CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

LEWIS WICKES HINE

In 1874 Lewis Wickes Hine was born to a shopkeeper family living off Main Street in the hinterland lumber mill town of Oshkosh Wisconsin. As a youth, he received limited schooling graduating high school with a basic learning competence in 1890. In the lower middling class, both sons and daughters were required to work in the economy to support family and themselves. During the onset of the depression years of the early 1890s, the young Hine had little to anticipate, physically demanding manual jobs for which he was only marginally fit, the tedium of part-time clerical chores, and employment layoffs.

Hine’s subsequent work experiences and education included no formal training either in the technologies of photography or in the aesthetics of camera work. Why and specifically how Hine became the prominent photographer of reform in the Progressive era, and the seminal role played by Chicago’s West Side in the development of his urban focus, is best investigated biographically, in the context of the first forty years of his life history.

- LEWIS W. HINE, Origins of a Career, Labor Conditions in an Industrial Hinterland City by Burton J. Bledstein

- Notes

To summarize the fresh idiom of Hine’s visual camera intelligence.

First, moving beyond the studio convention of the angled facial portrait in a studied presentation of character, Hine leveled the street camera eye horizontally. momentarily making direct physical contact with the piercing eyes of his careering subjects. In real world contexts, those eyes flashed back expressing a thicket of crowded feelings including anticipation, amazement, bewilderment, apprehension, fear, hope, confusion. A portrait viewer “reads” the posed face like an artful text. A Hine viewer “encounters” the range of emotions inimitably expressed by the dominating eyes at a moment frozen in camera time. Encounter an Italian girl’s “first day in America,” a child waiting on a bench, multiplied by hundreds of thousands winding their way through the cattle-like pens, inspection halls, and bureaucratic procedures at Ellis Island.

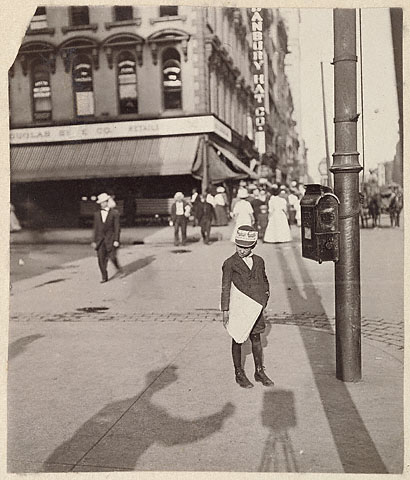

Second, by bringing to light unseen micro-realities hidden behind pictorial facades, the detective or street camera performed as a “stealth” technology in the historical era of the X-ray, the laboratory microscope, smokeless gun powder, and the torpedo killer submarine. By working to minimize distortions in behavior caused by technology’s presence, including an operators’ tell-tale interference, a stealth presence aimed to expose–“to X-Ray”–previously inaccessible evidence beneath the surface. Accordingly, Hine the investigating photographer coveted an anonymous presence on the scene of action, casting a slim imprint on the street with a shadowy outline. In dramatic contrast, Progressive-era reformers such as Jane Addams and her peers favored the revisionist literary genre of Autobiography as the popular medium for self-expression. Their intensely personal retrospective life histories centered on early conversion experiences to a sacred mission of Christian charity and social service. Over time they forged a steely pro-active self-identity essential to a reformer’s adversarial tasks.

Third, “Ever; – the Human Document to keep the present and future in touch with the past.” In Hine’s body of work, temporal perspectives, angles, and positions on a subject of interest were inexhaustible. The sheer production of Hine images seemed interminable. No single image was definitive. None was symbolically exemplary or sole representative of a truth. None was iconic. Imagining the realities of working lives, especially children and youth, the photographer’s visual burden to change public thinking by means of pictures with powerful ideas was a lofty one. When the photograph softened, mellowed, and washed out the texture of harsh conditions and hard times, when it manipulated fakery and lied at the command of special interests, the photographer failed. “While photographs may not lie,” Hine turned the irony on its head, “liars may photograph.”

EARLY INFLUENCE, OSHKOSH WISCONSIN (1898-1900)

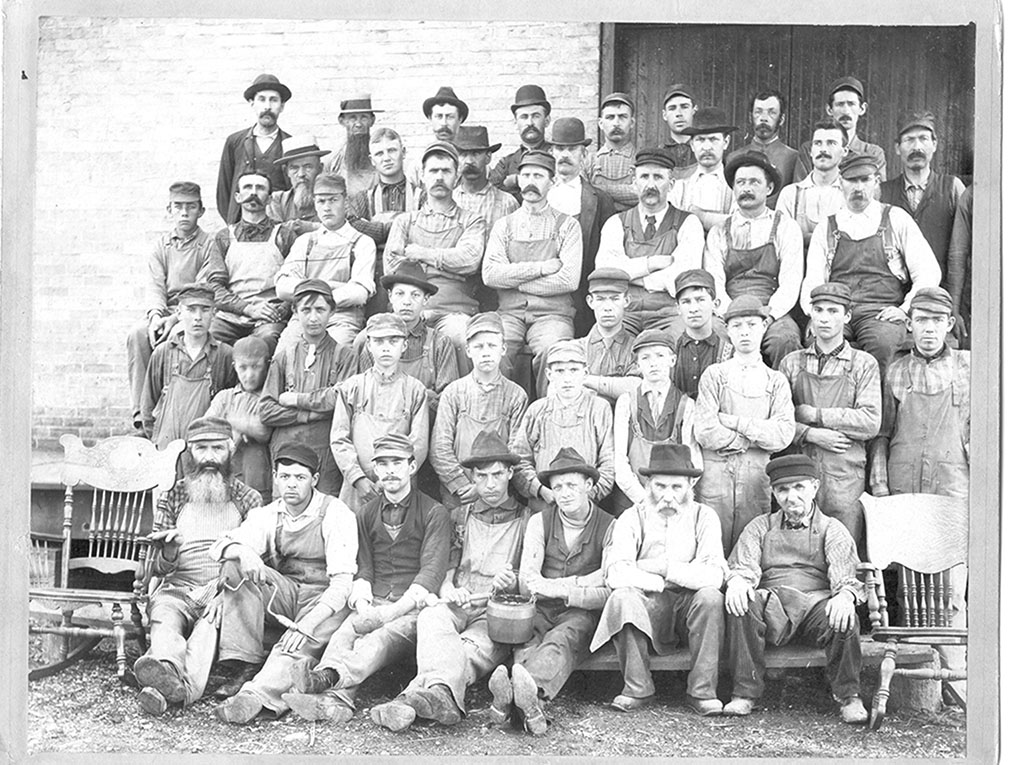

In 1898 the workers’ strike against the Paine Lumber Company in Oshkosh Wisconsin was the earliest major labor action in the state’s history. The Union’s demands were 1. Increase in Wages 2. Abolition of cheap women and child labor 3. Recognition of the Union 4. A weekly pay day.

