CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

HULL-HOUSE “OASIS” IN A SLUM

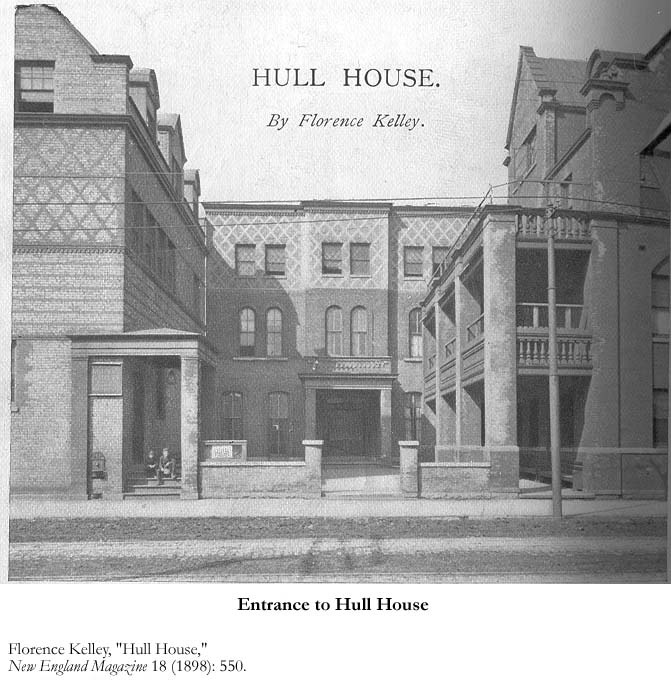

When Charles Hull stood on the steps of his new mansion at Polk and Harrison streets, he took in a view of the city from what was a suburban fringe of Chicago. The vast acres to the east stood unoccupied with only the faint visages of streets outlined on the prairie. Even Halsted Street at his doorstep was unpaved and minimally traveled.

The noise, congestion and smells of the commercial district to the north and the lumber district to the south were far removed. Here, on the steps of his mansion, he thought to watch his Chicago grow. Looking at an 1855 map of his city, Hull had selected an area devoid of neighbors. The large blocks of land were not divided and subdivided like those closer to the heart of the city. Here, he was certain, others would follow in his footsteps. All in all, it seemed the perfect site for his new brick mansion and he would profit from the land boom.

Charles Hull would soon have neighbors, but not the kind he had envisioned. He did not know that the nature of the neighborhood would change almost overnight. In pre-Fire Chicago, the rich lived side by side with ‘middling’ folk and neither would ever be very far from the poor.

The population of Chicago in 1855 was 31, 783 with 6000 Irish, 5000 Germans, 2000 English, 1000 Scotch and 500 from Southern Europe, a combined 22% from abroad. By 1860, the population had expanded to 109,206 with a foreign-born element of 55,000 or 50%. The majority of these newcomers were living in Charles Hull’s front yard. European immigrants began to arrive in substantial numbers during the late 1850s. On one day alone in 1857, over 3400 arrived from New York. Some passed further on to the western prairie, but many remained, found jobs and settled into warrens and patches extending westward across the unoccupied land, right up to Charles Hull’s doorstep.

By the time of the Civil War in 1861, the Near West Side was a continually changing neighborhood of unemployed, working poor and a rapidly emerging, upward-bound middle class. Life in the nineteenth century was precarious, fragile even for the well-to-do. Hull’s wife died in 1860, and his son died in the cholera epidemic in 1866. The Hulls were soon gone from the neighborhood. In the 1870s the Mansion became a home for the elderly run by the Little Sisters of the Poor. In the 1880s it became a boarding house and warehouse when Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr first rented it in 1889. bjb

