief captions. Nothing seemed more absurd to respectable, hard-working Americans than extending privileges to “lazy” hobos and tramps, whatever their sob story.

Two, laughter, mirth, and humiliation, exposing the ludicrousness of vanity and self-righteous propaganda of an adversary were more effective weapons than historical physical confrontation, banishment, dungeons, even jails. Cartooning was effectively combat of a different order.

Three, a direct correlation between the numerical frequency of the appearance of a cartoon subject in print media–city hobos and tramp–and its importance in the immediate lives of the viewing audience. Political comedy fit in the vulgar American slang genre of “bullshit”–“money talks bullshit walks”–first appearing in the later nineteenth century, and prospering since. bjb

- Light and Shade In The Life of a Tramp (1880)

- The Consolidation Movement (1881)

- Park Privileges For The Tramps (1882)

- Our Own Invention, The Patent Park Bench and Tramp Awakener (1883)

- A Leaf From a Tramp’s Diary (1884)

- The Fate Of a Milesian Tramp (1884)

- A New Move the Winter-Stricken Tramps, Park Bench to the Public Library (1885)

- Overreached (1899)

- When The Bloom is on The Hobo (1906)

- Extortion (1909)