Not satisfied with defeating the worker uprising, the owners had the director and secretary of The Amalgamated Wood Workers Union arrested on charges of criminal conspiracy to injure the business of the lumber company. If convicted the penalty could be death by hanging, and the precedent would make labor strikes illegal in Wisconsin.

The court case rested on the legality of labor picketing during a strike action. The State charged picketing amounted to conspiracy and the defense claimed picketing was in itself innocent and lawful. This was only the second legal case of its kind on record. The Amalgamated hired Clarence Darrow from Chicago for the defense who asked not for pay but the right to publish the transcript of his unrevised final summation to the court.

Son of a wood worker and Abolitionist family, Darrow in his folksy, devastating sarcasm turned the tables charging the prosecutors and plaintiffs with being the real conspirators serving the Gods of wage slavery, servitude, and mammon. After a three week trial, the jury acquitted the defendants after one hour of deliberation.

Frank Manny and Lewis Hine were physically on site in Oshkosh in the midst of the nationally publicized events. In 1900 Hine followed Darrow’s route on the track back to Chicago to work, study, and live in Hyde Park, Darrow’s neighborhood. This became Hine’s primary encounter with the big city. bjb

PHOTO GALLERY

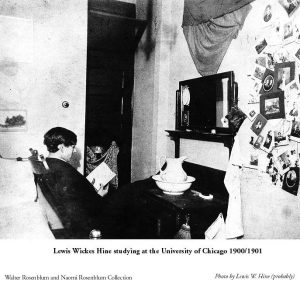

LEWIS W. HINE, TRANSCRIPT NON-DEGREE GRADUATE STUDENT: THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO (1900-1901)

In 1900, by means of his networking and relationships in Chicago, Frank Manny recommended Hine for a paying position at the Parker School in Chicago. Hine credited him in his autobiographical notes:

“[Manny] arranged for me to work my way through the summer school at the new

Chicago Institute, where I studied under Colonel Francis Parker and other very progressive teachers, preparing for special work in teaching nature study and geography in the elementary grades, and taking special courses in Science, Pedagogy, and Education.”

Manny also facilitated Hine’s entrance as an “unclassified” (non-degree) graduate student at the University of Chicago (1900-1901). On his Application Card dated August 11, 1900 Hine listed his primary subject of interest as Geography followed by Botany then History and Pedagogy. He had graduated Oshkosh High School in 1890, and later in the decade attended Oshkosh Normal School. At the age of twenty-six, his family home on Division Street in downtown Oshkosh remained his primary address. In Hine’s words,

“In the fall of 1900 I entered the University of Chicago for a year. Spent half time as clerk in the information office, the rest in classes under such teachers as John Dewey, Ella Flagg Young and a young professor of science and psychology, Dr. Charles C. Adams, who later became Director of New York State Museum, Albany N.Y. He was one of my early teachers of economics.”

These were influential years for scholars and students associated with educational reform. Among Hine’s teachers at Chicago, Thorstein Veblen published Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), John Dewey, The School and Society (1899). At Harvard, William James presented his popular lectures, Talks to Teachers (1899). bjb

- Lewis Hine Transcripts

- Note Transcript

- 1-Summer 1900

- 2-Autumn 1900

- 3-Winter 1901

- 4-Spring 1901

- 5-Summer 1902

PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE SCHOOL CURRICULUM, LEWIS W. HINE EARLY ESSAYS (1906-1908)

Hine noted in 1904 that the ever-experimental “Mr. Manny saw a need for visualizing the school activities (this was in many ways one of the most progressive schools in the country) so he conceived the idea of having a ‘school photographer’ and I was elected to the job.” Hine could not explain why Manny chose him since “I never had a camera in my hand …. But then one of Manny’s chief jobs has always been to X-ray potentialities in the rank and file.”

In his 1899 Lectures in the Philosophy of Education, Manny’s mentor John Dewey had taught, “I think there is not a point in modern psychology that can be so directly helpful to the teacher as the work that has been done in the the study of various forms of imagery.” Now with his school Principal’s avid support and even personal assistance lugging around photography equipment, Hine with his 5 x 7 camera mounted on a wobbly tripod, plunger and magnesium flash powder, and minimal technical knowledge began to take excursions with his classes on field trips, most notably to Ellis Island in 1904.

The “school camera” as a pedagogical tool for investigation, Hine argued, reached into “every nook and corner of school activity.” It produced a tangible record of how things more realistically worked– a working knowledge of “past conditions, changes, and growth.” It would both preserve a record of evidence and use it within a reformed progressive curriculum. “I had long wanted to use the camera for records,” Manny later wrote Hine, “and you were the only one who seemed to see what I was after.”

For Hine, as for the theoretical Dewey, books and classrooms were insufficient. In the “Walk in the Park,” Hine explored the pedagogical value of encountering the larger world of nature. He also took his students around the city photographing economic life, and studying the relationship of the images to their studies.

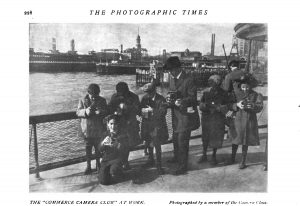

Access to affordable and relatively easy to use cameras–“you press the button we do the rest”–had made them a popular technology. The purpose of the school camera club, Hine reasoned, was to transform impulsive “button pressers” who snap at everything looking for the lucky shot into disciplined, intelligent, and patient amateur photographers. In the school setting, an experienced eye would learn to pick out from the thicket of realities the eventful frames or moments of contrast that made a meaningful difference in the relentlessly swift stream of daily experience.

In the six years Hine dedicated himself to teaching at the Ethical Culture School, four were concerned with his growing passion for the use of the camera. The possibilities were opening to transcend a one-dimensional book education with multi-dimensional visual learning, or “visual thinking.” Hine the student of a progressive education in Chicago now with the school camera became prologue to Hine the progressive era’s most prolific evidence-centered documentary social photographer, albeit a self-trained one. bjb

- An Indian Summer (1906)

- School Camera (1906)

- School In The Park (1906)

- Silhouette In Photography (1906)

- Photography In The School (1908)

IMMIGRANTS AT GATEWAY, ELLIS ISLAND PORT OF ENTRY, PHOTO BY HINE: (1905-1926)

Until 1908, when he left school teaching to become a professional photographer, Hine noted that “I carried on this visualizing of the school and at the same time made many trips to Ellis Island, and into the tenements and streets where the underprivileged lived.” He had his students photograph nature and also the economic life of the big city. In the classroom the students studied the images and related them to the curriculum.

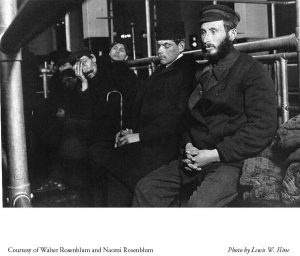

After he left Oshkosh and as his career developed, Hine became a “traveling man.” People at work in motion–coming, leaving, moving about–focused the attention of his camera eye. Opened in 1892, the gateway Ellis Island in upper New York Bay was the busiest Port of Entry inspection station for migrants and travelers to the northern tier of East coast and Midwestern states. As a public institution, Ellis Island was a perpetual motion machine.

