CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

BASEBALL

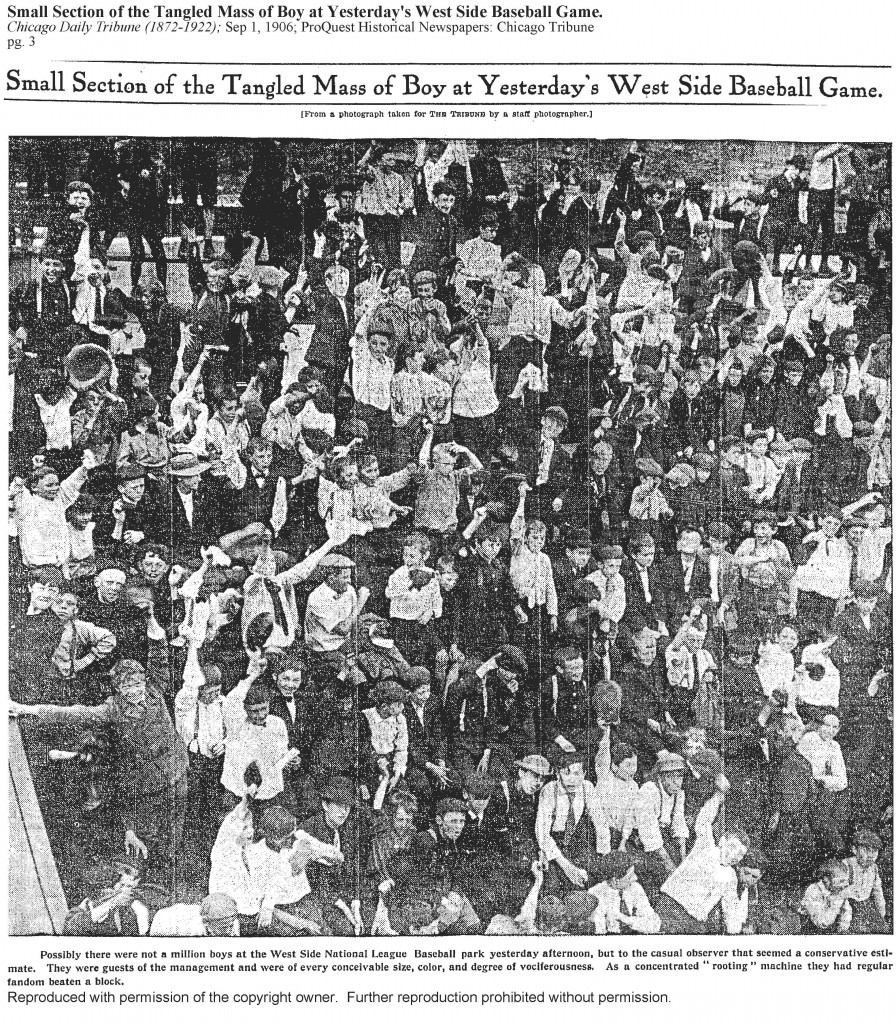

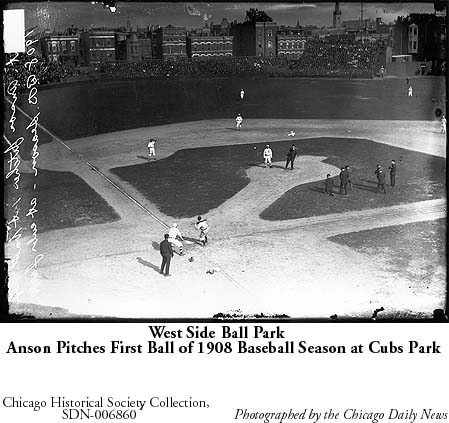

+From the mid-to-later nineteenth century, baseball became an American national pastime. Soldiers played the early game in Civil War military camps. By the turn of the twentieth century the game was popular in urban contexts. Amateur teams played in city parks. Both boys and girls played stick ball in alleys, streets, and sandlots. Professional teams played in a new and accessible stadium on the West Side.

