CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

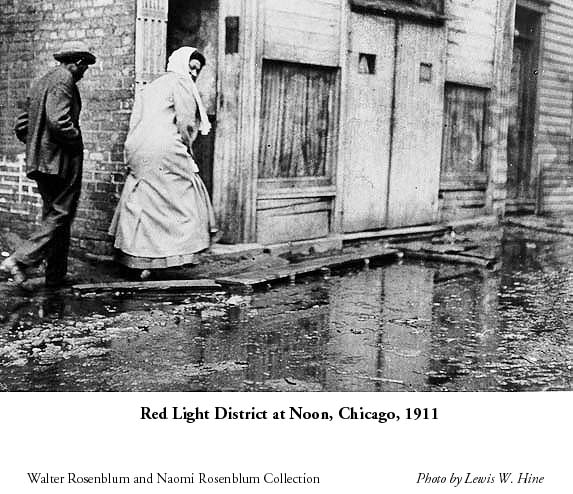

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

At the turn of the twentieth century, the Halsted-Maxwell Street area on the West Side of Chicago was portal to a first generation of immigrants from Eastern and Central Europe and the Mediterranean, destination for domestic migrants from the hinterlands of Midwestern states, and shelter to a celebrated group of middle-class reformers at Hull House. Chicago had quickly risen to become among the premier cities in the world, and the “vicinity” became the nation’s most publicized and visible inner-city neighborhood.

This “slum”–so named by the U.S. Commissioner of Labor in 1893 and the Hull-House residents–-was quintessentially urban with its streets, businesses and residences easily reached by all. Residing in the imagination as well as within spatial boundaries, the West Side was a key location for experiencing modern America in the making.

The area embraced a thicket of tenements, street trades, sweatshops, and factories; shelters and schools. Industrial workers, craft persons, entrepreneurs, clerks, street vendors, storefront hawkers, market jobbers, newsboys and newsgirls, entertainers, professionals, manufacturers, sweatshop operators, hustlers, molls, slumming voyeurs, and tourists – all coursed along the streets that became emblematic of the density of an urban business district immediately beyond the Chicago Loop: Halsted, Maxwell, Jefferson, 12th St. (Roosevelt Rd.), and Blue Island.

The dynamic in the district was the movement of peoples. On her visitations a Protestant Missionary noticed every time she went out, “it was almost like going on a new field …. I was sure to meet with some one who had not lived there before two weeks before I made my visits.” The local directory listed at least three different addresses during five years in the 1890s for the Dena Satt family, a widow caring for five small children.