Herded through cattle-like barriers in a great room illuminated by glaring electric lights, immigrants passing through were subjected to invasive questioning by record-keeping agents, an intrusive medical inspection, observation to determine feeble-mindedness, hospitalization on the Island if not detained for deportation, and waiting rooms for sponsors usually family to pick up anticipating arrivals. When bound for inland destinations like Chicago a shuttle system transported passengers to the special immigrant terminal at the railway station.

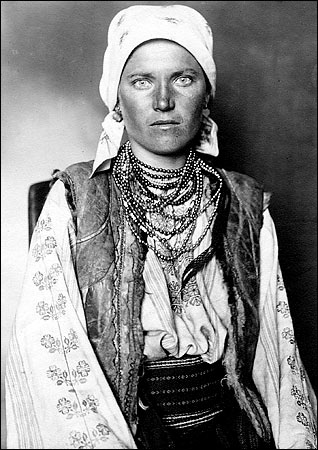

By processing thousands of new arrivals every working day, the activity on the island in 1904 was a panoramic visual spectacle. Nineteenth-century illustrated conventions pictured the “aliens” as dumb peasants good only for manual labor or brutalized devil-take-the-hindmost vagabonds (gypsies) best to deport. Augustus Sherman, a clerk in the Island bureaucracy, assumed the duties of institutional photographer, massing over two hundred images. In his Island studio, he encouraged his subjects to dress up in their most elaborate national folk costumes, jewelry and all, which intensified the pictorial impression of a wave of exotic adventurers, both glamorous and mysterious, invading American shores.

On a field trip, school teacher Hine’s interest on the crowded working floors of the Island differed from Sherman’s rigidly posed studio portraits. The school photographer was encumbered by awkward flash equipment and now had the task of getting nervous adults and fidgeting children to stand still long enough to snap the shudder.

In a letter Hine detailed the obstacles presented by his maiden excursion to Ellis Island:

“We are elbowing our way tho the mob at Ellis (Island) trying to stop the surge of bewildered beings oozing through the corridors, up the stairs and all over the place, eager to get it all over, and be on their way. Here is a small group that seems to have possibilities so we stop ’em and explain in pantomime that it would be lovely if they would only stick around for just a moment. The rest of the human tide swirls around, often not to considerate of either the camera or us. We get the focus, on the ground plate, of course, then hoping they will stay put, get the flash lamp ready …. Meantime, the group had strayed around a little and you had to give a quick focal adjustment, while someone held the lamp. The shutter was closed, of course, plate holder inserted and cover slide removed, usually, the lamp retrieved, then the real work began. By that time, most of the group were either silly or stony or weeping with hysteria because the bystanders had been pelting them with advice and comments, and the climax came when you raised the flash pan aloft over them and they waited, rigidly, for the blast. It took all the resources of hypnotist, a supersalesman, and a ball pitcher to prepare them to play the game and then to outguess them so most were neither wincing or shutting eyes when the time came to shoot. Naturally, everyone shut his eyes when the flash went off but the fact that their reactions were a little slower than the optics of the flash saved the day, usually.”

Looking past the conventions of the facial portrait and finery, Hine leveled the camera eye horizontally making contact with the eyes of his shabby dressed subjects who stared back. Those eyes in constant and rapid motion talked back to Hine’s camera eye by expressing a thicket of crowded feelings: apprehension, anticipation, bewilderment, promise, fear, hope. What have I done? Is coming to America the mistake of my life? What is going to happen to me?

As the eyes related, every immigrant’s personal history was in a state of flux. The trajectory of an immigrant’s career was less than predictable. Being an immigrant was more than a social category, represented by continuous series of portraits mounted on museum walls. Caught by Hine’s school camera, being an immigrant was a cognitive concept identified by a spectrum of intimate personal responses. In contrast with Sherman’s “face-minded” portrait likenesses or Joseph Stella’s artistic character studies in Americans in the Rough (1905), Hine’s “eye-minded” photographs were “Ever the human document.”

A fresh idiom, a pejorative form of visual slang to the artistic purists, Hine’s first body of photographs lacking technical sophistication gave a new direction to perspectives on the social experience of common working people, wherever they came from.

At the turn of the twentieth century, political controversy fomented by nativists, racists, and eugenicists were inflaming public opinion. An “unfit” and “undesirable” lot of immigrants speaking foreign languages and living foreign lives were arriving in significant numbers from impoverished lands of Central and Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean, and Asia. Were they “mongrelizing” an Anglo-American (Nordic) cultural purity? Were they polluting the “great white race?”

Or were they building the prospects for a diverse nation’s future strengths? All Americans after the eighteenth century except arguably indigenous peoples were hyphenated or impure–German-American, Irish-American, Italian-American, Greek-American, including white Anglo-American. Most all came from modest to lower working class backgrounds–a piece of family history and self knowledge conveniently blinkered out by latter-day ultra nationalists, “patriots,” and America-first propagandists. bjb

- As They Came to Ellis Island (1908)

- Ellis Island: General Statement by Lewis Hine (1905-1926)

- Photo Gallery: Lewis Hine at Ellis Island 1905-1926

- The Old World In The New (1914)

- Americans in the Rough: Character Studies at Ellis Island by Joseph Stella (1905)