Sportswriters in Chicago introducing spicy vernacular slang were among the earliest to juice up reporting on games and box scores. Earlier narrative accounts resembled a dull stock market report. In 1886-87 journalists Horatio Seymour and Peter Finley Dunne covering the White Stockings observed that pitchers faced west in Chicago’s West Side Park. Lefties did so with their “south paws.” Expressing bias against left-handers promoted the argot that “south paws” were balmy, or “cockeyed,” “corkscrew-arms,” “twirly thumbs.” In 1871 a “Chicago Score” referred to shutting out the losing team. (There was no New York or Boston Score.) In 1891 to be “Chicagoed” meant vanquished, beaten out of sight, skunked on the field of play. bjb

INTRODUCTION

- Urban Chicago and the National Game by Laurent Pernot

- Chicago Baseball Parks Before 1900

- Spreading The Language of Baseball

PHOTO GALLERY

- Tangled Mass of Boys at West Side Baseball Game

- Street Ball West Side

- Baseball Parks West Side

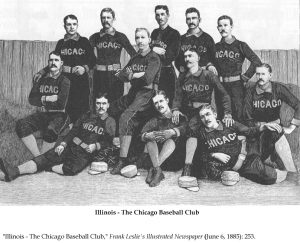

- Local Baseball Clubs and Players

- Baseball on Popular Magazine Covers

CHICAGO PLAYER BASEBALL CARDS

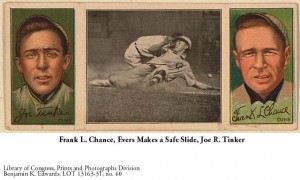

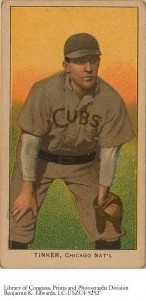

Baseball in the nineteenth century strived to make itself into a respectable professional sport from a rowdy pick-up game. Photography assisted in raising the game to a visual spectacle especially for younger fans. As part of a campaign to sell products, advertisers in the decades after the Civil War began marketing popularly branded consumer goods by including color-printed trade cards in the package. The practice took off, and professional baseball followed suit. “To see was to believe.”

Sponsored first by tobacco companies, baseball cards featured uniformed players from winning teams in iconic batting and fielding poses with tools of the trade (bats and gloves) in hand. The first cards were included as a premium stiffening a pack of cigarettes. They were quickly valued as collectibles especially by youth. In the realm of the visual, the new-found glamour of baseball reciprocated by enhancing the glamour of the manly use of tobacco.

Chicago with its winning teams and large fan (”fanatic”) base was a major market for transforming the previously casual ball game into a major industry with celebrated heroes. As a viewing experience, the Joe Tinker card of the Tinker to Evers to Chance combo “knocked it out of the park.” The front side of a baseball card featured a player, the back side often information about the player branded with the company’s commercial trademark and logo.

The success of the marketing strategy quickly attracted confectionery (candy) companies, especially caramel products, to produce and distribute sets of trade cards as prizes in boxes. An instance was the popularity of the caramel covered popcorn in Cracker Jacks in Chicago in 1914–“the more you eat the more you want.” With the rapid proliferation of baseball cards, the marketing message became, “the more you see the more you want.” Take me out to the old ball game! bjb