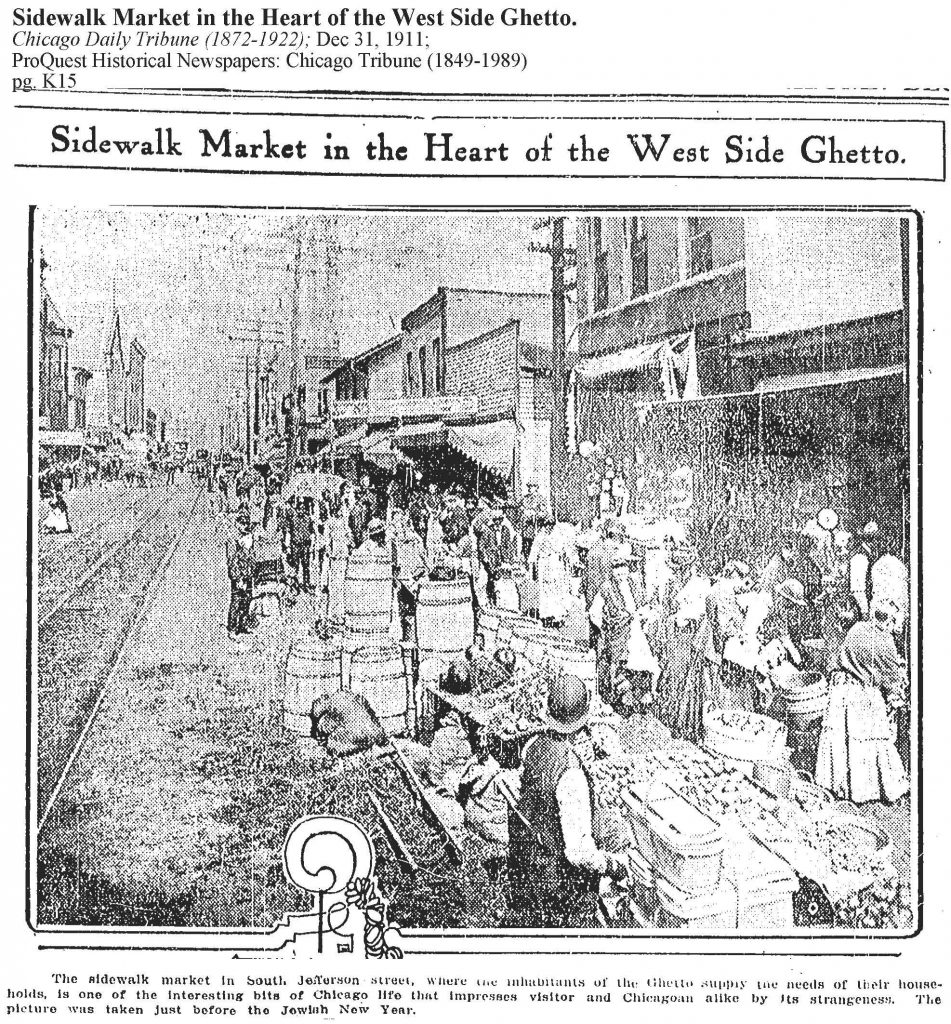

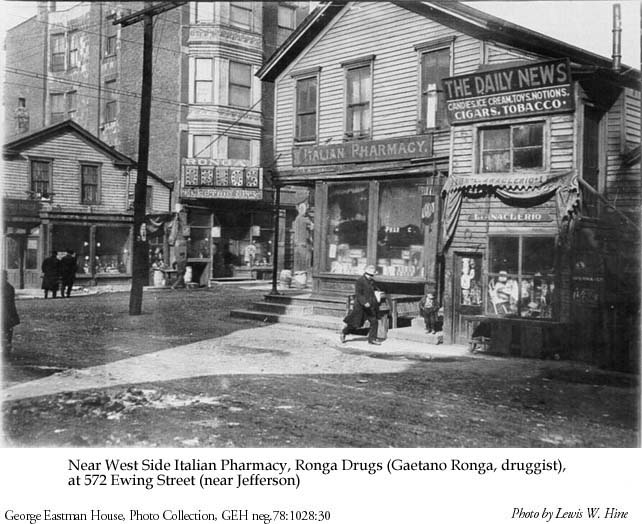

Diversity and incongruity shaped the all-too-human reactions to proximity. “Russian-Hebrews” surged around Maxwell Street and Italians on Taylor Street, Bohemians settled in Pilsen, Irish in Holy Family Parish, African-Americans along Lake Street, hoboes in Hobohemia, middle-class Americans along Ashland Avenue, and Settlement House collegiate workers at Hull-House on Halsted bordering ghetto markets, saloons, Greek coffee houses, meat markets and bakeries.

“The pell-mell of the nationalities is unbelievable,” observed the visiting German sociologist Max Weber in 1904. His primordial experience on Chicago streets reminded him “of a man whose skin is drawn back and whose insides you may see working. For you can see everything.”

Foreign nationals from eighteen countries, alien and race minorities and “white” Anglos, spoke thirty languages on the polyglot West Side streets.

Ethnic businesses in food services, nickelodeon arcades, and popular music represented an “Americanization” of new immigrants. Benny Goodman picked up the beat of jazz and began his musical career on the streets, in the synagogue, and at Hull-House. The White Stockings in the West Side Stadium were paramount players in the professionalization of baseball and the making of what an immigrant Jewish philosopher, Morris Raphael Cohen, called an “urban religion.”

The area residents testified through letters, diaries, journals, newspaper articles, magazines, memoirs, interviews, and fiction. Down these mean streets, an urban sociologist Nels Anderson published the first street-wise classic in urban ethnography, The Hobo (1923). Public Health facilities placed themselves on the cutting edge of new practices in obstetrics, pediatrics, and mapping of incidents of tuberculosis on tenement streets.

Visited by global foreign observers, studied by a first generation of urban sociologists from the University of Chicago, investigated by pioneering medical researchers at the West Side medical center, dramatized in a literary renaissance of urban realism, surveyed by trained social workers at Hull-House–Chicago’s West Side performed as a microcosm for the workings of an urbanizing, foreign immigrant, domestic migrant, industrial, consumer service nation.

Negotiating social and cultural diversity on the West Side was nothing less than hard to do. Living together in close proximity on the cusp of urban life, peoples from different strata and backgrounds, cultures, regions, nationalities, religions, ethnicities, and races who did not particularly like each other could not avoid contacts. They often engaged in provocations and slights. Confrontation, conflict, misunderstanding, and abusive gestures marked the interactions.

“People cursed or raved or snarled but were never heavy or old or asleep,” observed the entrepreneurial Theodore Dreiser, laundryman, bill collector, huckster, newspaperman and author (Sister Carrie 1901) who lived, worked, and prowled along West Side thoroughfares.

Discordant voices made for fresh idiom, innovative ways by which people like Dreiser–a poor German Catholic boy in a family of thirteen children from small-town Indiana–learned to see, speak, think, cope and never lose touch with his graphic and perverse daily realities.

History is local, and the more closely an historian reaches into the daily lives of individuals, families, and neighborhoods the more twists and turns and unpredictable trajectories historical lives take.

Poles and Jews in Chicago, for one, despised each other’s attitudes, religious practices, and very existence, but neither group backed away from a vigorous street trade improving mutually the texture of their daily lives. An observant Louis Wirth contemporaneously noted, “these two groups detest each other thoroughly, but they live side by side on the West Side …. They have a profound feeling of disrespect and contempt for each other, bred by their contiguity and by historical friction in the Pale, but they trade with each other.” Then again, peddling partnerships between Italian and Jewish boys, among whom there could be no love lost, were often forged and appeared to succeed.