- Ellis Island Studio Photographs by Augustus Sherman 1906-1912

- Passing of the Great White Race by Burton J. Bledstein

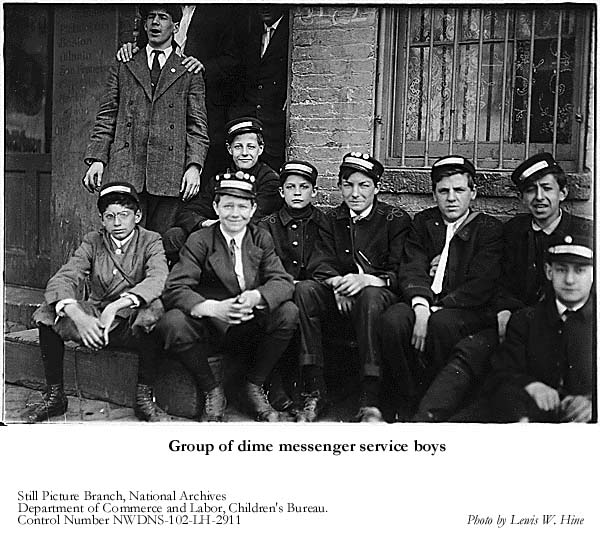

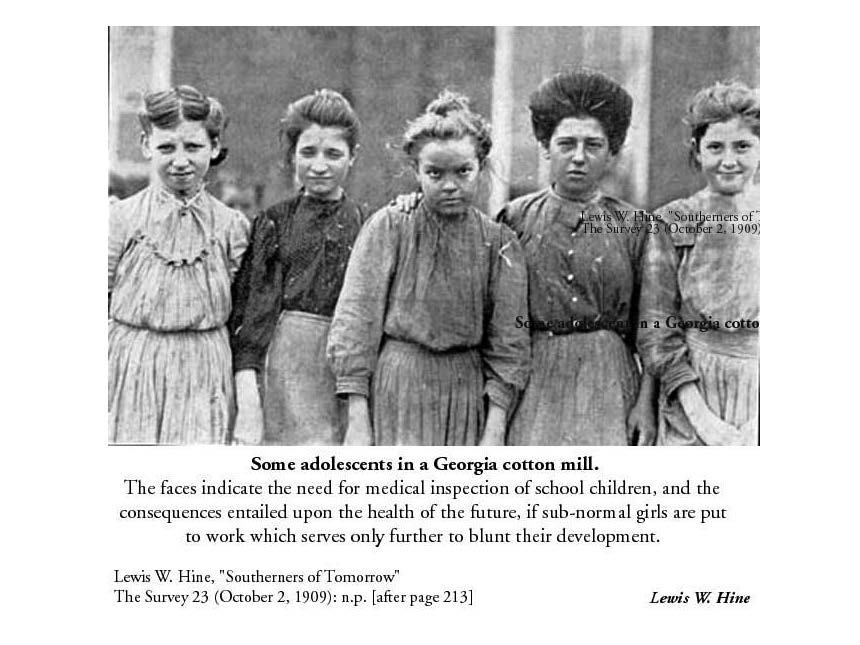

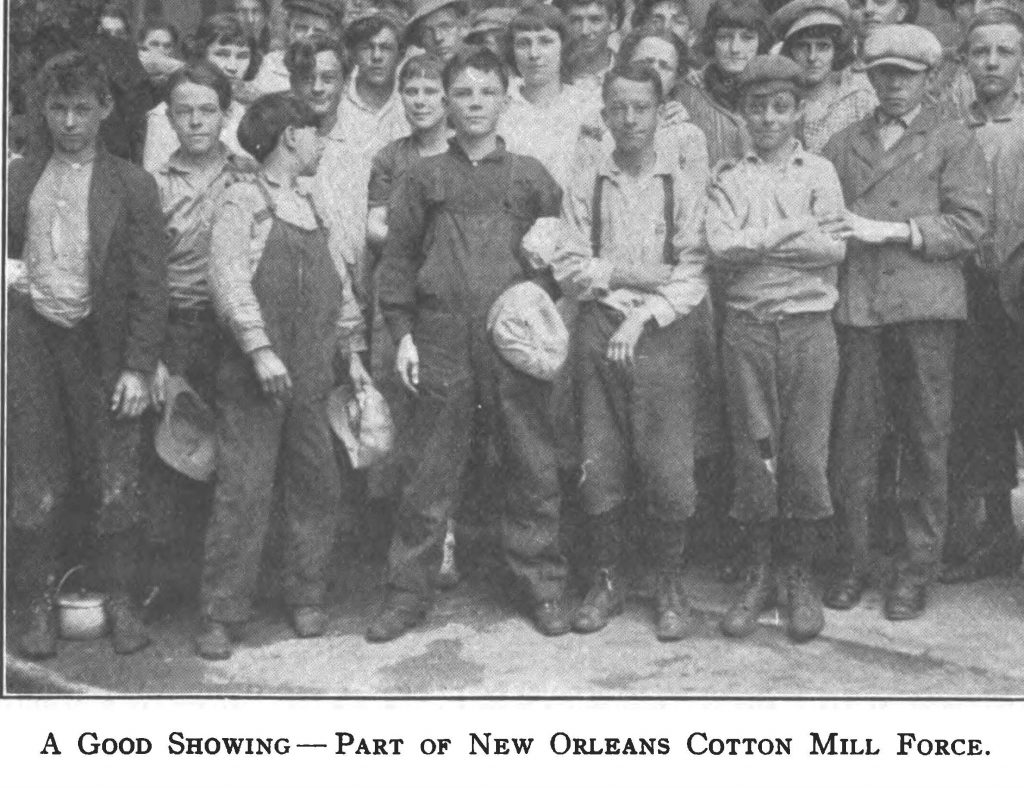

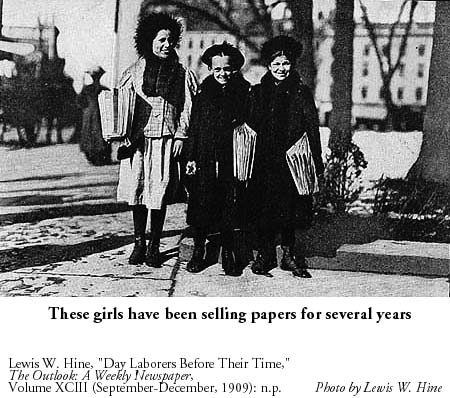

NATIONAL CHILD LABOR COMMITTEE: “PHOTOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION” BY LEWIS HINE (1906-1914)

Following the period at the University of Chicago, Lewis Hine became a teacher at the Ethical Culture School in New York City. Continuing to depend on his salary from teaching, in 1906 he picked up part-time work traveling as a free-lance photographer for the National Child Labor Committee. It commissioned pictures primarily to ornament lengthy written reports and proceedings and and to mount exhibits. Publicity from photographs and visual presentations was intended to generate a higher profile for the social work organization, an objective which proved difficult to attain.

The inner circle of the NCLC leadership was indifferent when not hostile to photographs, diminishing them as picturesque distractions from the real story presented in detailed charts and columns of numerical findings. As staff photographer, Hine’s role in his own words was “as sort of a handyman for social welfare conventions and the like that wanted some bare walls filled up.” A hired hand at NCLC, he often did not receive credit for his prolific work visualizing actual children at laboring tasks on city streets, in work places, and southern mills.

In 1909 the social work journal, Charities and The Commons, soon to be renamed The Survey, published Hine’s first extended photo-story “Child Labor in the Carolinas” “Some Human Documents.” The byline credit went to A.J. McKelway of the NCLC inner circle. The lead photographer remained a background figure, largely anonymous. Florence Kelley, a known critic of the use of photos as sensationalist distractions from the weight of statistical and expert knowledge, agreed to pen the introduction.

Kelley’s response was startling. In the “ingenuity of a young photographer,” she stated, the “camera carried conviction” serving to mobilize public opinion when the presentation of the text, numerical charts, and reams of data did not. The irony was not lost on Hine, who later commented, “by the impetuous and imperious Florence who until I brought in that load of bacon, had ‘no use whatever for photographs in social work.’” In 1910 Hine wrote, “my child labor photos have already set the authorities to work to see ‘if such things can be possible.’ They try to get around them by crying ‘fake’ but therein lies the value of data & a witness.”

In his subsequent work as a full-time photographer, Hine established the use of his “realistic” photographs in a fresh vernacular graphic expression in contrast to “the fuzzy impressionism of the day” prominently displayed in the quarterly photographic journal Camera Work published by Alfred Stieglitz from 1903 to 1917.