“CHICAGOED”: BASEBALL GLOSSARY

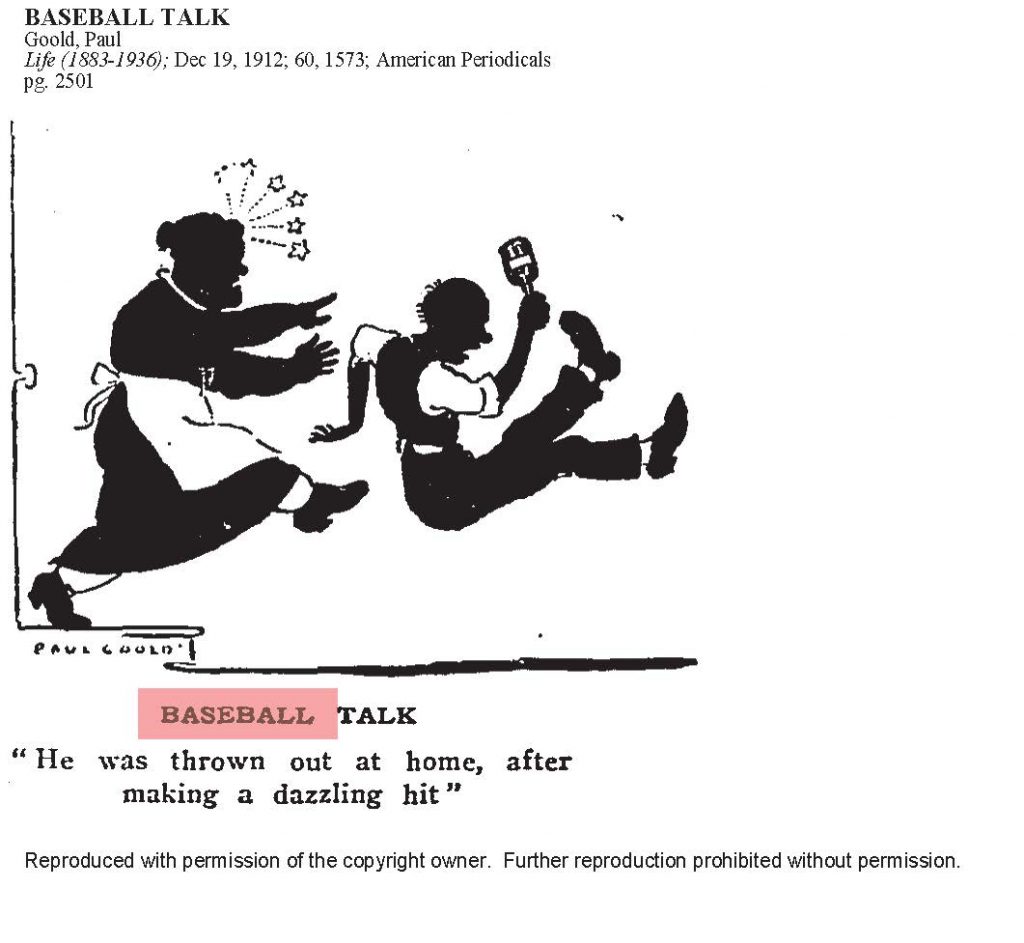

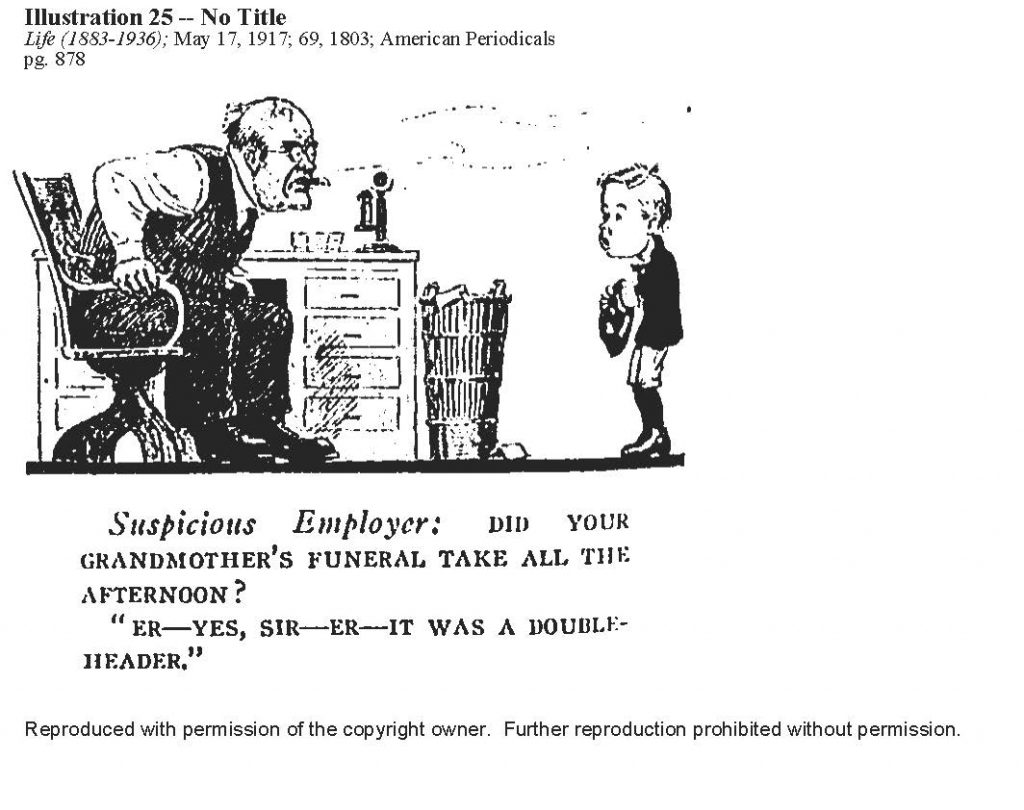

The ever growing vernacular male slang of American baseball expressed felt-realities shared in a polyglot urban environment of diverse nationalities, ethnicities, religions, and races where “keeping one’s eye on the ball,” “hitting a home run,” not “striking out” or getting “shut out (Chicagoed)” described attitudes in the everyday world of ordinary living where one “stepped up to the plate,” “went the distance,” and was “thrown out.”