INTRODUCTION: AN EVENT CALLED HULL-HOUSE

- An Event Called Hull-House

- Daily Life at Hull-House

- Activities at Hull-House

- Music at Hull-House

- First Ladies of Hull-House

- Evolution of the Idea of a Settlement House

HULL-HOUSE ON HALSTED: PHOTO GALLERY

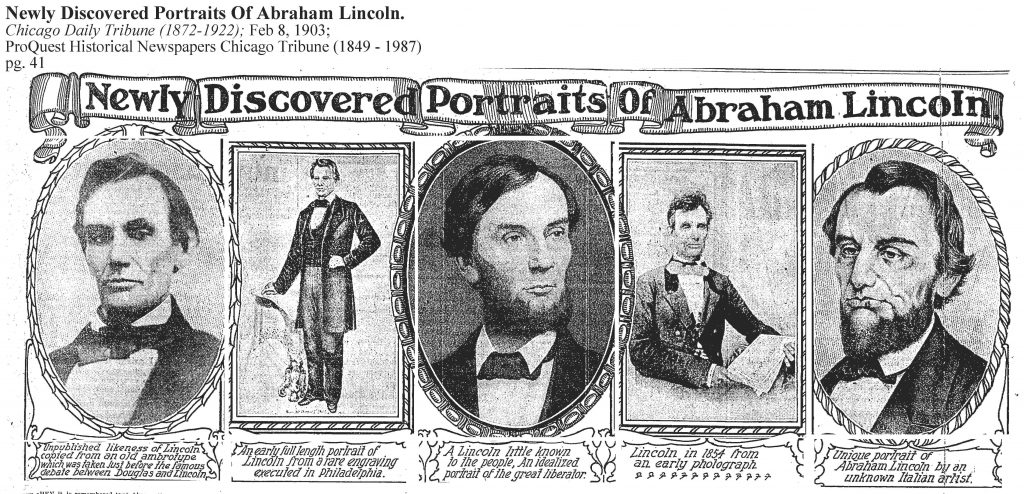

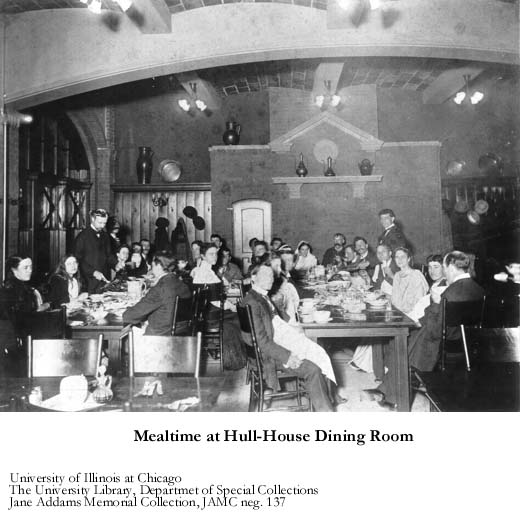

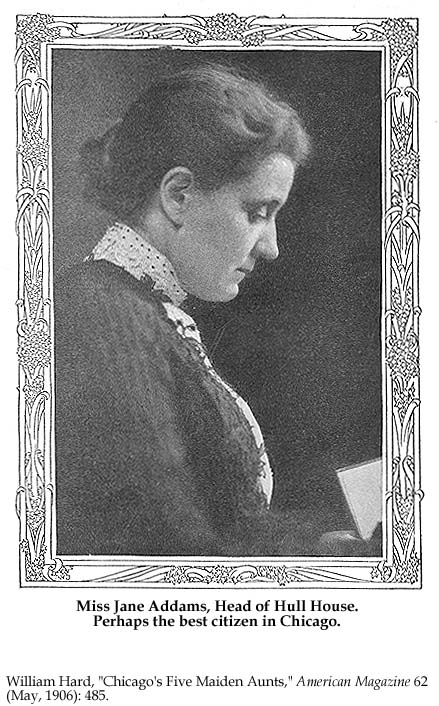

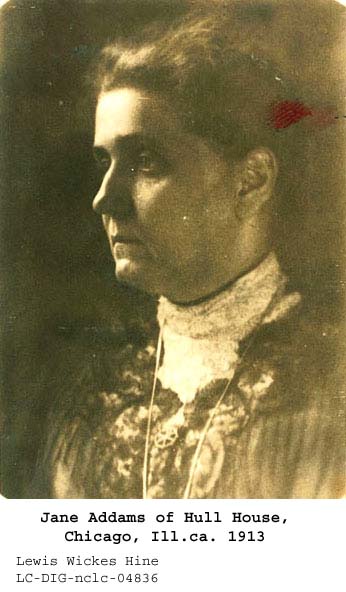

An essayist and publicist, Jane Addams presumed that photography and imagery could establish a lasting public impression. Graphic forms had the capacity both to influence public opinion and frame public knowledge. Jane Addams, for one, admired the photographic portraits of Abraham Lincoln, first published in the 1890s, placing his character and maturity at a younger age on public display.