Hine’s portable camera, hidden beneath his coat in the mills, was a stealth technology bringing to light hitherto dark and private spaces contradicting the glossy presentations by corporate interests of industrious and happy workers. Photographing laboring children, Hine knew what he was up against in his battle of wits against the industrial capitalist as “guardian” of “special privilege.”

Professional reputation came to the fore, and Hine fended off accusations of being a “sneak” and practicing the “deceptions” of a low-life voyeur. Employers were not about to allow cameras to which they did not consent inside work places, especially when they were profiting greatly by cheap child labor. Respectable public citizens including reformers among the club women were very nervous about the privacy rights and accused Hine of violating the proprietary interest of newspaper publishers, even mill-owners, in their own hired labor.

Sensitive to the criticism and his own reputation for veracity and professional honesty as a photographer, Hine noted in response: “One thing made me extra careful about getting data 100% pure when possible. Because the proponents of the use of children for work sought to discredit the data, and especially the photographer, we used,–was compelled to use the utmost care in making them fire-proof. One argument they did use, ‘Hine used deception to get his child-labor photos, naturally he would not be relied to tell the truth about what he found.’”

On this troubling issue Hine answered: “I have to sit down, ever so often, and give myself a spiritual antiseptic,–as the surgeon before and after an operation. Sometimes I still have grave doubts about it all. There is need for this kind of detective work, and it is a good cause, but it is not always easy to be sure that it all is necessary.” Concerned that the moral criticism of his conduct would undermine his efforts with the NCLC, Hine elaborated further in a handwritten letter to a supportive friend:

“Very early in the game I called on the strong arm in charge of the newspaper delivery room of NY American to ask if he would permit me to make some shots there …. When he barked back at me,–‘Whadoyou want ‘em fer?’ I began to think ‘if I tell him all the truth, he will never agree to it … when he roared, ‘don’t lie to me,–what’s the truth?’ I did not get the shots. After that I always had a water-proof, non-sinkable reason thought out in advance when trying to outwit the guardians of such special privilege as we were up against.”

In 1909, Hine concluded, “the photograph has an added realism of its own. It has an inherent attraction not found in other forms of illustration.” The added realism led Hine to make a distinction between the reformer’s category of “Child Labor” as invariably negative, harmful, and exploitative and the teacher’s concept of “Working Children” or children who work. The latter receive some training and education at a stage in their personal history of growing up.

In 1908, his early insecurities and responsibility for a family weighing on him, Hine made the emotionally difficult decision to resign his teaching position with its secure income to be full-time at NCLC. In his notes on early influences, Hine commented that “it means too much to give up all those years of training without consideration, but it has done its work, perhaps,–at least some work.”

Later Hine reflected, “Followed child labor for nearly twenty years – through the Carolinas, Canneries, Homework, Glass and Textiles, Beet and Cotton-fields, – all from Coast to Coast. All through, – Investigation and Research loomed large, – the photography involving difficult situations with personalities and light conditions. Ever; – the Human Document to keep the present and future in touch with the past.” bjb

- Photo Gallery: Child Labor or Working Child

- Introduction to Lewis Hine Child Labor Photos by Florence Kelley (1909)

- Child Labor in the Carolinas by A.J. McKelway (1909)

- Child Labor in Gulf Coast Canneries Photographic Investigation by Lewis W. Hine (1911)

- The High Cost of Child Labor by Lewis W. Hine (1914)

- High Child Labor Standard in a Great City by Lewis Hine (1914)

“SOCIAL PHOTOGRAPHY” BY LEWIS HINE (1909)

Before an audience of social workers in 1909, Hine delivered his seminal address on “Social Photography: How the Camera May Help in the Social Uplift.” Hine identified himself as a “public educator.” Photography was a tool in the educator’s box of techniques to motivate and assist learning by raising formerly dark, private, concealed, and hidden activities into the light of day for a public audience to witness.

Advertisers and “enterprising manufacturers” had previously realized the sympathies afforded by the camera to clients . Social workers as teachers needed to overcome their doubts and highbrow convictions against imagery. By use of the camera bringing to the surface social conditions of working servitude–the newsie under the city bridge at 3am, the child spinner in the mill–“the public will know what its servants are doing, and it is for these Servants of the Common Good to educate and direct public opinion. We are only beginning to realize the innumerable methods of reaching this great public.”

By eliminating non-essential and conflicting interests, Hine continued, the “picture” tells a story in a “most condensed and vital form.” Often it is more persuasive than direct reality itself. Hine observed that the photograph “had an added realism of its own, an inherent attraction not found in other forms of illustration.” The visual image on a photo plate focused the mind as a “light writer” in the campaign to expose dark places of human exploitation of labor. These shadowy areas were deliberately concealed from public viewing with claims of privacy and “none-of-your … business” by industrial and corporate moneyed interests, for instance factory owners and newspaper syndicates.

Hine cautioned that the“camera we depend on contracts no bad habits.” The average jury of persons must have no reason to doubt the photograph as evidence produced by an investigation. Solid enough as evidence to enter a court of law, the photo as document would be supported by “records of observations, conversations, names and addresses.”

Hine concluded: “I think we should apply the same standard of veracity for the photograph that we do for the written word.” “I try to do with the camera,” Hine later claimed, “what the writer does with words.” Good honest writing may be unappreciated, but “a picture makes its appeal to everyone. Put into the picture an idea, and if properly used, it may be transferred to the brain of the worker.”

Placing the burden of proof for truthfulness on the “social photographer,” Hine set a high bar between manipulated fakery and the trustworthy image which an informed public could believe. “While photographs may not lie,” he framed the irony, “liars may photograph.”

Hine concluded that the realistic social photograph generating in viewers responses of personal disgust and popular indignation could be a powerful lever for reform of working conditions and working lives. Seeing would be believing. Currently unknown in the industrial world, “social photography” would address “the urgent need for the intelligent interpretation of the world’s workers.” bjb

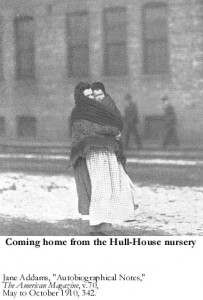

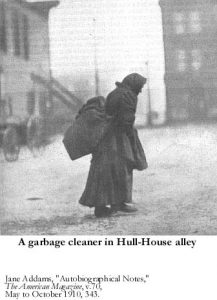

JANE ADDAMS “AUTOBIOGRAPHY,” American Magazine, PHOTO BY HINE (1910)

In the Fall of 1910, Macmillan & Co. published Jane Addams’s signature book, Twenty Years at Hull-House: With Autobiographical Notes. Addams began to publish the early chapters of her prudently fashioned autobiography in 1906 in the Ladies Home Journal, a housekeeping magazine brimming with advertisements featuring status-conscious women intimate with the proper furnishing of a well-provisioned middle-class home.