The vernacular of baseball was for the most part generational. A first generation of Jews in the ghetto, for instance, commonly spoke only Yiddish not English, while they rejected baseball as a frivolous waste of time. Unlike their parents, bi-lingual children became Americans by learning to speak a slangy American vernacular prevalent on the neighborhood streets and in the playgrounds. bjb

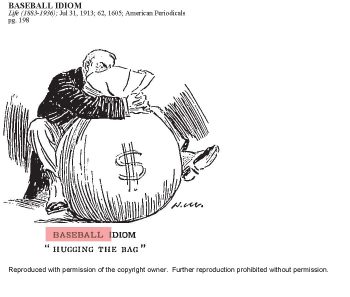

BASEBALL “TALK” IN LIFE MAGAZINE: POPULAR CARTOONS (1889-1913)

- In Training-Life (1889)

- Baseball Term-Life (1894)

- Baseball Term-Life (1897)

- Baseball Term-Life (1902)

- Baseball Term1-Life (1909)

- Baseball Term2-Life (1909)

- Baseball Term1-Life (1910)

- Baseball Term2-Life (1910)

- Baseball Term3-Life (1910)

- Baseball Suggestion-Life (1911)

- Baseball Term-Life (1911)

- Baseball Term-Life (1912)

- Baseball Talk-Life1 (1912)

- Baseball Talk-Life2 (1912)

- Baseball Talk-Life3 (1912)

- Baseball Talk-Life4 (1912)

- Baseball Talk-Life5 (1912)

- Baseball Term-Life (1912)

- Baseball Term5-Life (1912)

- A Baseball Fan-Life (1913)

- Baseball Idiom-Life (1913)

- Baseball Talk-Life1 (1913)

- Baseball Talk-Life2 (1913)

- Baseball Term-Life (1913)

- Baseball Term3-Life (1913)

- Baseball-Life (1913)

- Watching The Bulletin-Puck (1913)

BASEBALL AN URBAN RELIGION

Morris Raphael Cohen was born in Imperial Russia, and at age twelve moved with his family to the U.S. in 1892. He was educated at City College of New York (the proletarian’s Harvard) where he taught Philosophy for many years.

In response both to his orthodox Jewish home traditions and his secular urban childhood, Cohen was pragmatic about what it would take to unite diverse peoples in a common activity in industrial and commercial cities like New York and Chicago. Political pleadings for community, shared sacrifice, and the public good–refrains from a nativist older generation–were insufficient to motivate and convert skeptical and cynical urban populations to join in a common objective.

Professional baseball, in which the objective was winning, had proven itself as more than a mere game. From sand lot to ball park, from immigrant child to working-class adult, the sport of professional baseball displayed an awesome identification with a higher power, a mystic unity with a larger life. “Is there any other experience in modern life in which multitudes of men so completely and intensely lose their individual selves in the larger life which they call their city?”

Baseball with its rules embodied adversarial combat on a fair field of battle–a moral equivalent of war. With the long baseball season, the large number of games, the importance of statistical averages such as RBIs and ERAs–there was always another time at bat to anticipate, another inning to play, another game to win or lose, another penant race, another season to play. Consolation today, work for a better outcome. In 1919, after the human carnage on the First World War’s battlefields, Cohen’s moral equivalent of war argument pitched the ball into the strike zone. bjb

- Morris Raphael Cohen (1880-1947)

- An Urban Religion, Moral Equivalent of War by Morris R. Cohen (1919)

BASEBALL PRIMERS: 19th CENTURY

“How To” primers proliferated in the reading marketplace in the mid-19th century. When Mark Twain signed on as a cub pilot on the shape-shifting and treacherous Mississippi River, his mentor handed him a notebook and guiding maps with instructions to start learning the indeterminate snake-like river as he had learned his “ABCs.”