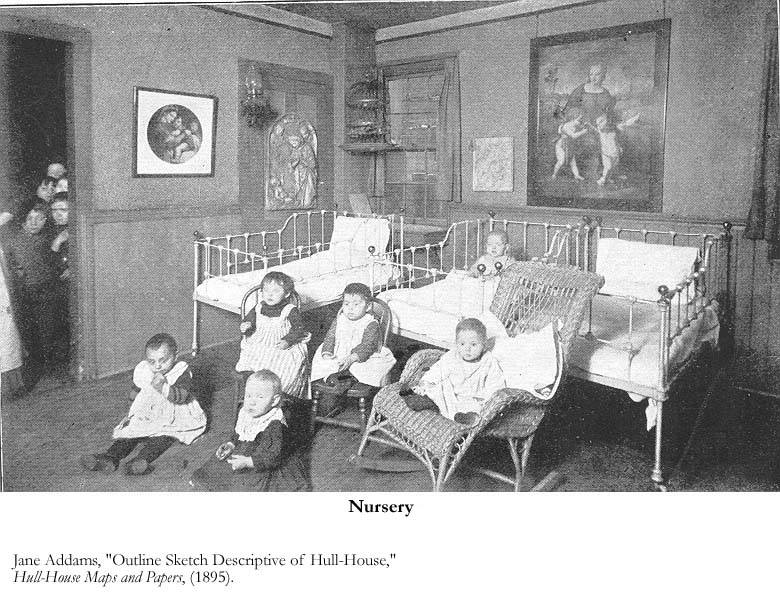

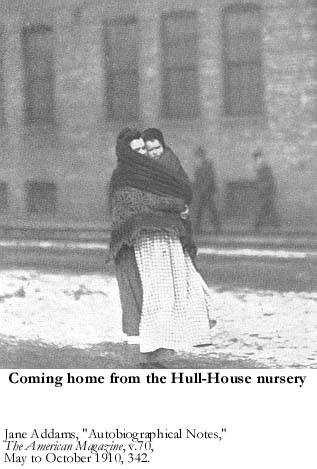

The camera was a lasting presence at Hull-House from its early years, picturing the Settlement’s activities as uplifting models of education and enlightenment within the dark Chicago “slum.” Jane Addams believed the images of Hull-House and portraits of her character belonged to everyone as public property in the domain of enlightened civilization. They testified as visual evidence to the female reformer’s good works and noble mission-inspired calling. bjb

- Hull-House on Halsted

- Hull-House Interiors

- Arts Activities at Hull-House

- Child Care-Mary Crane Nursery-Hull-House

- Children Activities at Hull-House

- Hull-House Pictured In The 1890s

- Labor Museum at Hull-House

- Music Activities at Hull-House

- Hull-House Resident Ladies

- Florence Kelley at Hull-House, 1898

- Jane Addams Pictured: Later Years by Wallace Kirkland

SETTLEMENT HOUSE: AN “OASIS” IN THE SLUM (1895-1913)

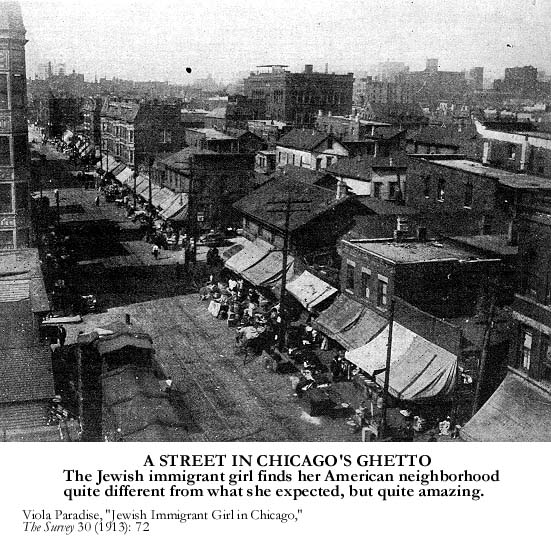

Dirty and densely crowded back streets and alleys with squalid and wretched low-class living conditions, dangerous places overrun by criminals and wickedness–this was the widely publicized nineteenth-century image of the “slum.” In response, an audience of enlightened citizens both was perversely repulsed by the slum as evil and pruriently attracted to it as exotic. On the West Side, Settlement House benefactors publicized Hull-House as an “oasis” in a “moral desert,” a place which nourished life, sprouted beauty and happiness, and permitted the weary to rest. bjb

- An Oasis in Maxwell Street (1895)

- Chicago Five Maiden Aunts, The Women Who Boss Chicago To Its Advantage by William Hard (1906)

- Gives Jane Addams Halo, Calls Settlement Worker a Saint (1906)

- Oasis in Moral Desert, Social Settlement for Center of Saloon District (1906)

- The Best Women in Chicago (1906)

- Day Nurseries of Chicago, Slum’s Oasis of Happiness (1909)

- Chicago is the First City to Establish Social Settlements in its Public Parks (1910)

- Oasis in the City’s Desert Where the “Tired Girl” May Rest (1913)

- See House Beautiful, Chicago Enlightened

- See Alice Hamilton, M.D., Hull-House Physician

“SLUMMING” CLUB WOMEN AND REFORMERS (1906-1909)

