CONTENT

- HOME PAGE

- PROLOGUE AN URBAN LEGACY

- INTRODUCING THE WEST SIDE

- 19th-CENTURY CAMERA

- URBAN PHOTOGRAPHERS HINE AND KIRKLAND

- PICTORIAL CHICAGO

- CHICAGO ENLIGHTENED CITY BEAUTIFUL

- CHICAGO GROTESQUE LAWLESS STREETS

- HULL-HOUSE "OASIS" IN A SLUM

- IMMIGRANT EMIGRANT CITY

- "ALIEN" COLONIES

- "RACE" COLONIES

- GHETTO LIVING

- "CHEAP" ECONOMY

- FAMILY

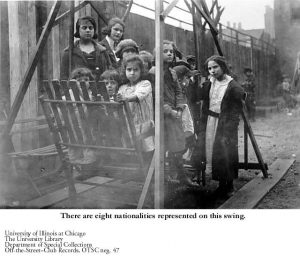

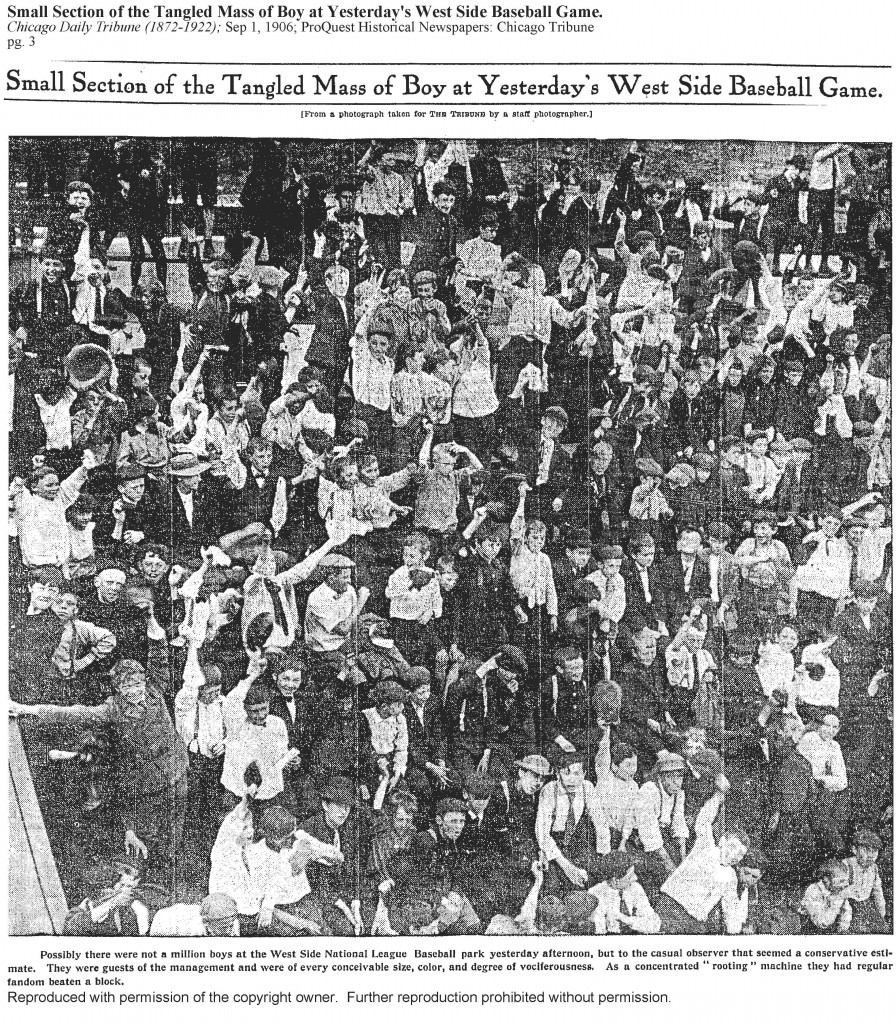

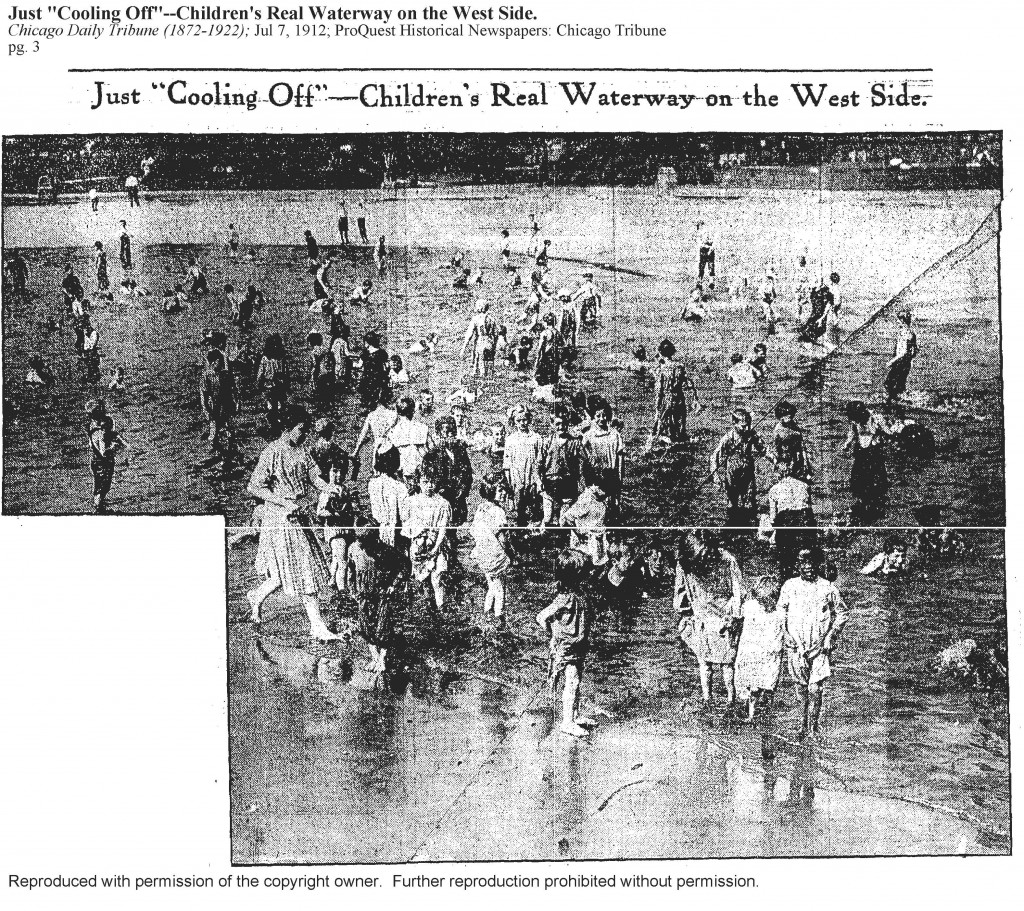

- AMUSEMENTS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- TENEMENTS

- URBAN SOCIOLOGY CHICAGO SCHOOL

- MAXWELL STREET ARCHITECTURE TOUR

- CHICAGO CITY MAPS

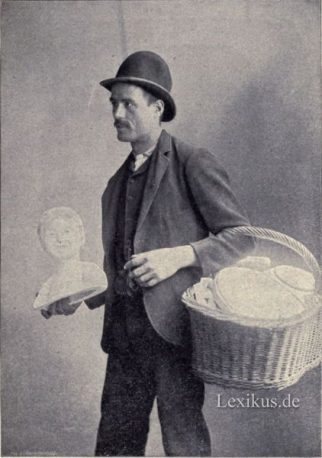

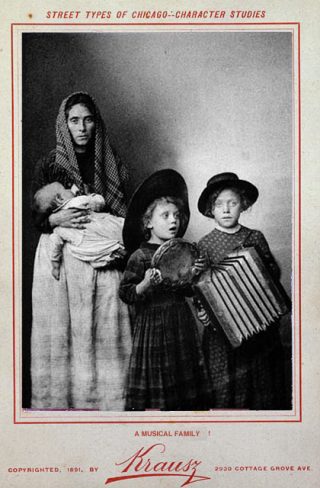

PICTORIAL CHICAGO

VISUALIZING THE FEEL OF CHICAGO A COSMOPOLITAN METROPOLIS

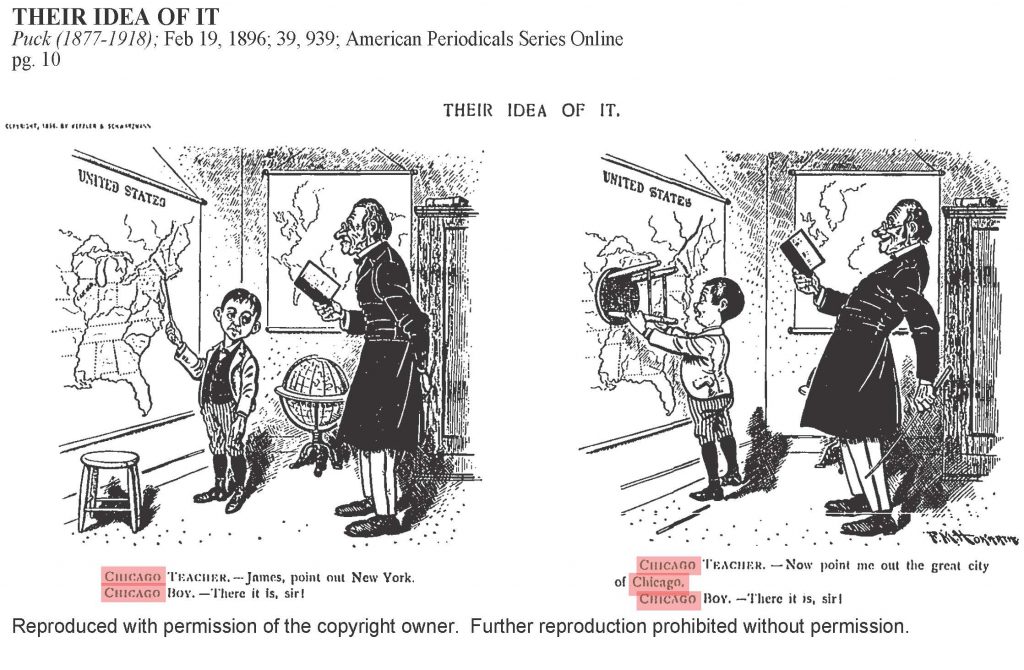

Chicago grew very rapidly in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, one million people by 1890, over two million by 1900. Many who came to the city–foreign immigrants, internal migrants, commercial travelers, tourists, visitors–often viewed the city in pictures before seeing it first-hand. Later many would not recall if they saw a scene first personally with their own eyes or in a photograph.