With the rising popularity of ball games, both in the countryside and cities, English-born American sportswriter Henry Chadwick began producing “how to” primers for the evolving game of Base Ball. He elaborated upon the features of the game with multiple illustrations, detailed descriptions, precise measurements of the playing field, and methodical guiding rules. A statistician, Chadwick was the first to rely on the centrality of numerical evidence, box scores of runs and home runs, strikeouts, batting averages and earned run averages, all essential features of the modern professional game.

With a sense of the sensational, Chadwick promoted himself as the father of the national sport. He described his achievement as an “entering wedge” and “powerful lever” in a “great reformation” by which regular people would be “lifted into a position of more devotion to physical exercise and healthful outdoor recreation.”

His objective was to lay out a disciplined form of “moral recreation” which could be played almost anywhere by any person with inexpensive equipment and minimal fear of bodily injury from wild pitching, brawling players, and imperious umpires. bjb

- Henry Chadwick (1824-1908)

- How To Learn The Game by Henry Chadwick-1st book (1868)

- How To Learn The Game by Henry Chadwick-2nd book (1868)

- How To Learn The Game by Henry Chadwick-3rd book (1868)

- Rules and Regulations (1868)

- Chadwick’s Baseball Manual (1874)

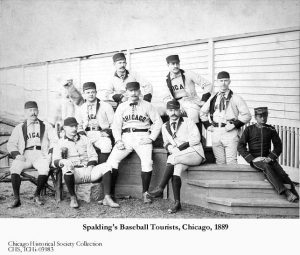

ALFRED G. SPALDING, CHICAGO

Celebrated as the father of baseball, Albert Goodwill Spalding dedicated most of his career contributing to the professionalization and development of “America’s game.” He believed sports built character and furnished a wholesome antidote to the late nineteenth century’s urban industrial ills.

Spalding was born in 1850 in Byron, Illinois to financially prosperous parents. After his father died in 1858, Albert lived with his aunt in Rockford, Illinois, where he attended public school and later Rockford Community College. His career in baseball began at the age of twelve when he participated in informal town games in a local schoolboy club.

When a new baseball club formed in 1865 called the Forest Cities, Spalding was asked to join as pitcher. By 1867 he became well known when the Forest Cities defeated the Washington Nationals. He was first employed as a clerk for one of the baseball team’s players. At the time the National Association of Baseball Players prohibited players being paid salaries.

In 1870 Spalding became a professional player and joined Harry Wright’s newly created professional league, the National Association of Professional Baseball Players. He was captain and pitcher for the Boston Red Stockings. The team subsequently won four championships between 1872 and 1875. In five years with the Red Stockings, Spalding won 205 games and became identified as the “champion pitcher of the world.”

In 1876 to left Boston to pitch for and manage the Chicago White Stockings. While building Chicago’s professional baseball team, Spalding also aided in transforming baseball into a respectable and popular pastime for rural and urban young Americans alike. Spalding quit pitching in 1878 and became a full-time team and business manager. In 1882 he was named president of the Chicago White Stockings, and remained until 1891. He assisted in creating the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs now with standardized rules and means of enforcement.

At the same time he opened A. G. Spalding and Brothers Sporting Goods in Chicago, including the manufacture and vending of baseball equipment. The company expanded and profited from Spalding’s name recognition and influence, and became the exclusive provider of baseballs for league players, and publisher of the Official League Book. Spalding himself edited Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide from 1878 to 1880. The Spalding enterprises also manufactured equipment for other sports, including footballs, basketballs, and golf clubs, becoming the best known sports equipment company of its time. bjb

- The Psychology Of Baseball by A.G. Spalding (1911)

- America’s National Game by Albert .G. Spalding (1911)

BILLY SUNDAY, EVANGELICAL ATHLETE

Billy Sunday was a popular outfielder known for his speed and agility in the National League in Chicago. When he converted to evangelical Christianity at Pacific Garden Mission at 386 S. Clark Street in the 1880s, his life took a new direction. Born into poverty in Iowa of German immigrant parents (name Sonntag Americanized to Sunday), Billy’s father died serving in the Civil War, and the boy was raised in a series of orphanages. He shifted around in odd jobs when his athletic ability was spotted and he was signed by A.G. Spalding’s Chicago White Stockings in the National League. Over an eight year baseball career with major league teams, his hitting was average, fielding good, and base-running first-rate.