Ladies Home Journal was an odd venue for a reformer proposing to build an audience responsive to a progressive agenda. However, with circulation over one million, LHJ had become the most successful monthly magazine with high production values in the period

As a recognized public intellectual, celebrated female role model, and literary person of contemporary note, Jane Addams pursued the publicist’s opportunity to expand her prominence and visibility as America’s foremost reformer. Richard T. Ely, economist at the University of Wisconsin, testified for her deserved recognition, “a big women who knows the facts …. we need more democratic feeling.”

The pictures of Hull-House appearing in the LHJ series of articles were institutional bricks and mortar, a material built environment. Hull-House projected itself as a city on a hill, reaching skyward and towering over the few diminutive persons down below on the street. Slum neighborhood scenes of scuzzy streets, dirty alleys, and impoverished pedestrians were viewed from the protected space inside Hull-House through ornamented glass pane windows.

For the book publication of the Autobiography in late October 1910, Macmillan & Co. in correspondence with Addams agreed with a proposal that the recently launched reform magazine, The American Magazine, publish six chapters “as good advertisement for the book.” Moreover, Macmillan appeared indifferent to the photographs, willing to accept any selection The American Magazine editors and Addams chose to use. In correspondence between Addams and her publishers, the costs of printing photographs, both on full-page glossy pages and on text pages never appeared to be at issue or an obstacle to publication.

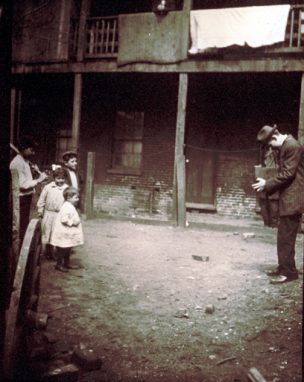

The editors of The American Magazine’s decided to commission Lewis Hine for photographs on Chicago’s West Side. Hine knew the area from his earlier time in 1900-1901 when working at the Parker School and studying at the University of Chicago. Hine the photographer in 1909 was a former school teacher unknown to the public. Florence Kelley, with ties to Hull-House and a friendship with Hine’s mentor Frank Manny, had recently praised Hine in print for his “ingenuity” as a “young photographer.”

In spring and summer of 1910 several months prior to the hard-cover book publication by MacMillan & Co. at the end of October, The American Magazine published the series of Hine’s commissioned photographs on schedule. Hine’s imagery was striking with its realistic detail of neighborhood adults and children going about their daily business on the streets and both entering and inside Hull-House.

However, events now took an unforeseen turn. For the book publication in late October, Jane Addams discarded the Hine photographs. To illustrate drawings in black-line sketches for the hard cover edition which would not distract from the centrality of her written text and her preeminent role at Hull-House, Addams selected Norah Hamilton, Art Director at Hull-House. Norah, sister to Dr. Alice Hamilton living at Hull-House, had majored in Art at college.

An instructor in art workshops at Hull-House, Norah had become an apostle for the aesthetics of beauty as an essential component in developing personal moral “character.” In an educational setting, the viewpoint was largely shared by Addams. Norah produced fifty-one illustrations for the book publication, only four identified “from a Photograph by Lewis W. Hine.”

Hine’s photographs were shot from perspectives of careering around the streets and alleys around Hull-House, then moving inside to picture club activities for neighborhood boys, girls, and youth. In contrast, Hamilton’s illustrated character sketches were drawn from a cloistered vantage point within Hull-House gazing outside on the neighborhood through the window. She highlighted old-world shtetl village-like stereotypical scenes, reminiscent of Jacob Riis’s “how the other half lives” in New York in 1889.

The contrasts between the photographer and the illustrator were arresting. In Hamilton’s drawings, clubs for boys with a billiard table and vocational shops largely vanished. The years following the financial Panic of 1906 until 1911-12 were “hard times” with significant unemployment, rising prices, and “stagflation.” In Hine’s photographs, the tell-tale signs of local street life visibly clung to people attempting to stay warm in their coats and scarves even inside Hull-House. His images were distinctive and memorable. Hamilton’s sketches were bland, faceless, one-dimensional, and forgettable.

A rich narrative remains to be written about Jane Addams’s critical relationship to the power of a graphic visual presentation challenging her commitment to the centrality of the written text. In a case of unintended consequences, a century later Hine’s Chicago photographs remain widely viewed and familiar while Addams’s classic text is generally limited to classroom students of the Progressive Era in American history and Norah’s sketches lost to memory.

Lewis Hine, forever the School Teacher with a School Camera. bjb

- 1-War Time Childhood

- 2-Snare of Preparation

- 3-Early Undertakings at Hull-House

- 4-Problems of Poverty

- 5-Resources of the Immigrant

- 6-Echoes of the Russian Revolution

- Norah Hamilton Sketches For Twenty Years at Hull House

- Lewis Hine Photographs and Norah Hamilton Sketches

- Presentation: Visual Riddle on Chicago Streets, Jane Addams Rejects Lewis Hine’s Urban Camera by Burton J. Bledstein

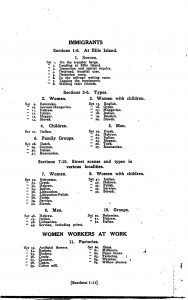

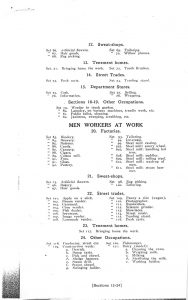

HINE PHOTO COMPANY: CATALOGUE OF SOCIAL AND INDUSTRIAL PHOTOGRAPHS (circa 1912)

“Keep this catalogue for future reference. Our collection is growing. Supplements to our catalogue are issued from time to time. KEEP THIS!–IT IS A KEY to thousands of our negatives from which we make photographs, slides, and enlargements.” The catalogue was distributed for commercial purposes. Presenting a coherent body of work it declared Hine’s urban photography for sale.

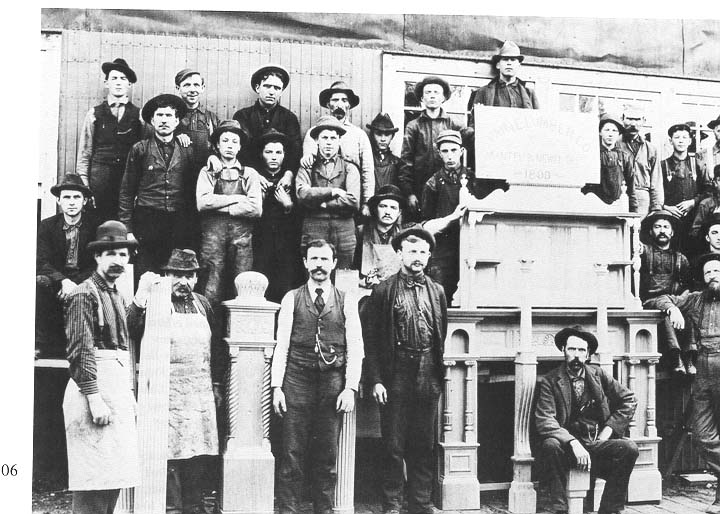

Enumerating a web of topics, sub-topics , and sub-subtopics in urban settings, the Catalogue detailed the complexity of Hine’s vision and the range of his human interests. The city experience was non-linear, each photo documenting a specific “reality” from a shifting and temporal perspective. Frozen at a moment in time, the image spoke to the context in which things were done, and how the city appeared to function–from the point of view of working people not city hall.