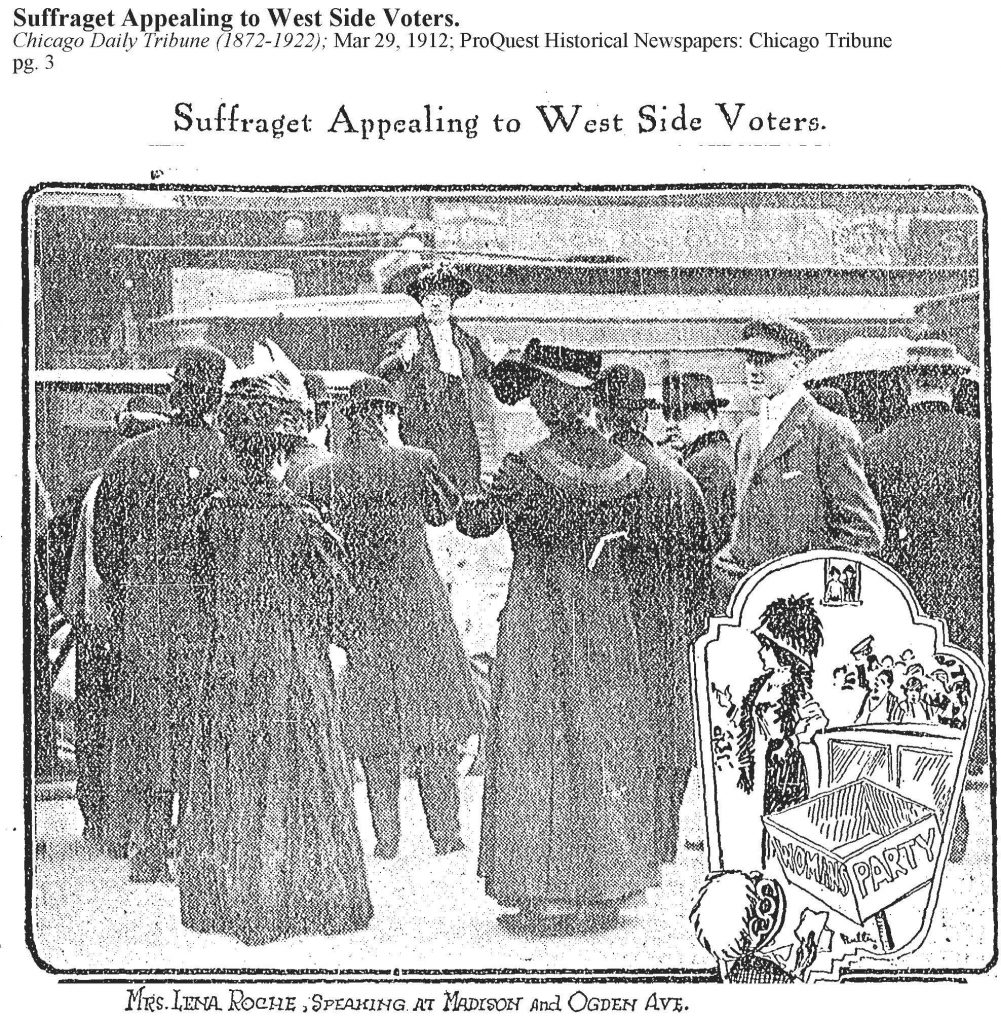

The act of “slumming” or visiting the slime pits of the inner city for philanthropic, disreputable, or amusement purposes began in the 1880s. Club women and reformers were attracted to the philanthropic opportunities, secret adventures, and illicit attractions during excursions to the nether regions of Chicago’s West Side.

Nels Anderson, who grew up on West Madison Street and intimately knew the scene observed that “slumming has become a popular and profitable pastime. Slumming is such a craze, in fact, that it carries through the twenty-four hours of the day. There is the daylight crowd looking for sentiment and souvenirs, the white-light crowd dining in colorful restaurants till midnight, and the red-light crowd burning the candle at both ends till dawn. There is another emotional class who feel that the slum is a sore spot on the body urban, and they hope by organized effort to be rid of it. That is a big order and pathetically naive.”

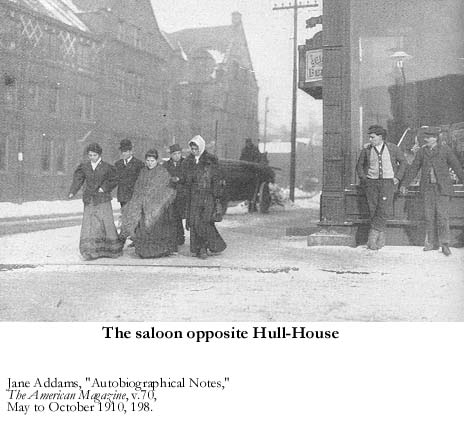

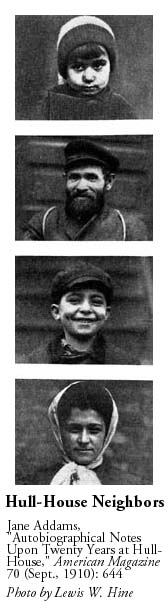

Jane Addams was old school, an aesthetic practitioner of plain dress, physical restraint, and spiritual mastery of character. Indeed, there are no photos of Addams walking on city streets outside the cloistered confines of Hull-House nor any photos of Hull-House residents walking on local streets. A single photo by Lewis Hine of a well-dressed group of three women and two men strolling down Halsted in front of the saloon across the street from Hull-House with two unemployed workers casually standing against the building and eyeing them does not identify the strollers, only the location. Addams who had commissioned the Lewis Hine photo rejected it for the publication of her autobiography, Twenty Years at Hull-House (1910).

- 100 Club Women, Church Workers, and Reformers Unite to Clean Chicago Red Light District (1907)

- Slumming Parties (1907)

- Slumming Trips For Children (1907)

- What We Saw During Our Slumming Tour (1907)

- Fight Migration of Levee Women (1909)

HULL-HOUSE ESSAYS ON THE MAXWELL STREET DISTRICT GHETTO AND SLUM

- Charles Zueblin, “The Chicago Ghetto” (1895)

- Agnes Sinclair Holbrook, “Map Notes and Comments” (1895)

- See Maxwell Street Architecture Tour

HOUSEKEEPING: PERSONAL EXPERIENCES LIVING IN A SETTLEMENT HOUSE

- Wallace Kirkland, Jr., “A Childhood Living at Hull-House”

- Wallace Kirkland, Jr., “Interview with Dr. Wallace Kirkland, Jr.”