Following the encounter with salvation at the Mission on Clark St., Billy decided to sacrifice a $3500. baseball salary to work at the YMCA for $83 per month, while developing his skills as a pulpit evangelist. Also he now renounced drinking, swearing, and gambling–all inveterate habits of his working-class professional baseball player circle of friends.

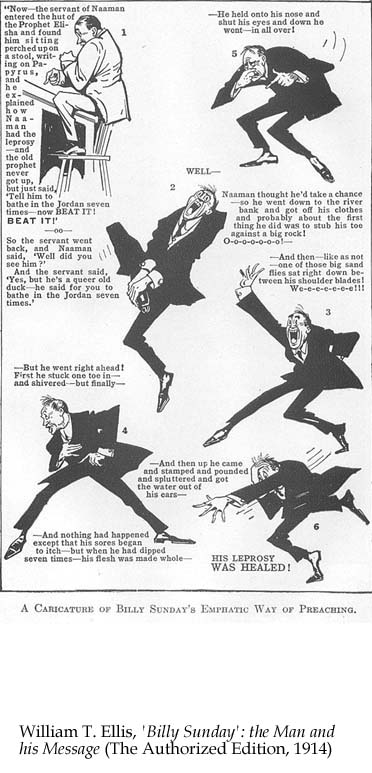

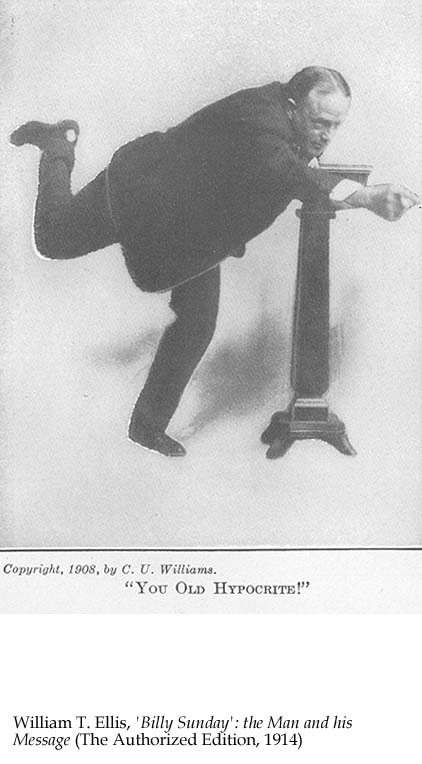

In the early decades of the 20th century Sunday’s unique style of fire-drenched sermons and frenzied acrobatics–stretching and racing to snare and catch sinners as he once had leaped and dived to catch baseballs and speed around the bases–made him the nation’s largest drawing revivalist preacher on the “saw dust” trail. Churches that were too small to hold the crowds turned to tents, and midwestern towns not electrified prompted Sunday to refer to his circuit as the “kerosene trail.” Every limb animated, Sunday circled around the stage, throwing out his arms and feet gesturing a slide into home base.

With his ministry expanding, Sunday’s wife became his campaign manager. The family operation was now transformed from a casual free-will offering road show into a profitable business hiring song leaders, a music director, advance men, Bible teachers, set-up workers, and support staff for outreach evangelization.

Fireworks and slangy sermonizing were the new brand for saving souls, an extravagant style of hell-fire gloom that many main-line religionists found raw, disgusting, improper, indecent, and depraved. But all that mattered was that evangelical sinners in the pliable and gesticulating hands of Billy Sunday approved their spiritual fate in large numbers, an estimated one hundred million face to face before the era of electronic amplification. Scandal never touched Billy Sunday.

It all began for a working-class boy on a baseball field in Chicago and in a rescue Mission on South Clark Street. Over the years, Pacific Garden Mission was relocated several times in the city to serve and shelter transient and homeless populations. Today it is located at 14th Place and Canal Street, about a mile southwest of its original State Street site. bjb

- Billy Sunday (1862-1935)

- Billy Sunday’s Urban Religion by Stephen A. Brown

- Pacific Garden-Mission in the Slum (1904)

- The Devils Boomerangs or Hotcakes on the Griddle

BILLY SUNDAY EVANGELICAL PREACHER: GALLERY

- Billy Sunday Preacher in Action

- Father Knickerbocker Hears Billy Sunday

- Christening Billy Sunday Style