No single photo among the 800 plus listed in the expanding Hine body of work was iconic, like an original work of art. Each was a document contributing to a pluralistic narrative of urban encounters. The varieties of peoples and cultures, the spectrum of differing work environments, the disparities between social classes, the strains between male and female roles and work obligations, the dramatic assortment of housing and home arrangements, the types of exploitation including child labor, sweat shops, and prostitution–there were no limits to local differences and diversity in urban life. Seen one example of a work experience, not seen them all, nowhere near!

The visual topics centered on active, historical lives: 1. Immigrants 2. Women workers at Work 3. Men Workers at Work 4. Of Women and Men Workers 5. Incidents of a Worker’s Life 6. Child Labor 7. Child Life 8. Types of Children (Gender) 9. Institutions 10. Institutions 11. Housing 12. The Worker’s Home Life 13. Makeshifts of Poverty 14. Prostitution 15. Amusement 16. The Street 17. View of Various Industries 18. Public Toilets, Disposal of Refuse, Etc. 19. View . bjb

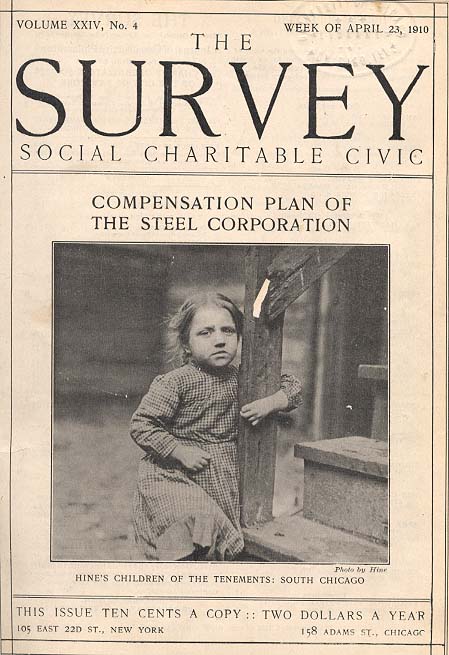

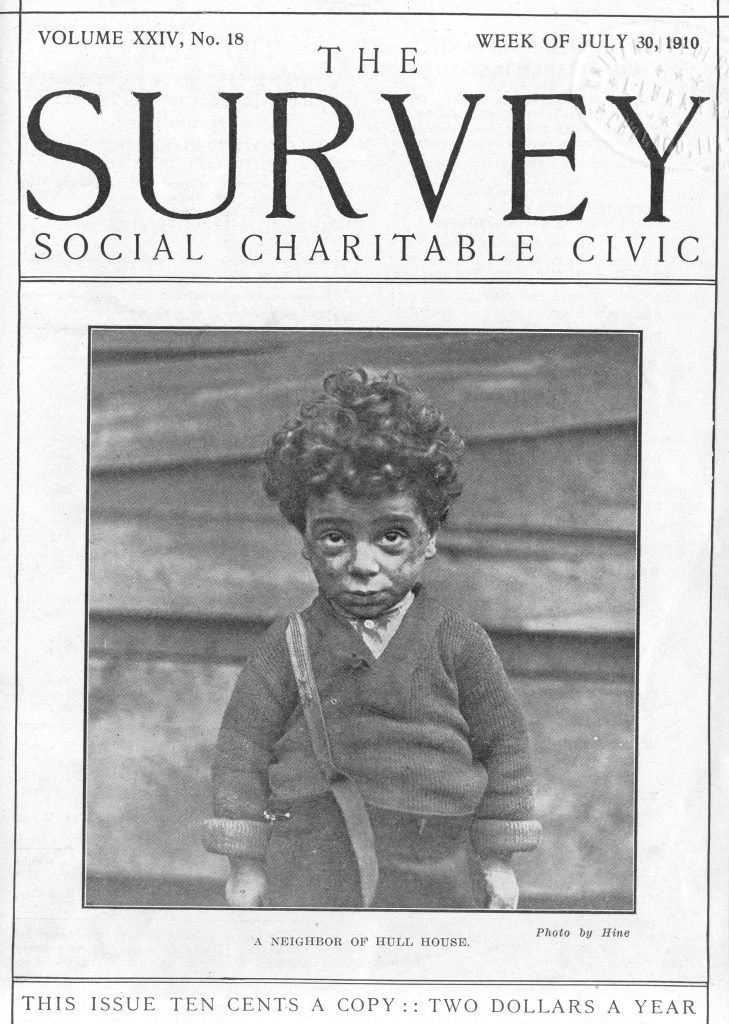

‘THE SURVEY’ MAGAZINE COVERS, PHOTO BY HINE (1910-1912)

In 1897 a modest journal, Charities: A Monthly Review of Local and General Philanthropy began reporting activities of the Charity Organization Society of the City of New York. In 1891 it was absorbed by a monthly, The Charity Review, which was more expansive in geography and scope. And in 1905 it was absorbed by The Commons, the official bulletin of the Chicago Settlement House movement, renamed Charities and The Commons.

The mandate was to cover “industrial justice, efficient philanthropy, educational freedom, and the people’s control of public utilities.” Charities and The Commons became the preeminent publication for the developing profession of social work and social policy. The course of the magazine changed again in 1907 when a new editor was chosen, Paul Kellogg. He affiliated with a massive project, a social survey of working conditions in the city of Pittsburgh, the results of which were first published in the magazine in 1909.

The “Pittsburgh Survey” funded by the Russell Sage Foundation “proposed a careful and fairly comprehensive study of the conditions under which working people live and labor in a great industrial city, and a fair public statement of the facts discovered.” The objective was to accumulate a “body of evidence, such we had never had.”

Kellogg hired an amateur photographer and unknown teacher as staff photographer, Lewis Hine. His assignment was to work largely anonymously visually documenting workers, factories, neighborhoods, and homes. Kellogg’s design for the “survey” was to combine creative research and quality journalism. Statistical data and analysis would end in descriptions of individual case studies, “publicity” would portray the “truth”:

“The idea of graphic portrayal, which begins with such familiar tools of the surveyor as maps and charts and diagrams and reaches far through a scale in which photographs and enlargements, drawings, casts, and three-dimension exhibits exploit all that psychologists have to tell us of the advantages which the eye holds over the ear as a means for communication.”

The word “charity” evoked an older philanthropy and the volunteer efforts by club-women. In 1909 Kellogg proposed changing the name of the charity journal to “The Survey” now better to represent the method and techniques of social work professionalizing as a discipline.