- Nicholas Kelley, “Early Days at Hull-House”

- Florence Kelley, “I Go to Work” (1898)

- May Brown Loomis, “The Inner Life of the Settlement”

- Bertha Johnston, “Social Settlement Life in Chicago”

- Jane Robbins, “The First Year at the College Settlement”

- Harriet Rice, “Letter to Miss Jane Addams” (1928)

- Harriet Rice, “Letter to Miss Mary” (1933

HULL-HOUSE NEIGHBORS RESPOND

Not all neighbors were favorable to Jane Addams’s motives and means.

In 1911 McG. wrote Addams in response to the publication of Twenty Years at Hull-House in the following unedited letter:

“Miss Adams: I have been reading in your book called Twenty years at Hull House and I cant make enny thing out of it except that you have a verry high oppinion of Jane Adams and of the mirth of her soul. When you look through the book for enny thing that seems like sympathy you get a lemon. I was a neighbour of Hull House when it first started up and I got help in menny ways especially where I was a member of the Lincoln Club but since it has to be run by capitelists who can afford to give some of the tained money they have squeezed out of there brothers Hull House dont stand for enny thing in particular that counts. I think you started out all right. But you have got off the track. You have tryed to cary water on both sholders and you have got your head turned. Perhaps you will turn back one of these days when you get enough experience. This is the hope of a friend of Hull House 15 years ago.”

Oral History interviews archived in the Hull-House Museum

LABOR MUSEUM AT HULL-HOUSE

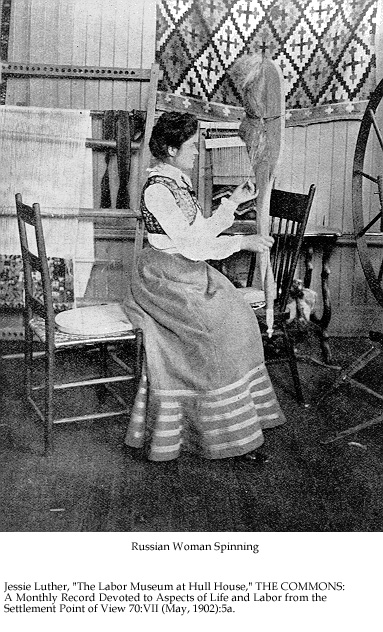

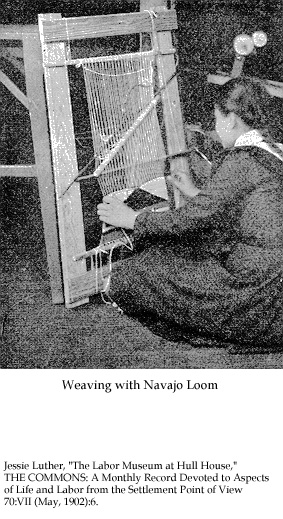

A Labor Museum was originally suggested to Jane Addams by the “Italian Colony” adjacent to Hull-House. Many living older women originally from Italy had “spun and wove the entire stock of family clothing,” and were continuing to twist fiber into thread and spin using “the primitive form of spindle and distaff.” Addams observed that their young and ambitious children working with advanced machines in industrial factories now treated their elders as antiquated, “uncouth and un-American.”

The Museum aimed to restore dignity and draw attention to older picturesque forms of labor, to restore the pride and confidence of youth in their parents skills and their national heritage, and to draw the social connection between the satisfaction of skilled work and the well-being of society. Addams purposely selected the word Museum in preference to School to disassociate it from childish tasks, Albeit the presentation of the Museum would contrive “some fascination of the show” with traditionally costumed workers performing on a stage.

There were six departments in the Museum: Woods, Book-binding, Textiles, Grains, Metals, Pottery. Providing the old people an opportunity to display their craft skills in a Labor Museum, Hull-House hoped to achieve the following:

1. A realization of the “picturesqueness of industrial processes” invested with a “charm” now absent in the “barren” and “monotonous” life of contemporary production.

2. To give the younger generation in shops and factories an appreciation of the physical properties of the materials they were handling, and the steps of production required to make a quality finished product from raw materials.

3. To help the older generation reassert their position in the community to “which their position and training entitle them.” But which they lost because of “lacking in certain superficial qualities too highly prized by the young people.” bjb

- Jane Addams, Labor Museum at Hull-House (1900)

- First Report of a Labor Museum at Hull-House (1901-1902)