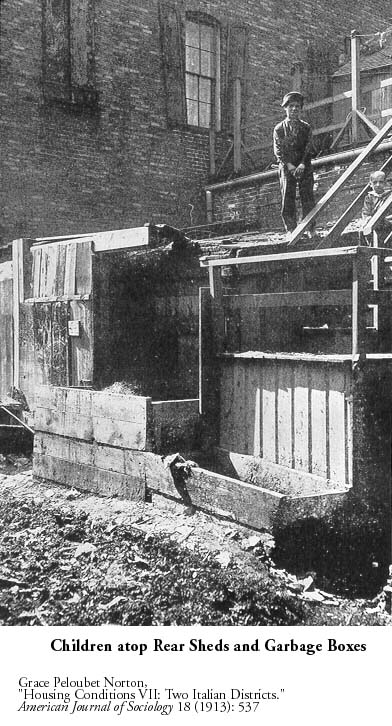

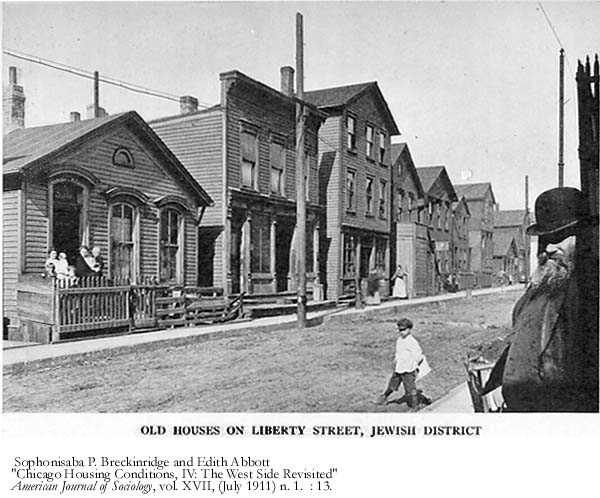

The advent of photography in the 19th century, including use of the inexpensive and portable Kodak in the 1890s and Brownie in 1900, irreversibly changed the powers and importance of the perception of a place. Photographs printed in newspapers and magazines; photographs appearing in guidebooks and on Picture Post Cards–all became familiar items in an expanding visual medium. Chicago’s West Side was especially eye-worthy. The American Journal of Sociology, edited and published in Chicago, was the first and only academic journal in the period to include photographs as a component of knowledge. In high-brow intellectual circles the film image was deeply suspect as unoriginal, unimaginative, sensational, unscientific, and therefore vulgar.

Upsetting their staid convictions, privileged New Englanders admitted to a perverse experience witnessing Chicago in the actual. Visiting the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago a penultimate Boston Brahmin, Henry Adams, was stunned that the city best known for a commitment to business would “lavish millions and millions of money and infinite effort” to produce something that was not business but beauty … the Greeks might have delighted to see and Venice would have envied.” Of all places, that Chicago “should turn on us with this sort of defiant contempt, and fling its millions into our faces, in order to demonstrate to us that we understand neither business nor art, was not to be expected; but I admit the demonstration is complete.”

William James, a “radical empiricist” with a pictorial flair after teaching a summer term at Chicago University in 1903, told his condescending brother Henry , “Great hulking rustics from prairie towns with thick hands, teachers mainly, and tall womankind to match, aged well over 25, all of them, and earnest and absorbent in a way unknown to Harvard.”

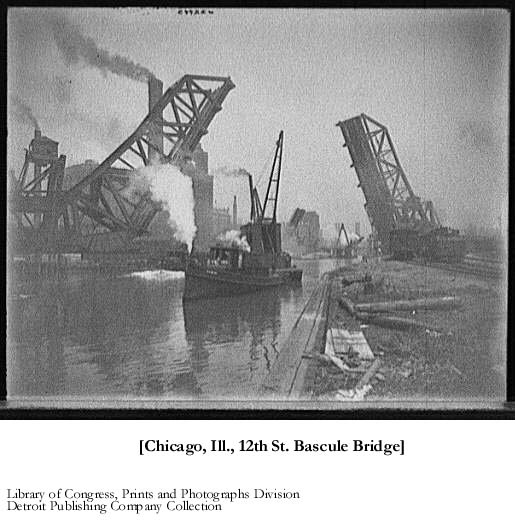

What made Chicago different was the size, complexity, largely unplanned and sudden expansion of the city by orders of magnitude compared to Midwestern towns and Eastern seaboard cities. Space in the Midwestern metropolis was continually shape-shifting along with the surging population. The phenomenon generated a confusion of changing addresses, asymmetrical streets, oblique roads–all transforming an original grid.

Getting through the urban tangle, getting one’s mind around the jumble of people, places, and activities was a commuter’s challenge, then as now. Required to navigate the sections of the city–North, West, South, East–were published aids permitting a traveler to focus attention on plotting directions to and arriving at a specific destination.

Portable manuals with visual instructions embedded in commercial guidebooks, street maps, newspaper directions–all now found receptive audiences for profitable enterprises. The “propriety of renaming the city” was suggested by a letter writer to the Chicago Daily Tribune in August 1880. “Certain towns in Europe are distinguished by their locations on the banks of rivers, as Frankfort-on-the-Main, Newcastle-on-the Tyne …. As an appropriate name … I would suggest that hereafter this place be known as Chicago-on-the-Make.” bjb