In these years what things visually looked like through the lens of a camera began to make a significant difference in human perception and cognition, in what a person saw and how she or he thought about it. With the snap of a shudder, a silent witness now observed how previously invisible peoples lived, worked, played, and prayed.

Ever the human documents.

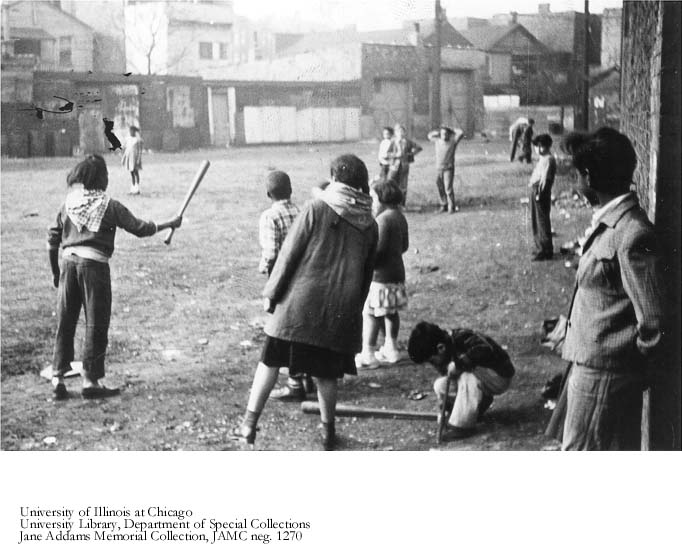

Anonymous photographers brought to light the telling detail of what had previously been beneath notice: rumpled creases on a cheap mass-market men’s suit; dirt smudges on wallpaper in a tenement bedroom adjacent to decorated china porcelain on shelves in a tenement kitchen; anxiety and apprehension reflected in the eyes of recent arrivals walking from the station and searching for a local family address; the ceaseless bargaining, haggling, and protests in city markets; older children tasked with protecting and entertaining younger siblings on sidewalk curbs with mothers and fathers away at work; African-American kids playing baseball in a sandlot.

Central to visual knowledge was the realization that city streets no longer performed as backdrops or stage props for a Victorian melodrama–“character is fate.” On West Side streets, neighbors, acquaintances, and strangers encountered each other, often unexpectedly, as they careered about their transitory business. Location mattered. Urban residents identified and judged each other by their visible careers–their travels in a life-course–not by the clandestine truths of an easily deceptive and often inscrutable “moral character.”

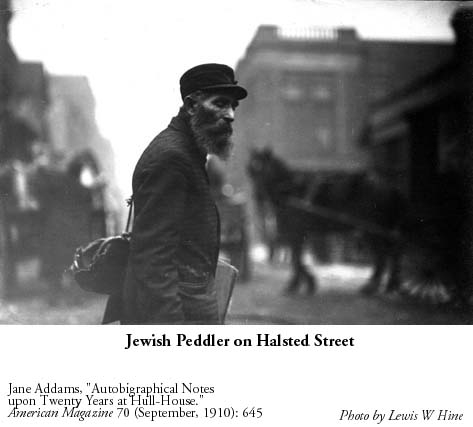

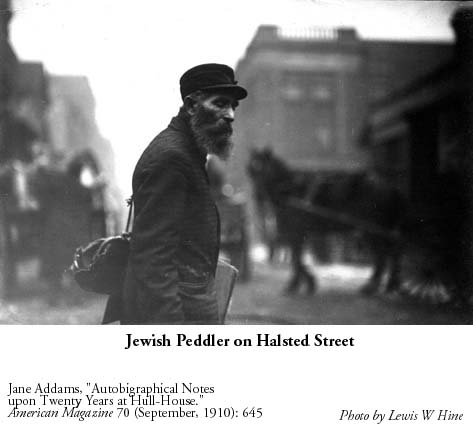

The schoolteacher turned amateur photographer, Lewis Hine, followed by the social worker turned amateur photographer, Wallace Kirkland, found their life vocation by early exposure to the West Side vicinity. The stealth technology of the portable “detective” camera now came of age. (Jane Addams “talked of Hine for Hull House early–she saw the document possibility.”) Disclosed were intimate private details–pleasures as well as abuses–that had not formerly been witnessed by viewing eyes, realities genteel folk with their strong bias for the preservation of public propriety and personal privacy felt some discomfort viewing.

Photographing people and places dramatically challenged the popular illustrated Victorian stereotypes of “degenerate” immigrants living within “vicious” slums. Lewis Hine’s sympathetic weary Jewish peddler crossing Halsted Street in 1910 at the end of a long day, his upper body slightly hunched and bent by the weight of his bags as he stoically glanced sideways down the busy and dangerous thoroughfare, discernibly confronted the familiar image of Henry Mayhew’s antisemitic “Jew Old-Clothes Man” in 1861, preying on the London poor with his piercing satanic eyes and vulture beaked nose.

bjb