- Labor Museum at Hull-House: Photo Gallery

- See Strike, Walkout, Wage and Labor Action

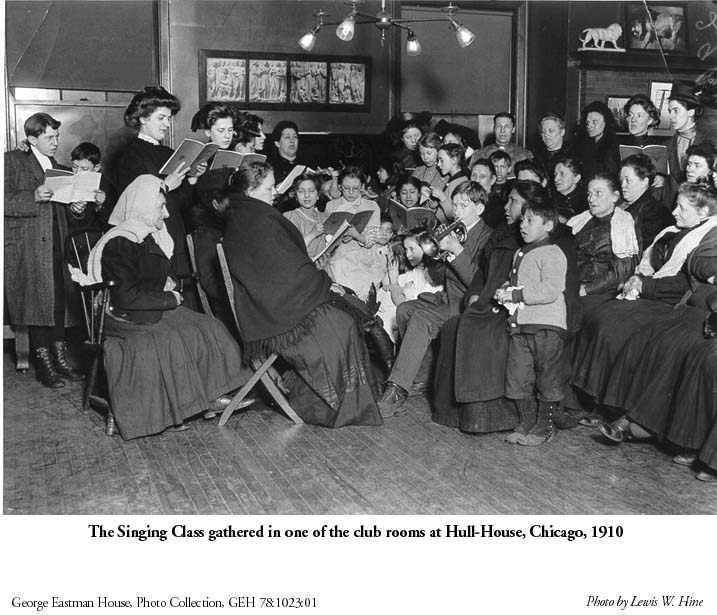

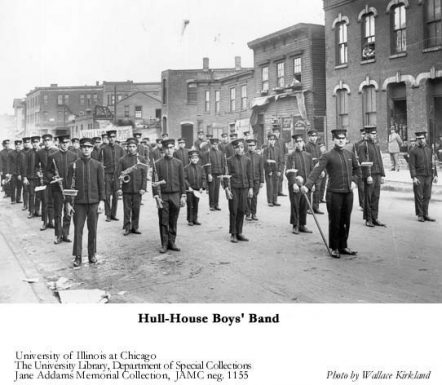

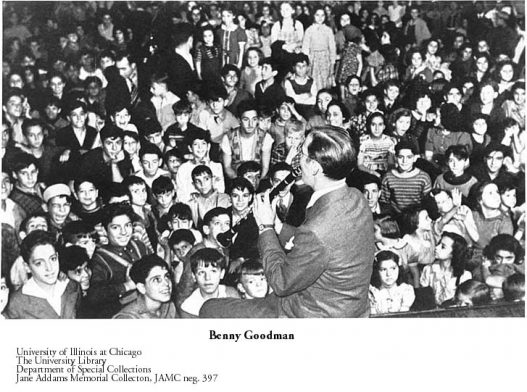

MUSIC AND MUSIC EDUCATION AT HULL-HOUSE

The sounds and evidence of music appreciation and music education, both sacred and secular, were everywhere on West Side city streets. Italians gesticulated when singing Neapolitan songs, Talmudic male Jews swayed and chanted fingering their shawls and repeating the commandments, peddling criers rhythmically shouted out their wares from wagons. Walking the local streets, Theodore Dreiser observed that the “accordion, the harmonica, the Jews Harp, and the clattering tin-pan piano or stringy violin were forever going.” The band leader, Benny Goodman, learned his music in the local synagogue, adapted it in Hull-House, and incorporated the jazz of Chicago’s African-American beat and rhythm to produce a fresh ballroom sound for the increasingly popular and swinging dance floor.

An immigrant in the neighborhood who survived the murderous patriotic nationalism in World War I wrote Jane Addams: “If my countrymen could have seen at the Christmas exercises at Hull-House the little negro boy beside the Mexicans and Italians, all singing together, they would ask, ‘Why has my youth been poisoned? Why did we have to live through hunger, disease, constant yellow fear of death?’ when children of all colors can sing to the same Lord of Peace, at Hull-House.” bjb

HULL-HOUSE BOY’S BAND

BENNY GOODMAN KING OF SWING AT HULL-HOUSE

PHOTO GALLERY

HULL-HOUSE “WAR” AGAINST “VICIOUS AMUSEMENTS”

INTRODUCTION

JANE ADDAMS

LOUISE de KOVEN BOWEN

- Louise Bowen Biography

- Dance Halls (1911)

- Public Dance Halls in Chicago (1912)

- The Road To Destruction Made Easy In Chicago (1916)

- See “Defective” — “Delinquent” Children: Reformers

HULL-HOUSE VISITORS, RESIDENTS, AND GUESTS: MIND-SET OF LIBERAL SOCIAL REFORMERS

WILLIAM STEAD, IF CHRIST CAME TO CHICAGO, Successful British newspaper editor identified with early use of investigative techniques and inflammatory exposes of urban political corruption and cruelty towards the underclasses.

-

-

- Preface

- Part I Chapter 1 – In Harrison Street Police Station

- Part I Chapter 2 – Maggie Darling

- Part I Chapter 3 – Whiskey and Politics

- Part I Chapter 4 – The Chicagoan Trinity

- Part I Chapter 5 – Who are the Disreputables?

- Part I Chapter 6 – The Nineteenth Precinct of the First Ward

- Part V Chapter 5 – Who is my Neighbor

- Part V Chapter 6 – In the 20th century

-

BEATRICE WEBB, British Fabian socialist, sociologist, economist, labor historian and social reformer who coined the term “collective bargaining”

JOHN DEWEY, American philosopher of “Pragmatism” and instrumental leader at the University of Chicago in formation of fields of Progressive Education and Social Psychology. Visitor and participant at Hull-House. “The School as a Social Center” was a seminal and influential essay with fresh perspectives on reforming teaching techniques and curriculum selection in struggling urban schools with mandates for compulsory attendance.