From 1910-1912 multiple images by Lewis Hine of children and workers appeared on the covers of the renamed serial publication. Hine’s images from Chicago were prominently featured. bjb

- 04-16-1910, Volume 24

- 04-23-1910, Volume 24

- 05-28-1910, Volume 24

- 07-30-1910, Volume 24

- 08-20-1910, Volume 24

- 08-27-1910, Volume 24

- 09-10-1910, Volume 24

- 09-24-1910, Volume 24

- 07-8-1911, Volume 26

- 07-22-1911, Volume 26

- 08-12-1911, Volume 26

- 09-16-1911, Volume 26

- 09-23-1911, Volume 26

- 04-6-1912, Volume 28

- 07-29-1912, Volume 28

- 08-24-1912, Volume 28

- 08-28-1912, Volume 28

- 08-31-1912, Volume 28

- 09-14-1912, Volume 28

- 12-16-1912, Volume 28

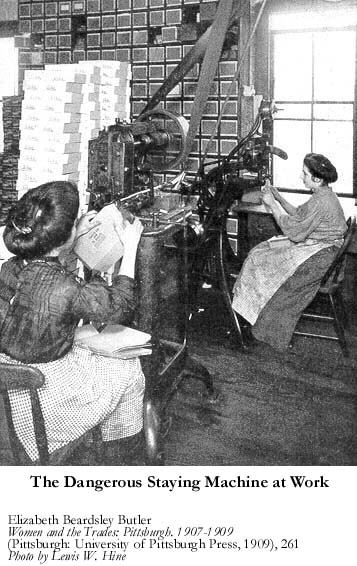

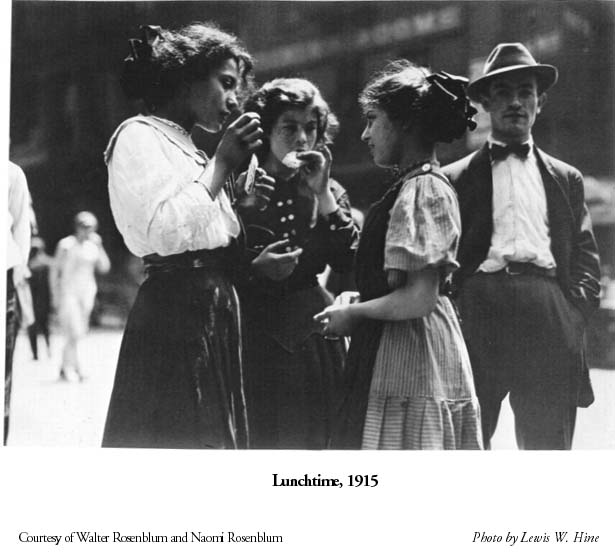

WOMEN IN THE TRADES, PHOTO BY HINE (1909)

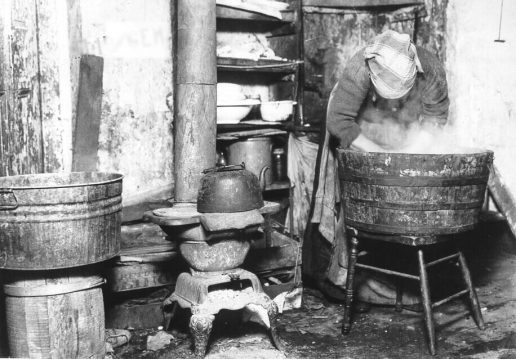

During Lewis Hine’s formative years growing up in Oshkosh, employers, management, and absentee owners relegated work and working people into a shadowy background. Employment by Kellogg and the Pittsburgh Survey now focused Hine’s attention. The camera reaching a large audience, he believed, would bring to light a more realistic and human picture of the conditions under which women in particular but also men worked in the new industrial order. It was a picture largely inaccessible in presentations sympathetic to ownership interests.

In the urban industrial context, both women home workers and factory labor were replaceable parts in a production machine. Inconspicuous and hidden from view, this new labor force often toiled as piece workers for meager wages. Hine pictured actual women at real work with no glory or joy: at homework with children around a table, employed at high-speed machinery, compelled to keep up with the pace on shop floors. They operated dangerous equipment, kept an assembly line moving, sorted fabricated parts, handled table tools, warehoused finished products. Men invariably appeared in superior supervisory or skilled roles. By means of Hine’s camera, an original body of evidence came to light including the employment of a large population of working class female lives.

Real women implicitly with names, personal histories, families, active lives in urban neighborhoods were now embodied in a new graphic language. bjb

- Title: Women and the Trades by Elizabeth Beardsley Butler

- Glass Decorators-Frontispiece

- Body Ironer at Work-p.183

- Bottling Olives-p.41

- Bottling Pickles & Onions.-p.33

- Cellar Stripping Room-Stogy Factory-p.363

- Coil Winding Room-Westinghouse-p.219

- Dangerous Staying Machine-p.261

- Feeder at Cylinder Mangle-p.169

- Filing & Capping Mustard Jars-p.37

- Folders-Job Printing Office-p.279

- Garment Workroom-p.103

- Glass Decorators-p.245

- Glassware-Wash-Clean-Packing-p.239

- Head of the Checkroom-p.191

- Laundry Ironing Room-p.187

- Lunch Room-Stogy Factory-p.311

- Mica Pasting Department-Westinghouse-p.215

- Mold Stogy Rolling-p.85

- Operators at a Mangle-p.173

- Pasting Cigar Boxes-p.257

- Sorters in Sheet-Tinplate Mill-p.227

- Starching by Hand-p.177

- Stripping Tobacco-p.79

- Sweatshop Proprietor-Employees-p.95

- Telephone Exchange-p.287

- Tobacco Strippers-p.97

- Tobacco Stripping in Sweatshop-p.87

- Types of Laundry Workers-p.201

- Women Core Makers-p.211

- Working at Suction Table-p.91

- Working Girls Club-p.325

THE WORKING WOMAN, PHOTO BY HINE (1908-1913)

- The Woman’s Invasion I (1908)

- The Woman’s Invasion II (1908)

- The Immigrant Girl In Chicago (1909)

- The Irregularity of Employment of Women Factory Workers (1909)

- Working-Girls’ Budgets: Self-Supporting Girls (1910)

- Working-Girls’ Budgets: Shirtwaist-Makers and Their Strike (1911)

- Working-Girls’ Budgets: Unskilled and Seasonal Factory Workers (1911)

- Women Laundry Workers in New York (1911)

- Artificial Flower Makers (1913)

- Women In The Bookbinding Trade (1913)

THE CITY, STREET-LAND, PHOTO BY HINE (1909-1915)

- Immigrant Types in the Steel District (1909)

- Homestead: The Households of a Mill Town by Margaret Byington (1910)

- Work-Accidents and The Law by Crystal Eastman (1910)

- The Hired City by James Oppenheim (1910)

- The Old World In The New By Edward Alsworth Ross (1914)

- Street-Land: Its Little People and Big Problems by Philip Davis (1915)

- Street Life: Gambling, Drinking, Amusement Play