WILLIAM HARD, Hull-House resident in 1902.

WILLIAM W.D.P. BLISS, clergyman, social gospel reformer, labor union member, and advocate of the collective ownership of means of production in socialism as the economic spirit and ethical ideal of Christianity.

FRANCIS HACKETT, Irish born and educated writer, moved into Hull House in 1906 and taught English to Russian Immigrants.

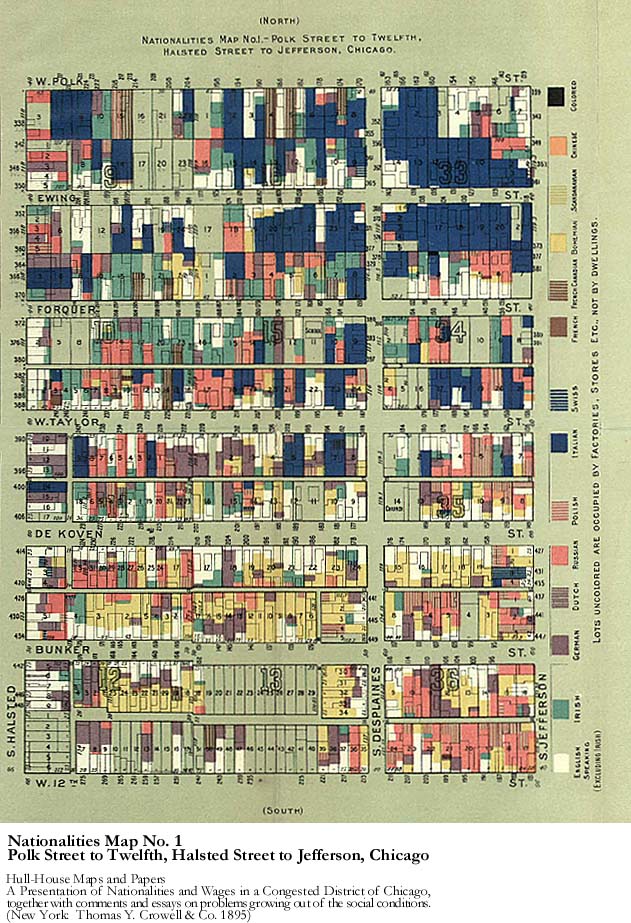

HULL-HOUSE MAPS AND PAPERS: A PRESENTATION OF NATIONALITIES AND WAGES IN A CONGESTED DISTRICT OF CHICAGO (1895)

In the early years after the founding of Hull-House in 1889, Jane Addams was less focused on poverty and social conditions in the district than in promoting lectures and forming group activities at the fledgling Settlement House. Florence Kelley from a very different background had other concerns. In 1892 the Commissioner of Labor appointed her in Chicago, Illinois special agent for an investigation of slums including four major cities, Baltimore, Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia Only nineteenth-century Chicago in the Midwest was not in its origins an eighteenth-century walking town on the eastern seaboard.

After Kelley and her cohort of social workers surveyed tenement residences, block by block, family by family, apartment by apartment did the idea of a book emerge. Multi-color coded maps highlighted the specific findings of wages and nationalities on streets circumscribed as a “slum” adjacent to Hull-House. Between the high cost of producing the linen maps and the limited audience for such an innovative work, the publisher with letters of endorsement in hand proceeded with the publication but with no enthusiasm. There was no second printing. bjb

- See The Slums: of Baltimore, Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia by Carroll D. Wright

- Hull-House Maps and Papers (1895)

INTRODUCTION

NATIONALITY & WAGE MAPS (1893-1895)

SCHEDULES FOR SPECIAL AGENTS (1893-1895)

JANE ADDAMS “AUTOBIOGRAPHY,” AMERICAN MAGAZINE, PHOTO BY HINE (1910)

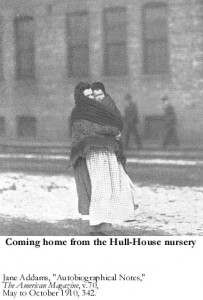

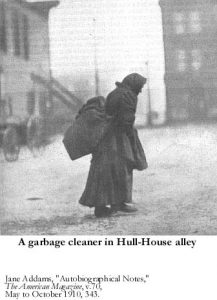

In the Fall of 1910, Macmillan & Co. published Jane Addams’s signature book, Twenty Years at Hull-House: With Autobiographical Notes. Addams began to publish the early chapters of her prudently fashioned autobiography in 1906 in the Ladies Home Journal, a housekeeping magazine brimming with advertisements featuring status-conscious women intimate with the proper furnishing of a well-provisioned middle-class home.

Ladies Home Journal was an odd venue for a reformer proposing to build an audience responsive to a progressive agenda. However, with circulation over one million, LHJ had become the most successful monthly magazine with high production values in the period

As a recognized public intellectual, celebrated female role model, and literary person of contemporary note, Jane Addams pursued the publicist’s opportunity to expand her prominence and visibility as America’s foremost reformer. Richard T. Ely, economist at the University of Wisconsin, testified for her deserved recognition, “a big women who knows the facts …. we need more democratic feeling.”

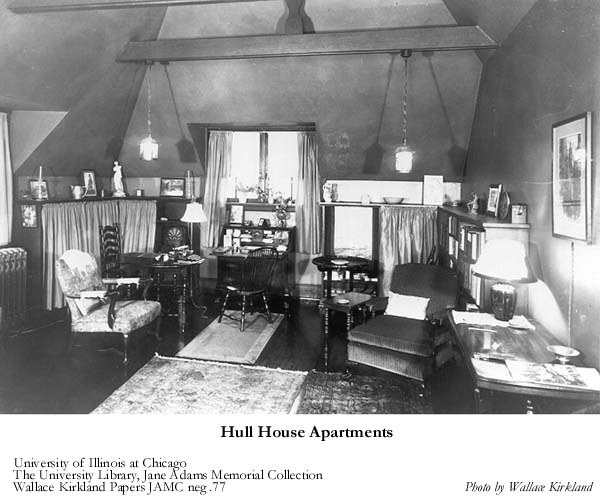

The pictures of Hull-House appearing in the LHJ series of articles were institutional bricks and mortar, a material built environment. Hull-House projected itself as a city on a hill, reaching skyward and towering over the few diminutive persons down below on the street. Slum neighborhood scenes of scuzzy streets, dirty alleys, and impoverished pedestrians were viewed from the protected space inside Hull-House through ornamented glass pane windows.

For the book publication of the Autobiography in late October 1910, Macmillan & Co. in correspondence with Addams agreed with a proposal that the recently launched reform magazine, The American Magazine, publish six chapters “as good advertisement for the book.” Moreover, Macmillan appeared indifferent to the photographs, willing to accept any selection The American Magazine editors and Addams chose to use. In correspondence between Addams and her publishers, the costs of printing photographs, both on full-page glossy pages and on text pages never appeared to be at issue or an obstacle to publication.

The editors of The American Magazine’s decided to commission Lewis Hine for photographs on Chicago’s West Side. Hine knew the area from his earlier time in 1900-1901 when working at the Parker School and studying at the University of Chicago. Hine the photographer in 1909 was a former school teacher and unknown to the public. Florence Kelley, with ties to Hull-House and Hine’s mentor Frank Manny, had recently praised Hine in print for his “ingenuity” as a “young photographer.”

In spring and summer of 1910 several months prior to the hard-cover book publication by MacMillan & Co. at the end of October, The American Magazine published the series of Hine’s commissioned photographs on schedule. Hine’s imagery was striking with its realistic detail of neighborhood adults and children going about their daily business on the streets, entering, and inside Hull-House.

However, events now took an unforeseen turn. For the book publication in late October, Jane Addams discarded the Hine photographs. To illustrate drawings in black-line sketches for the hard cover not to distract from the centrality of her written text and her preeminent role at Hull-House, she selected Norah Hamilton, Art Director at Hull-House. Norah, sister to Dr. Alice Hamilton living at Hull-House, had majored in Art at college.

An instructor in art workshops at Hull-House, she became an apostle for the aesthetics of beauty as an essential component in developing personal moral “character.” In an educational setting, the viewpoint was largely shared by Addams. Norah produced fifty-one illustrations for the book publication, only four identified “from a Photograph by Lewis W. Hine.”

Hine’s photographs were shot from perspectives of careering around the streets and alleys around Hull-House, then moving inside to picture club activities for neighborhood boys, girls, and youth. In contrast, Hamilton’s illustrated character sketches were drawn from a cloistered vantage point within Hull-House gazing outside on the neighborhood through the window. She highlighted old-world shtetl village-like stereotypical scenes, reminiscent of Jacob Riis in New York in 1889.

The contrasts between the photographer and the illustrator were arresting. In Hamilton’s drawings, clubs for boys with a billiard table and vocational shops largely vanished. The years following the financial Panic of 1906 until 1911-12 were “hard times” with significant unemployment, rising prices, and “stagflation.” In Hine’s photographs, the tell-tale signs of local street life visibly clung to people attempting to stay warm in their coats and scarves even inside Hull-House. His images were distinctive and memorable. Hamilton’s sketches were bland, faceless, one-dimensional, and forgettable.

A rich narrative remains to be written about Jane Addams’s critical relationship to the power of a graphic visual presentation challenging her commitment to the centrality of her written text. In a case of unintended consequences, a century later Hine’s Chicago photographs remain widely viewed and familiar while Addams’s classic text is generally limited to classroom students of the Progressive Era in American history.

Lewis Hine, forever the School Teacher with a School Camera. bjb

- 1-War Time Childhood

- 2-Snare of Preparation

- 3-Early Undertakings at Hull-House

- 4-Problems of Poverty

- 5-Resources of the Immigrant

- 6-Echoes of the Russian Revolution

- Norah Hamilton Sketches For Twenty Years at Hull House

- Lewis Hine Photographs and Norah Hamilton Sketches

- Presentation: Visual Riddle on Chicago Streets, Jane Addams Rejects Lewis Hine’s Urban Camera by Burton J. Bledstein